Unlocking the Mystery of the Hard-Boiled Heart:

Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key

A Review by Curt J. Evans

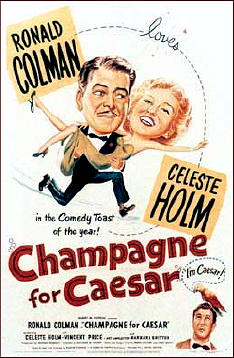

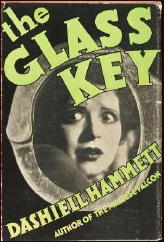

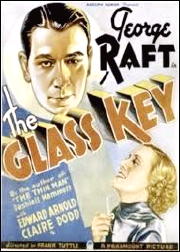

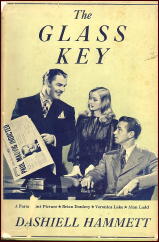

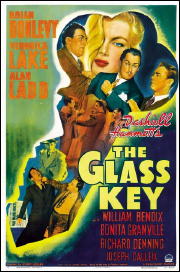

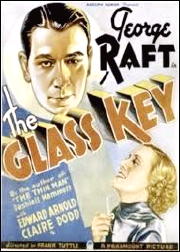

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Glass Key. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1931. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and soft. Film: Paramount, 1935 (George Raft, Edward Arnold, Claire Dodd); also: Paramount, 1942 (Alan Ladd, Brian Donlevy, Veronica Lake).

Having complained in an earlier article here on Mystery*File about the lack of analysis of Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key in Leonard Cassuto’s Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, I thought I would test the novel along the thematic lines suggested by Cassuto’s book. How “sentimental†is this landmark of hard-boiled crime fiction?

Cassuto’s omission of a discussion of The Glass Key is a notable one. Many eminent crime novel critics, such as Julian Symons and Tom Nolan, consider The Glass Key to be Dashiell Hammett’s greatest masterpiece, even more significant than The Maltese Falcon.

“The Glass Key is the peak of Hammett’s achievement, which is to say the peak of the crime writer’s art in the twentieth century,†declared Symons in his classic genre survey, Bloody Murder, in 1972. The Glass Key “stands out as arguably [Hammett’s] masterpiece and certainly as one of the high points of American crime fiction,†echoed Tom Nolan nearly thirty-five years later (Wall Street Journal, 15-16 April 2006, p.16).

The Glass Key probably is my favorite among Hammett’s novels, though I admit that I prefer the novels of Raymond Chandler (though conversely I prefer Hammett’s short stories to Chandler’s). Admittedly, Hammett’s narrative style, with its relentless focus on externals, is a notable achievement. Here is a representative passage, detailing the actions of Hammett’s “fixer†protagonist, Ned Beaumont:

He put the cigar on the edge of the table with nervous fingers. He put the messages away once more and leaned back in his chair, staring at the ceiling and biting a fingernail. He ran fingers through his hair. He put the end of a finger between his collar and his neck. He sat up and took the envelopes out of his pocket again, but put them back without having looked at them. He chewed his lower lip. Finally he shook himself impatiently and began to read the rest of his mail. He was reading it when the telephone bell rang.

Some writers might have written, “Ned Beaumont showed signs of agitation,†and left it at that. Not Hammett! He shows you those signs of agitation; he tells you all about them. If you want know what is going on in Beaumont’s brain, however, you must go solely by those very external physical manifestations; this is all Hammett provides you.

It is an impressively maintained narrative style, but I personally prefer Chandler’s narrations, where his detective-knight tells everything he is thinking (or, at least, all he is aware that he is thinking).

As Mike Nevins has noted in 1001 Midnights, given Hammett’s emotionally opaque narrative style, the reader faces a greater challenge interpreting motivations, not merely of supporting characters, but of the enigmatic central figure, Ned Beaumont.

I trust most people know the basic story of The Glass Key. Paul Madvig, an urban political boss, has thrown in his lot with the aristocratic Henry family. This family consists of the father, a senator (whose political campaign Madvig is backing), the lovely daughter, Janet (with whom Madvig is deeply enamored) and the simply stinkeroo son, Taylor (a decadent who evidently is debauching Madvig’s daughter Opal).

Beaumont, Madvig’s rather brighter friend and his right-hand (left-hand?) man, warns Madvig that involvement with the Henrys will just lead to trouble: “That’s why I’m warning you to sew your shirt on when you go to see them, or you’ll come away without it, because to them you’re a lower form of animal life and none of the rules apply.†(This is a beautifully written sentence, by the way. I hope it was used in the film adaptations.)

When Taylor Henry is found — by Beaumont — dead in the street, a victim of violence, a net gradually starts tightening around Madvig, as he seems increasingly implicated in the dread deed and political opponents are striving to take advantage of his vulnerability (those copious anonymous letters accusing him of murder do not help). Beaumont sticks his nose in, for reasons of practicality, personal honor and friendship.

One of the suspects in the Taylor Henry murder is a bookie named Despain, who has welched on a big payoff owed to Beaumont. So admittedly there is a practical pecuniary reason for Beaumont involving himself in the affair. But there is more to it than that, as Ned himself states to Madvig:

“Do you expect me to stumble over corpses without batting an eye?…But forget that. That doesn’t count now. This does. I’ve got to get this guy. I’ve got to.. .Listen, Paul, it’s not only the money, though thirty-two hundred is a lot, but it would be the same if it was five bucks. I go two months without winning a bet and that gets me down. What good am I if my luck’s down? Then I cop, or think I do, and I’m all right again. I can take my tail out from my legs and feel that I’m a person again and not just something that’s being kicked around. The money’s important enough, but it’s not the real thing. It’s what losing and losing and losing does to me… And then, when I think I’ve worn out the jinx, this guy takes a Mickey Finn on me. If I stand for it I’m licked, my nerves gone. I’m not going to stand for it. I’m going after him.â€

We are on a pretty spiritual level here! It is not mere money that is at stake here, then, but Beaumont’s basic worth as man.

As Madvig himself is threatened by conspiracy and circumstance, Beaumont’s motivation for playing “amateur detective†(as he himself puts it) comes to revolve around his personal friendship with Madvig. “You’re right about my being Paul’s friend,†Ned tells Janet Henry, “I’m that no matter who he killed.â€

And, sure enough, Ned memorably proves his devoted friendship throughout the novel. (He also proves the truth of his credo, “I can stand anything I’ve got to stand†— Ned has to “stand†quite a lot, including cruelly prolonged beatings.)

And here we find “sentimentality†and “empathy†in this violent hard-boiled tale filled with unpleasant people (along with Beaumont’s prolonged beatings/torture, the manual strangulation and neck breaking of another character and a ruthless psychologically induced suicide).

Raymond Chandler called The Glass Key “the record of a man’s devotion to a friend,†while critic James Sandoe observed that the novel “is quite as much an exceptionally delicate scrutiny of friendship under curious conditions as it is a detective story.â€

Throughout the novel, Beaumont suffers greatly to help his friend Madvig (ironically, one of the things he suffers is the potential loss of his friendship with Madvig). To be sure, this is “sentimentality,†but it is of the “male bonding†(or, to use modern lingo, “bromanceâ€) sort so familiar from Chandler.

So, how do the ladies fare in The Glass Key? Pretty fair, actually!

I think we also see in the novel some of the engagement with feminine domestic sentimentality that Cassuto discusses in his book. Madvig has his own household, which includes his presumably widowed mother and his daughter Opal. Ned clearly is a part of this household as well — he effectively is a sort of adopted relation — and he is attracted by the psychic comforts it offers (he calls Opal “Snip†and Mrs. Madvig “Momâ€). So his empathy extends beyond his friend Paul to Paul’s womenfolk.

There is also the important matter of the Henry household and the fascinating character of Janet Henry (did Veronica Lake do justice to her?). Janet has a complex role in The Glass Key, combining the functions of destroying femme fatale and nurturing good girl in her one lovely self. Her relationship with Ned is left ambiguous (in my eyes) up to the last line of the novel. Such dialogue the two characters share as

“You despise me… You think I’m a whore.â€

“I don’t despise you… Whatever you’ve done you’ve paid for and been paid for and that goes for all the rest of us.â€

is not exactly the quintessence of sentimental lovers’ romance. (I cannot imagine that these sentences are uttered by Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.) Yet clearly some sort of more sympathetic relationship between the two develops over the course of the novel.

Does the ending — foretold by Janet’s vivid nightmare of herself, Ned, the glass key and the house full of snakes — signify, as literary critic Stephen Knight contends, the withdrawal of a “semi-criminal but ultimately heroic figure [Beaumont]…from crime [Madvig] into tentative romance [Janet]â€? Hammett deliberately leaves us hanging.

Some critics have argued that Ned’s real love relationship in The Glass Key is not with Janet but rather with his great friend Paul, i.e., that Beaumont has latent homosexual feelings for Madvig. The ambiguous last line of the novel could be read as supporting that reading, as could this frustratingly uncompleted query from Madvig to Beaumont during the two men’s climactic argument:

“What is it, Ned? Do you want her yourself, or is it–†He broke off contemptuously. “It doesn’t make any difference.†He jerked a thumb carelessly at the door. “Get out, you heel, this is the kiss-off.â€

Was Madvig going to accuse Beaumont of harboring “unnatural†feelings for him? Would his question, completed, have been something like, “Do you want her yourself or is it that you’re jealous of her?â€

Do we have an unusual love triangle here? Or are such questions — which come up concerning Chandler’s work as well — merely reflective of modern-day sociocultural perceptions, imposed on writing of the past? I do not have the definitive answer — I do not see how there can be one — but I do love this exchange between Beaumont and Madvig:

Ned Beaumont nodded. He was looking at the blond man’s outstretched crossed ankles. He said: “You oughtn’t to wear silk socks with tweeds.â€

Madvig raised a leg straight out to look at the ankle. “No? I like the feel of silk.â€

“Then lay off tweeds. Taylor Henry buried?â€

Class commentary (Madvig is a parvenu who does not fit in with his new aristocratic circle) or homosexual subtext? Let the reader decide!

However, whatever the exact nature of Ned’s and Paul’s relationship, male camaraderie and honor among men undeniably are key concerns of The Glass Key, as is true of many of the Chandler novels, which also have been assiduously mined for gay subtext.

(I am not even addressing the matter of the sadistic, apish bruiser Jeff, who seems to get an erotic thrill out of beating Ned — a phenomenon much commented on by film critics in relation to the 1942 film adaptation of The Glass Key, which starred diminutive pretty boy Alan Ladd as Ned and hulking William Bendix as a memorably twisted Jeff).

As my comment above demonstrates, The Glass Key also can be (and has been) analyzed for its attitudes about American class and social structure. Hammett makes his own distaste for “the aristocracy†manifest throughout the novel and one could attribute much of Ned Beaumont’s attitudes and actions to this. Indeed, the solution to the mystery in my view is predictable to anyone sufficiently familiar with Hammett’s political beliefs.

For me, the theme of this novel can best be summed up as the struggle of a man to behave with a semblance of honor in a grievously corrupted world (see those snakes in Janet Henry’s glass key dream). Attitudes about domestic sentimentality are an aspect of this novel, but not the central concern. To be sure, however, there is much that can be debated.

The Glass Key has been praised as Hammett’s best formal mystery novel and it may well be that; but I think the mechanics of the puzzle itself really are of comparatively minor interest.

Tellingly, in a typical detective novel of the period the “glass key†of the title would refer to an actual physical object (perhaps a key used to gain entrance to Taylor Henry’s and Opal Madvig’s assignation place); but in Hammett’s tale, this key is a metaphorical symbol.

Yes, there is some discussion about a hat and a walking stick and anonymous letters and a typewriter and Beaumont in his role of amateur detective makes some whopping big intuitions about the behavior of a couple of people; yet most of the story’s interest in my view lies in its tough tone, its urban realism and, most of all, its allusive characters.

In short, the really fascinating mystery in The Glass Key is less the matter of whodunit than it is just what makes this group of fallen people tick.