The Murder of Mystery Genre History:

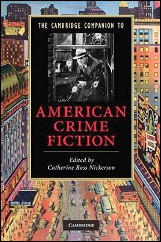

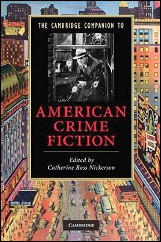

A Review of The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction

by Curt J. Evans

On the back cover of The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction (Cambridge University Press, 2010; Catherine Ross Nickerson, editor), the blurb tells us that the fourteen essays contained therein represent the “very best in contemporary scholarship.” If so, this should be a matter of grave concern to people interested in the history of the American mystery genre before World War Two.

As the Companion is a skimpy book of less than 200 pages and it has fourteen essays, potential readers should be immediately clued in to the fact that the essays tend to be rather cursory. A listing of the essays further reveals that the book’s coverage is esoteric, leaving noticeable gaps:

Introduction (4 pages)

Early American Crime Writing (10 pages, excluding footnotes)

Poe and the Origins of Detective Fiction (8 pages)

Women Writers Before 1960 (12 pages)

The Hard-Boiled Novel (15 pages)

American Roman Noir (12 pages)

Teenage Detective and Teenage Delinquents (13 pages)

American Spy Fiction (9 pages)

The Police Procedural on Literature and on Television (13 pages)

Mafia Stories and the American Gangster (10 pages)

True Crime (12 pages)

Race and American Crime Fiction (12 pages)

Feminist Crime Fiction (14 pages)

Crime in Postmodernist Fiction (12 pages)

Further evidence of highly selective coverage can be found in the “American Crime Fiction Chronology” at the beginning of the book. Here are its milestones in crime fiction from 1841 to 1939:

1841 Edgar Allan Poe, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”

1866 Metta Fuller Victor,

The Dead Letter

1878 Anna Katharine Green,

The Leavenworth Case

1908 Mary Roberts Rinehart,

The Circular Staircase

1923 Carroll John Daly, “Three Gun Terry”

1925 Earl Derr Biggers,

The House Without a Key

1927 S. S. Van Dine,

The Benson Murder Case

1927 Franklin Dixon,

The Tower Treasure

1929 Dashiell Hammett,

Red Harvest

1929 Mignon Eberhart,

The Patient in Room 18

1930 Carolyn Keene,

The Secret of the Old Clock

1934 James M. Cain,

The Postman Always Rings Twice

1934 Leslie Ford,

The Strangled Witness

1938 Mabel Seeley,

The Listening House

1939 Raymond Chandler,

The Big Sleep A pretty obvious pattern can be constructed from these fifteen fictional milestones:

The Distant Founder: Poe

The Women: Victor, Green, Rinehart, Eberhart, Ford, Seeley

The Hardboiled Men: Daly, Hammett, Cain, Chandler

The Non-hardboiled Men: Biggers, Van Dine

The Children’s Authors: “Dixon” and “Keene”

One would conclude from this list that American men donated practically nothing to the detective fiction genre after 1841 (Poe), outside of the hardboiled variant and juvenile mystery (the authors of the Hardy Boys tales). Apparently the only significant male producers in the nearly 100 years between Poe’s first story and Chandler’s first novel were the creators of Philo Vance and Charlie Chan.

But it gets even worse when we look at the actual text. S. S. Van Dine gets four mentions, all cursory, some problematic:

On page 1 his rules for writing detective fiction are mentioned, dismissively.

On page 29, he is dismissed as an imitator of Agatha Christie.

On page 43, he is called an imitator of Arthur Conan Doyle and used as the usual hardboiled punching bag for not writing about “reality” (though he interestingly is deemed “the era’s most popular writer”).

On page 136, it is claimed that The Benson Murder Case is “widely acknowledged as the first American clue-puzzle mystery”

Earl Derr Biggers gets one line, solely for having created an ethnic detective (see “Race and American Crime Fiction”).

At least these non-hardboiled make writers are mentioned! The hugely popular and admired genre author Rex Stout is another lucky lad. Though he missed the list of milestones, Stout nevertheless in mentioned in the text:

On page 47 he is noted for having merged hardboiled and classic styles.

On page 136, he is criticized, along with Van Dine, for ignoring race and gesturing “more toward Europe than actual American cities” and writing about rich white bankers, stockbrokers and attorneys (yup, “Race and American Crime Fiction” again).

On the other hand, if you are looking for anything on Melville Davisson Post, Arthur B. Reeve or Ellery Queen, forget it! They did not exist apparently; we only imagined them all these years.

Meanwhile, Anna Katharine Green gets two pages, Mary Roberts Rinehart three and Mignon Eberhart, Leslie Ford and Mabel Seeley together as a trio another two. (Heck, even the lovably loopy Carolyn Wells gets a line in this book.)

The editor of the Companion, Catherine Ross Nickerson (author of The Web of Iniquity — a book, you may not be surprised to learn, about Anna Katharine Green and Mary Roberts Rinehart — and, in the Companion, of “Women Writers Before 1960â€) lectures in her Introduction that:

“It is only fairly recently that the multiple genres of crime writing have been taken up as subjects of academic study; before that, they were entirely in the hands of connoisseurs and collectors, with their endless taxonomies, lists and value judgments. What Chandler opened up was a new way of looking at crime narratives, or rather looking through them, as lenses on the culture and history of the United States.”

This is an interesting idea indeed, but unfortunately Professor Nickerson’s own selective coverage gives us an inaccurate view of the genre and, thereby, surely, of American cultural history.

According to Nickerson, there were two indigenous creative strains in American mystery: the female domestic novel/female Gothic (the Brontes and Mary Elizabeth Braddon are admitted as influences here but not Wilkie Collins or Sheridan Le Fanu); and the hardboiled.

It seems that despite the existence of Poe, what we think of as the Golden Age detective novel was an artificially transplanted English import, about as American as scones and crumpets. Nickerson dismissively notes these “Golden Age” works for their “tightly woven puzzles and country houses full of amusing guests” and declares that they were “presided over by Agatha Christie and imitated by Americans like S. S. Van Dine.”

So if you were an American male writing mysteries that emphasized puzzles and had upper middle class/wealthy milieus, you were part of a British tradition and thus not worthy of inclusion in a historical survey of American mystery fiction. But if you were an American woman writing mysteries with puzzles and upper middle class/wealthy milieus, you were part of the American female domestic novel/Female Gothic tradition (even though some of this tradition is British and male) and you make it into the genre survey.

Make sense to you? It doesn’t to me. Personally I think Professor Nickerson should take another look at those “connoisseurs and collectors, with their endless taxonomies, lists and value judgments” who she dismisses so casually. There are still things that an academic scholar writing about the mystery genre can learn from them.

Granted, they often were men who tended to be overly dismissive of women’s mystery fiction — or at least the suspense strain in it that they mockingly termed “HIBK” (Had I But Known) — but writing important men out of the history of the genre is no way to redress the balance.

Crime literature may be about violence, but scholars of crime literature should not practice “an eye for an eye.” Doing so does not make for good scholarship.