Sun 28 Nov 2010

A TV Series Review by Michael Shonk: REMINGTON STEELE, Season One.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[9] Comments

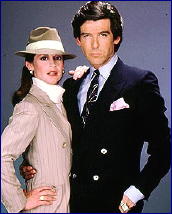

REMINGTON STEELE. Season One: NBC, 1982-83. Created by Robert Butler and Michael Gleason. Cast: Laura Holt: Stephanie Zimbalist, Remington Steele: Pierce Brosnan, Murphy Michaels: James Read, Bernice Foxe: Janet DeMay.

This endearing but lightweight series was at its best in Season One in every way but ratings.

The premise of a female PI creating a fictional male boss so people would accept her as a PI was a timely one. While female PI’s had existed for a long time, even mystery readers were then adjusting to the new independent female PI such as Kinsey Milhone (Sue Grafton) and V.I. Warshawski (Sara Paretsky).

Remington Steele, named for a typewriter (yes, it was that long ago) and a football team, was originally meant to remain fictional. NBC insisted the part be cast, and a romantic comedy mystery with the roles reversed developed.

Writing for the series was at its best during the first season. Experienced showrunner Michael Gleason lead a staff destined to create their own series. Joel Steiger (Jake & the Fatman) won the Edgar award for Best Episode in a TV series for “In the Steele of the Night”. Other writers included Glen Gordon Caron (Moonlighting) and Lee David Zlotoff (MacGyver).

The characters were never more believable. Why wouldn’t a con man and a thief (think Cary Grant in It Takes A Thief) give up that life to have fun chasing Laura and accidentally catching bad guys?

Laura’s reaction to the mystery man was what many young women were going through in 1982 as they chose between a career and marriage. Bernice the secretary meant there was someone in the office to deal with clients while everyone else was off solving mysteries. (This would not be true in coming seasons.)

The acting from stars Stephanie Zimbalist and Pierce Brosnan to the guest stars was of the high quality one expected from an MTM Production (Hill Street Blues, St. Elsewhere, etc).

The relationship between Laura and Remington usually featured them battling each other to see who solved the mystery first. Whatever chemistry between the two worked best during this season.

This was the season I developed a crush on Laura Holt, identified with Remington Steele, enjoyed the comedy mysteries, and saw the potential for another special TV series from MTM Productions. While next season’s move from Friday to Tuesday and NBC wanting more slapstick action made the series a hit, it was at the cost of much of what made Remington Steele special during season one.

Oh, if you decide to view an episode of Remington Steele, watch for the MTM kitty salute to a famous detective at the end.