REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

H. C. BAILEY —

â— Mr. Fortune Objects. Victor Gollancz, UK, hardcover, 1935. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1935.

â— Clue for Mr. Fortune. Victor Gollancz, UK, hardcover, 1936. Doubleday Crime Club, US, 1936, as A Clue for Mr. Fortune. Paperback reprint: Pony Book #52, US, 1946.

Despite his one-time prominence during the Golden Age of the detective story, H. C. Bailey is not that well-known today, outside the community of knowledgeable collectors. Bailey’s tales of the brilliant deductive deeds of his two series detectives, doctor Reggie Fortune and lawyer Joshua Clunk, frequently are first-rate, however.

Clunk appeared only in novels, Fortune in both short stories and novels. Both then and now, the Reggie Fortune short stories probably were/are Bailey’s most highly regarded achievement in mystery fiction.

Indeed, Bailey’s American publishers, Doubleday, Doran, confidently (if somewhat inaccurately, as things turned out) declared in 1936: “Few critics or readers will dispute the fact that of living mystery story writers Bailey is one of those most likely to achieve immortality…and few will deny that Reggie Fortune is his greatest creation.”

There are, I believe, 85 Reggie Fortune short stories, published between 1920 and 1940 — an impressive body of work. If not quite on the level with the Father Brown stories of G. K. Chesterton, they certainly rank high among mystery short stories and are deserving of some sort of reprinting, certainly at the very least a “best of” volume.

Here I review two strong Reggie Fortune collections from the mid-1930s, Mr. Fortune Objects (1935) and A Clue for Mr. Fortune (1936).

One of the best Reggie Fortune collections of short fiction is one of the rarest of them all, Mr. Fortune Objects. This volume contains six long stories: “The Broken Toad,” “The Angel’s Eye,” “The Little Finger,” “The Three Bears,” “The Long Dinner” and “The Yellow Slugs.” All are good tales, while three — “Toad,” “Dinner” and “Slugs” — are among Bailey’s very best short works.

In his day as well as today, the detractors of Reggie Fortune (who included Julian Symons) deemed him a tiresome, precious creation. Reggie’s mannerisms, of which the author often makes a great deal, can be tiring. His speech is telegraphic (like Charlie Chan, who is sparing of pronouns, Reggie is sparing of verbs), affected and arch, he moans and mumbles, and he spends much time fussing over Darius, his blue Persian cat, and his elaborate luncheon and dinner menus. All this is granted.

Yet Reggie also is a legitimate Great Detective, filled with a fervor, quite remarkable for the period, for justice. This moral fervor comes through strongly in Mr. Fortune Objects, in tales that deal in a mature, thoughtful way with the existence of evil in the world.

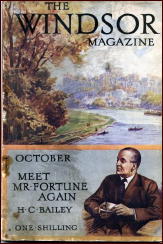

In “The Broken Toad” (a brilliant title for a story that first appeared in the October 1934 issue of Windsor Magazine), the arsenic poisoning of a policeman leads Reggie, in his capacity as medical consultant to Scotland Yard, into a remarkable case of suburban dysfunction. Arguably Bailey’s best tale, Toad is suspensefully and vividly told and there is much genuine detection (some having to do, appropriately enough, with food).

In “The Long Dinner,” a menu and the strange drawing on the back of it lead Reggie into the maze of a diabolical murder scheme. A serious moral question is explored here. Reggie is pretty intuitive here, but the plot is quite interesting. Reggie also reunites with his detective friend from France, who is a good character.

In “The Yellow Slugs,” one of the better-known Fortune tales (it was anthologized by Dorothy L. Sayers), Bailey delves interestingly into child psychology. Bailey often dealt with threats to children in his works and could sometimes be tiresomely sentimental, but “Slugs” is not overdone in this regard and in fact is rather realistic, modern and dark. Reggie also does some real detective spade work here, rather akin to what one might find in an R. Austin Freeman tale.

“Toad” and “Slugs” are particularly striking in that they are far removed from the aristocratic country house/quaint village settings so often associated with British Golden Age mystery. Instead, they focus on severe moral dysfunction in more modern-feeling suburban and urban settings.

The three other tales are worth reading as well, especially “The Angel’s Eye,” which was praised by Jacques Barzun. This one actually is set in an English country house and involves a locked room problem of sorts (though anyone expecting John Dickson Carr will be disappointed).

Published a year after Mr. Fortune Objects, A Clue for Mr. Fortune is another strong collection of six long stories: “The Torn Stocking,” “The Swimming Pool,” “The Hole in the Parchment,” “The Holy Well,” “The Wistful Goddess” and “The Dead Leaves.”

None perhaps has the depth of “The Broken Toad,” “The Long Dinner” or “The Yellow Slugs,” but several rank near the top of the Bailey works, being quite clever and entertaining.

Reggie Fortune is still bountifully bedecked with mannerisms some might fight irritating (he seems to have picked up the habit of quoting extensively in these later tales, though, thankfully he now looks less at people with the wondering eyes of a child), but he seems a mite less precious and more impressive in his role as an instrument of justice.

The best-known of the Clue tales probably is “The Dead Leaves,” which was anthologized in The Oxford Book of English Detective Stories, but it is not the actual best of the tales in Clue, in my opinion. My favorites are “The Torn Stocking,” “The Hole in the Parchment” and “The Holy Well.”

With “The Torn Stocking” we again see the exploration of a favorite theme of Bailey’s, that of the consequences of family dysfunction. The milieu is rather shabby urban middle-class. Reggie investigates the seeming suicide (head in the gas oven) of a teenage girl accused of shoplifting, with surprising results. His detective work is quite interesting.

“The Hole in the Parchment” sees Reggie and wife Joan vacationing in Florence, Italy (a number of the Fortune tales takes place in France, Germany and Italy). There the two become involved in a case involving theft and forgery, quite cleverly done.

In “The Holy Well,” Bailey gives bravura treatment to a classic detective story device. The story involves murder in rural Cornwall. Both the atmosphere and the plotting are first-rate.

Both Mr. Fortune Objects and Clue for Mr. Fortune are fine mystery short story collection that merit reprinting for a modern audience.