Sun 19 Dec 2010

Reviewed by J. F. Norris: CHARLES FELIX – The Notting Hill Mystery.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[8] Comments

CHARLES FELIX – The Notting Hill Mystery. Bibliographic information included in the essay that follows.

I have had a book hanging around my home for about the past five years, and I vaguely recall moving it around from box to box for some time. It is an anthology with the rather bland title of Novels of Mystery of the Victorian Age (Pilot Press, UK, 1945; Duell Sloane & Pearce, US, 1946) and weighs in at a hefty 800+ pages.

Only last month did I finally open the thing. The title hinted at what I hoped would be a book of forgotten tidbits that I would keep me busy reading for a few weeks, but a quick scan of the Table of Contents told me why I left it untouched in a box for so long. Of the four “novels” listed only one really qualified as such and the other three were more novellas.

Three of the titles were extremely familiar and (in my opinion) not worthy of inclusion as they have remained in print since their initial publication. Those long lasting works are: The Woman in White, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde and Carmilla.

The fourth title, however, gave me the reason as to why I hung onto the book. That title is The Notting Hill Mystery — a book I remember coming across in a list of noteworthy detective novels reissued back in 1976 by Arno Press as its first US edition, and even so a rather scarce book in the antiquarian trade.

A quick flip through A Catalogue of Crime shows that Jacques Barzun also came across the novel in the same anthology and wrote a laudatory one paragraph blurb. Maurice Richardson’s introduction to the story in Novels of Mystery was like a really good movie trailer — it piqued my interest enough without giving too much away, and I decided then and there to read the thing at long last.

Well, I was utterly surprised by what I found in the pages. It turned out to be a detective novel and a true mystery and much to my delight included the perfect blending of the cerebral and the bizarre. It was — to be blunt — right up my alley!

First a prelude about the author. In this anthology the author is listed as it was in the book’s original published format, as a magazine serial, when its author was “by Anonymous.” [Once a Week: An Illustrated Miscelleny of Literature, Art, Science & Popular Information, circa 1862-1863.]

Since then there has been some scholarly research to determine that the first book format of The Notting Hill Mystery (London: Saunders, Otley, 1865) changes Anonymous to “Compiled by Charles Felix from the papers of the late R. Henderson, Esq.”.

Richardson makes brief mention of Felix in the introduction to the novel and that at the time little else had been uncovered about Felix. That could be because Charles Felix is clearly a pseudonym, since the “papers” and “R. Henderson ” are all fictional.

Hubin lists only three books attributed to Felix. I have been unable to locate any of the other titles. Certainly I’d be interested to see if he was as innovative in the other stories as he is in The Notting Hill Mystery.

[ *** PLOT ALERT *** The remainder of this essay, more than a mere review, may reveal to the discerning reader more details of the plot than you may wish to know. ]

I also learned why Richardson chose to place it in the same volume with Collins’ masterful sensation thriller. It is definitely influenced by The Woman in White, with which it shares the basic plot of a sinister husband attempting to win his wife’s fortune by criminal means.

The title is, however, somewhat of a misnomer. It should more accurately be called The Notting Hill Mysteries for it presents the reader with no fewer than four genuine mysteries and three mysterious deaths.

◠Mystery #1 – What happened to the kidnapped sister?

◠Mystery #2 – How can a woman be poisoned yet no trace of poison remain in her body?

◠Mystery #3 – What can drive a clearly innocent person to commit suicide prior to a murder trial?

◠Mystery #4 – When is murder not really murder? Or this corollary – can murder be committed and yet not ever be classified as such?

The typically involved Victorian plot tells us straight off that a woman has died what follows is an investigation into her questionable accidental death. The culprit’s identity is hinted at the onset.

This may lead the reader to think that story will be something of the inverted variety so masterfully executed in later years by R. Austin Freeman and Francis Iles. Make no mistake — the book indeed will develop into a detective novel of the fair play variety (perhaps teetering on the brink of “fair play” as we know it).

Our narrator begins with the tale of a woman who gave birth to twin girls then died shortly thereafter. We are told that the two girls though not identical in appearance are nonetheless almost of one mind — “in effect psychically linked.”

One girl often managed to feel things that the other was experiencing and vice versa. We follow the story of one of those daughters (Gertrude Bolton) while the other (Catherine Bolton) we eventually learn is abducted by gypsies. Gertrude was a sickly child all her life, and when she marries William Anderton he tries to cure her chronic illnesses. He tries all sorts of remedies and this leads him to experiment with the latest trend -– mesmerism.

Then we are introduced to Baron R** and his assistant Madame R**. Madame R** we learn through various means is actually Charlotte Brown, a former tightrope walker with a traveling circus, who later changed her name to Rosalie when she joined the Baron after he discovered she had clairvoyant powers. [FOOTNOTE]

Perhaps I should mention now that the story takes the form of an epistolary novel with a central narrative written by an insurance investigator who submits supporting documents made up of various sworn testimonies, and letters that further explain the mystery surrounding the multiple deaths.

At this early stage, the reader is presented with mystery number one – what happened to Catherine Bolton, the girl abducted by the gypsies? It is fairly easy to solve although it is not officially announced until much later in the story.

Mystery number two is revealed in the relationship between Madame R** and Gertrude Anderton. Here is the first truly weird or supernatural element: Madame R**/Rosalie’s clairvoyant powers seem to be more of a paranormal empathic relationship with Gertrude, for they feel the same things both emotionally and physically.

Rosalie manages to take on Gertrude’s illness and heal her. Similarly Gertrude begins to feel things that affect Rosalie. And the main plot of the story uses this supernatural aspect to reveal to us that Gertrude is feeling the effects of a slow poisoning that really is being experienced by Rosalie. (Have you perhaps solved mystery #1?)

Then the story shifts focus to the diabolical Baron and how he cares for his now ailing wife Madame R** (aka Charlotte Brown, aka Rosalie, aka you’ve probably guessed.). Along the way circumstances lead the police to fingering Gertrude’s husband as the prime suspect, and that too will lead to tragedy.

There is also the slow reveal of a plot a bit similar to that crafted by Sir Percival in The Woman in White. How the Baron manages to concoct his devilish scheme and carry it out to its terrible conclusion is something one might expect in a modern crime novel than in a story of the Victorian era.

To a modern reader The Notting Hill Mystery may be filled with Victorian contrivances, coincidences and a dash of far-fetched fantasy. I always discount and wholly ignore these picayune criticisms of Victorian era novels. Contemporary readers tend to deny that coincidence has no place in modern literature, when in fact real life abounds with coincidence.

And all fiction is in effect fantasy, therefore I’m always willing to allow for the far-fetched no matter what the genre. Keep in mind that this story was originally published serially in 1862 only a few years after The Woman in White (1860) but earlier than The Moonstone (1868) and decades before books more well known with similar plots.

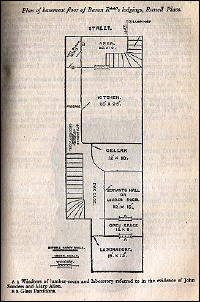

I find the story to be filled with originality –- a brilliant spin on a familiar theme. It must have seemed very new to readers in 1863. Although the epistolary format was common for narrative stories at the time, certainly turning the story into a dossier of sorts with illustrations like floor plans and facsimiles of a letters and marriage certificate was an original idea. Even the means by which each murder is committed (including one which can only be classified as supernatural) are ingenious for genre fiction at the time.

There are quite a few surprises that pile up as the final documents in the case are presented. Perhaps the most stunning surprise comes when the insurance investigator in his summation of the entire sinister affair presents us with Mystery #4 mentioned above and leaves it up to his readers to come to their own conclusion.

FOOTNOTE: The characters really are named Baron R** and Madame R**. That’s not a typo or some Internet glitch. That’s how the names appear in the text throughout the story.

FELIX, CHARLES. Pseudonym of John Retcliff.

-Velvet Lawn (n.) Saunders 1864.

The Notting Hill Mystery (n.) Saunders 1865.

-Ram Dass (n.) Tinsley 1875.

— From the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

[UPDATE] 12-20-10. Jamie Sturgeon emailed me this morning to point out that in Part 38 of the Addenda to the Revised CFIV, Al Hubin has removed John Retcliff as the man behind the Charles Felix pseudonym.

I asked Al for further details, if he had them. Here’s his reply:

“If you google “Charles Felix” “and “John Retcliff” you’ll come across a book dealer’s offering of “Once a Week” by Felix. There’s a long discussion of authorship, and it turns out John Retcliff was a made-up name by Herman(n) Goedsche, 1815-1878, a Prussian secret agent. It’s not clear to me that Goedsche wrote the Felix title, though folks seem to imply that he did. I’ve seen a list of Goesche/Retcliff(e)’s writings, which did not include the Felix titles. So, for me, the authorship of the Felix material is still up in the air.”

Jamie also sent me a copy of Julian Symons’ article in the The Times in which he discusses The Notting Hill Mystery and its place in the history of the early detective novel. It doesn’t appear to be online, but if you’re interested perhaps I can forward the article on to you. Email me offlist, if you would.