Thu 4 Mar 2010

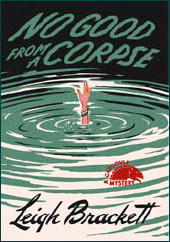

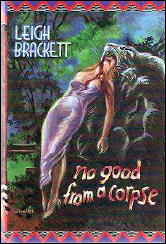

Reviewed by David L. Vineyard: LEIGH BRACKETT – No Good From a Corpse.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Reviews[4] Comments

LEIGH BRACKETT – No Good From a Corpse. Coward McCann, hardcover, 1944. Dennis McMillan, hc, 1998 [includes eight detective pulp stories plus title novel]. Reprint paperbacks: Handi-Book #32, 1944; Collier, 1964.

That’s the opening from Leigh Brackett’s tough private eye novel No Good From A Corpse. Edmond Clive is a private eye meeting the love of his life, Laurel Dane, a nightclub chanteuse at the Skyway Club, with what used to be called a past.

Laurel and Edmund have a past, too:

He kissed her.

“Hello, tramp.”

“Hello. Oh, Ed, I’m so glad to have you back!”

He looked down at her.

Cream-white skin, her face that had no beauty of feature and yet was beautiful because it was so alive and glowing, her red mouth, full and curved and a little sullen. He found it, as always, hard to breathe. He bent his head again.

They stood for a long time, the noise and the crowd flowing around them and leaving them untouched. Her lips were faintly bitter under his, with the taste of tears that had run down and caught in the corners of them.

Meanwhile Kenneth Farrar is hanging around Laurel:

Laurel Dane is on the spot and Clive is being warned off the case even as he reluctantly is drawn into a case involving an old enemy, Mick Hammond, and his wife Jane who wants to prevent “a divorce, or something more permanent.”

Jane brings with her brother and sister Richard and Vivien Alcott, and news that Mick is involved with Laurel Dane …

Clive turns Jane Hammond down, but when he meets Mick at the Skyway Club in Laurel’s dressing room he agrees to try and find the person writing threatening letters to him when someone takes a shot at Hammond and hits Clive instead.

Just a flesh wound, but Clive’s not the sort to take that lying down.

Especially when he takes Laurel Dane home and gets slugged unconscious only to wake up and find Laurel murdered:

The hard yellow glare showed Laurel. She lay on the floor, her cheek cradled on her forearm, her chin tucked under the curve of her bare white shoulder. She seemed relaxed and very comfortable. Clive knelt beside her.

There was blood at her nostrils. There was blood, not much of it, clotted in her hair above the nape of her neck. There was blood, just a little, on the knotted grip of Mick Hammond’s blackthorn stick, lying beyond her outflung hand.

He laid his fingers on her throat. The pulse was dead under them. The warmth was already going out of her flesh.

Laurel Dane was off her spot, for good.

Clive has to sell out Hammond to get Lt. Gaines of Homicide off his neck, but swears to clear Hammond — and avenge Laurel. His chief suspect is Dion Beauvais, a New Orleans tough Laurel was once married too, and Sugar March who works at the Skyway shows up to tell him someone Laurel was afraid of was at the club a few nights before.

Then Sugar ends up dead. An accident. Or was it?

Meanwhile Vivien Alcott is flirting heavily:

Clive laughed. “I hardly notice those things any more. You get hardened to it.”

She studied his face intently. “I guess a detective has to be tough. Are you tough, Mr. Clive?”

“How do I look?”

“Tough. Awfully tough.”

Clive is so tough it’s a surprise bullets don’t bounce off of him and blows to the head even faze him, but he’s drawn with an eye to the genre, and his toughness feels genuine. It helps that Brackett combines the almost poetic voice of her science fiction tales with a fine ear for dialogue. Anyone who has read her early science fiction tales knows those highly romantic stories often featured noirish heroes who wouldn’t have been out of place in Black Mask. Her specialty was space faring heroes who would have fit well with Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade.

It all turns on a psychotic and amoral beauty, and an ending that would have satisfied Mickey Spillane:

He did not answer. In the bleak light his face was without eagerness or cruelty or even hate.

“Your eyes are triangular, Ed. I never noticed that before. A killer’s eyes.” She laughed, raising her head on the strong column of her throat. “Even this won’t bring her back, Ed. She’s gone. Forever, gone.”

He let her go.

His belly and loins pressed her, no more strongly than with the force of a deep breath drawn in, but enough. Her heels slipped on the wet tile and went over the edge. She did not scream. Her body fell across the angle of the pool and her head struck the hard rim of the corner. He could hear her skull crack. There was no great splash when she went under.

Water came out over the deck almost to Clive’s shoes, and drained back again. One great bubble rose and burst, then smaller ones, a string of them, and then nothing. The ripples died.

In some ways No Good From a Corpse is almost a parody of a hard boiled novel, with Edmund Clive the toughest of the tough.

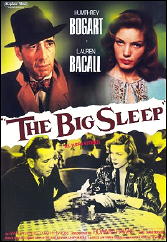

You can certainly see reading it how Howard Hawks came to choose Brackett to co-write the screenplay for The Big Sleep, though. Her bad girl is virtually a twin of Carmen Sternwood, and if Clive is more Sam Spade than Philip Marlowe the dialogue has the kind of bite we associate with Chandler and Marlowe. And the plot is nearly as convoluted as Chandler’s.

Brackett’s career needs no real introduction. She began writing moody noirish science fiction tales set on Mars and Venus (including co-scripting one with a young Ray Bradbury), ghosted books for Gypsy Rose Lee and George Sanders, married fellow science fiction author Edmond Hamilton, and wrote a handful of suspense novels, a western, and screenplays from The Big Sleep to Rio Bravo and The Long Goodbye, and something called The Empire Strikes Back.

No Good From a Corpse is her only hard-boiled private eye novel, but it’s a good one, full of snappy dialogue and Chandleresque observation. Like Chandler’s own first effort, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” the book is almost a parody of the form, but also like Chandler’s effort the real touch is there, and the writing has a feel for the true voice of the genre to it. It’s a shame Edmond Clive didn’t get to show his stuff in another case. He’s a memorable eye who deserved a longer run.

You can download No Good From a Corpse on-line from Munseys in the format of your choice.