FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Within five months, five deaths: my wife, my youngest brother, my longtime agent, my editorial partner on the “Mystery Makers” series, and the secretary without whose gentle mentoring I’d still be batting out words on a manual typewriter. I’ll never remember this year fondly. But before it closes, and before next January 6 when I collide with my 69th birthday, I’d like to begin writing again.

In a column that dates back to before any of those deaths, I mentioned that some of the music Bernard Herrmann wrote for the earliest episodes of the CBS Adventures of Ellery Queen radio series could be seen on the Herrmann Society website. Now it can be heard too. If you go to www.filmscorerundowns.net and then click on “CBS Audio Clips,†you’ll be able to listen to 21 Herrmann excerpts, most of them unavailable elsewhere.

Two of the three earliest come from the 60-minute Ellery Queen episode “The Last Man Club†(June 25, 1939) and the third from “The Impossible Crime†(July 16, 1939), all three performed on a synthesizer by David Ledsam. Even without the original instrumentation, the 31-second Cue 1 from “The Last Man Club†is instantly recognizable as Herrmann, although the other two lack the uniquely ominous sound that he became famous for.

But it’s hauntingly present in the vast majority of these 21 audio clips, and anyone who listens to all of them will perhaps understand why I’ve called Herrmann the Cornell Woolrich of music.

You can listen to dozens more audio excerpts, many from legendary TV series like Perry Mason and Have Gun Will Travel and Gunsmoke, if you visit www.bernardherrmann.org and then click on “Herrmann CBS Legacy.†Both of these centenary tributes to perhaps the greatest of all film composers were prepared and arranged by Herrmann authority Bill Wrobel.

As chance would have it, Herrmann and Queen interfaced again almost a quarter century after the Queen radio show debuted. “Terror in Northfield†(October 11, 1963), one of 17 episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour with original Herrmann scores, was based on a non-series novelet by Queen.

Herrmann’s music for that and eight other episodes of the series is available on three CDs in the recently released Varese Sarabande set The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, Volume Two, which I recommend highly.

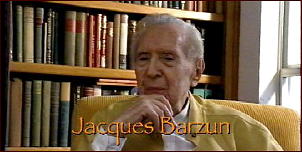

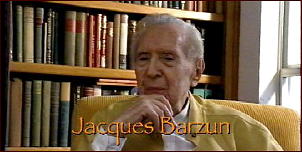

November 30 of this year marked the 104th birthday of the world-renowned historian of ideas Jacques Barzun, who in the early 1920s was a classmate of Woolrich at Columbia University and to whom we owe everything that is known about the young manhood of the Hitchcock of the written word.

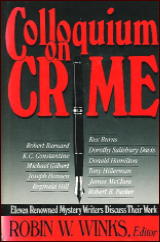

My first contact with Barzun was in the late Sixties when I arranged for his essay “Detection and the Literary Art†to be reprinted in my anthology The Mystery Writer’s Art.

We met in 1970 when I was living in New Jersey and working on the Woolrich collection Nightwebs. Barzun invited me to his office in Columbia’s Low Library and spent the better part of an afternoon describing for me what the university was like in the years immediately after World War I and also, of course, what the young Woolrich was like.

The factor that seems to have brought the two together was that they were the only members of their class who had spent most of their lives outside the United States, Barzun in France and Woolrich in Mexico with his father.

Their friendship came to an end when Woolrich sold his first novel to a major publisher while in junior year and quit Columbia under the delusion that he was about to become the next F. Scott Fitzgerald. He wound up one of the founders and the supreme practitioner of the dark suspense genre we now call noir.

Woolrich’s brand of desperate anguish was not Barzun’s cup of tea. His mammoth Catalogue of Crime (2nd ed. 1989) makes it clear that he much preferred humdrum English authors like John Rhode.

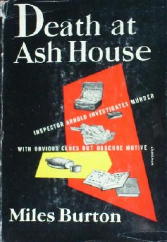

I had read some Rhode and also another humdrum Brit signing himself Miles Burton, and had noticed something very strange about both sets of books. Whenever a character asks a question of another, the verb following the second character’s line of dialogue is always the same. Always.

Hundreds of times in each book, hundreds of thousands of times in the complete works. “ABC?†asked Inspector Boothbridge. “XYZ,†Lord Wychthorpe replied. “One two three?†Dr. Coxcroft inquired. “Eight nine ten,†Mrs. Hornbeam replied.

The obvious conclusion is that Rhode and Burton were the same man, but apparently no one had mentioned it before me (in The Armchair Detective for October 1968). At any rate Barzun in Catalogue of Crime credited me with the discovery.

Among those who weren’t aware of the Rhode-Burton identity was Anthony Boucher. He thought most of the Rhode books dull but usually reviewed them soberly, while the Burton novels he ridiculed and detested. Here’s his complete review of Death at Ash House from the San Francisco Chronicle for December 6, 1942:

“Inspector Arnold plods through the problem of the bashed secretary and at last catches up with the reader. Relentlessly painstaking — and giving.â€

Here’s what he had to say about Accidents Do Happen in the Chronicle for February 10, 1946:

“A famous editor [I suspect he means Simon & Schuster’s Lee Wright] once said, ‘No American mystery can be so dull as a dull British, and no British as bad as a bad American.’ Mr. Burton gives her the lie. Not only is his latest dull, endless and snobbish; its ending (one can hardly say solution) provides the most incompetent detecting … of the past decade — bad enough to make the brashest American quickie seem well plotted.â€

These and three more snarky reviews of Burton can be found in The Anthony Boucher Chronicles (2001). Burton’s American publisher dropped him before Boucher took over as mystery critic of the New York Times but they continued to appear in England until 1960.

The Rhodes kept coming out on both sides of the Atlantic and Boucher reviewed all of them, perhaps because as a Catholic he thought he should do penance for his sins. I remember he called one of them “the dreariest Rhode I have yet traversed.†I can’t recall anything about the book of which he said it.