Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

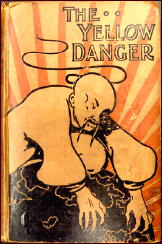

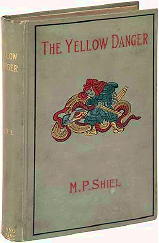

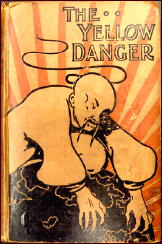

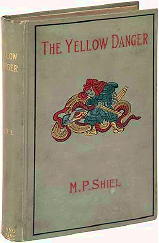

M. P. SHIEL – The Yellow Danger. Grant Richards, UK, hardcover, 1898. R. F. Fenno, US, hc, 1899. Reprinted many times.

Matthew Philips Shiel has to be one of the most eccentric writers of all time. Racist (despite the fact he was of mixed race himself), jingoist, and mystic, he is probably best known today for his Last Man on Earth novel The Purple Cloud and his stories about decadent sleuth, the neurasthenic Prince Zaleski, but for pulp fans he holds a special place — as the inventor of the “Yellow Peril” novel.

Before Shiel the “Italian Peril’ had been the biggest trend in popular fiction. Guy Boothby’s Dr. Nikola had a long successful career plaguing a series of English heroes (Nikola deserves to be rediscovered, and all the books are available to read free on-line as well as others by the popular and talented Australian Boothby), and Italian villains with ties to ‘the Black Hand’ and other such secret societies had shown up in the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Nick Carter, Sexton Blake, and books such as L. T. Meade’s and Robert Eustace’s The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings (also available free on-line and worth checking out, a clever and entertaining thriller from an earlier age).

The Yellow Danger is a novel in the sub-genre of stories known as invasion or future war novels that began with The Battle of Dorking and reached its highpoint with H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds. William LeQueux made a near cottage industry of these, and classics of the form include Erskine Childer’s prophetic Riddle of the Sands and Conan Doyle’s Danger! (which predicted submarine warfare in WW I).

Modern examples include Vandenburg by Oliver Lange, I, Martha Adams by Pauline Glen Winslow, SGB by Len Deighton, and films such as Red Dawn and Invasion USA.

I won’t go into the historical reasons for the rise of the “yellow peril” novel here. Suffice it to say that as much as anything the Boxer Rebellion, in which a fanatic secret society with backing from the Chinese government led to the siege of the embassies in Bejing (see Peter Fleming’s The Siege of Peking and the film 55 Days in Peking), and the subsequent military action by allied forces of the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and Japan among others, and the growing population of Chinese in Western cities and the sensationalist reporting of the era on the activities of the criminal “tongs” and the “yellow peril” only needed the right book to set the whole thing off.

The Yellow Danger was that book.

The novel opens as England faces a crisis in the East at the hands of the Germans, Russians, and French (Shiel was an equal opportunity jingoist), but it is at a simple garden party for a charity that we first meet the source of “the yellow danger” —

“Just allow me to introduce my friend here — Miss Seward — Dr. Yen How.”

In the light of the ’bus lamp Ada Seward saw a very small man dressed in European clothes, yet a man whom she at once took to be Chinese. With a wrinkled grin he put out his hand and shook hers.

He was a man of remarkable visage. When his hat was off, one saw that he was nearly bald and that his expanse of brow was majestic. There was something brooding, meditative in the meaning of his long eyes; there was a brown, and dark, and specially dirty shade of yellow tan to his skin.

He was not really a Chinaman, or rather he was that, and more. He was the son of a Japanese father by a Chinese woman. He combined these antagonistic races in one man. In Dr. Yen How was the East.

That “expansive majestic brow ” must surely remind readers of Sax Rohmer’s Dr. Fu Manchu and his “brow like Shakespeare.” And Shiel makes no bones about the doctor’s motives for his evil machinations —

Yen How was nothing if not heathen. He was that first of all.

His intellect was like dry ice. Though often secretly engaged in making The Guess, on the whole he despised all religions — faiths of the West, the superstitions of the East, he despised them all alike. He was full of light, but without a hint of warmth; and so lacked religious emotion.

It is not likely that ordinary ethical considerations would much influence the aims of such a man. He was like an avalanche, as cold and as resistless.

What was Dr. Yen How’s aim? Simply told, it was to possess one white woman, ultimately, and after all. He had also the subsidiary aim of doing an ill turn to all the other white women, and men, in the world.

To say the least the horse was out of the barn and bolting. You can’t accuse Shiel of beating around the bush. He jumps in with both feet. It’s not long before the evil Dr. Yen How has the world crumbling and the West trembling as the hordes of the East (ever since Genghis Khan Asian armies always seem to move in hordes).

Luckily for us England has men like Shiel’s Nietzschean hero John Hardy to call on —

There could be no doubt that John Hardy’s long-lashed, azure blue eyes possessed the faculty of

seeing.

As the crisis rises and the Asian hordes sweep across the west the consumptive but heroic Hardy rises in short time from unknown officer to Admiral of the fleet.

Under the English banner the treacherous Russians, Germans, French and others rally, and Kaiser Bill himself leads an army under the Union Jack in a great land battle, but it is Hardy who must destroy Dr. Yen How and his hordes, and his choice of weapon is perhaps the most far seeing and startling of Shiel’s predictions.

Hardy uses the young woman, Ada Seward, who Dr. Yen How desires, to get to the leader of the Asian invaders and infects the Dr. and the invading armies with plague — a bit of payback since the invading Mongols introduced the disease to Europe in the first place back in the days of Genghis Khan.

To be fair, mass murder weighs heavily on Hardy in a chapter entitled “Hardy’s ‘Crime'” —

He was no longer sane. His hand was thicker that itself with his brother’s blood. His final hour of darkness was hastening to meet his life. All his sky was an ink of clouds. Now again, he tarried, cowering, in Gethsemane.

The Asian armies die by the millions, Dr. Yen How succumbs to his ‘unnatural desire’ for a white woman, and the triumphant Hardy, the beloved leader of the white race, dies of the consumption eating away at him, leaving the world in the safe hands of the Pax Britannica, all of Europe now under the firm hand of the Union Jack from the English Channel to the Russian Steppes.

The Yellow Danger is relatively hard to find but you can download a facsimile in pdf format or read it on-line.

It’s a remarkable book, not just for its distasteful jingoism and racism, but also because so many of the cliches and stereotypes of the sub genre are already present: the stalwart English hero; the inhumanly cold intelligence and yet base passions of the Asian villain; the fear of racial impurity; the swarming hordes of sub-human and alien forces; and the fear of the unknown.

Nor is The Yellow Danger Shiel’s only contribution to the invasion novel and the paranoid fear of the foreign. Lord of the Sea is the story of an English Jew who conquers the seven seas and is ultimately destroyed by his desire for a pure English woman. Luckily the “Jewish Peril” didn’t quite catch on despite the nonsensical and wholly fictitious Protocols of Zion and rampant Anti-Semitism.

No doubt about it, this can be unpleasant stuff, but it also has historical import both socially and to the genre as a whole.

It was Shiel who moved the world’s eyes East and spawned a long line of “Yellow Perils,” a genre that still lingers long past the heyday of the Fu Manchu’s, Dr. Wu Fang’s, the Shadow’s Shiwan Khan, and Dr. No’s of yesteryear. The list of Asian super villains is impressive and still growing.

The genre is far from dead even today (although the “yellow peril” currently has been replaced by the “Islamic peril”). Clive Cussler has written at least two novels that fall in this category (Dragon and Flood Tide) and is hardly alone. One hundred and twelve years later popular fiction is still haunted by the “yellow peril” stereotype.

A new Fu Manchu novel appeared in 2009 (The Terror of Fu Manchu from Black Coat Press). There’s even a distaff “yellow peril” with Sax Rohmer’s Sumuru and Andre Caroff’s Madame Atomos (also being reprinted by Black Coat Press), and books like Alexander Cordell’s The Deadly Eurasian and Richard Condon’s The Whisper of the Axe send up of the whole thing offering a new take on old cliches.

Richard Jacoma’s The Yellow Peril is a good example of having it both ways, a “yellow peril” novel seen through modern eyes, and K. K. Beck’s The Revenge of Kali Ra (reviewed here ) sends the whole thing up as well as taking shots at Hollywood and Sax Rohmer.

But be warned: If you are easily offended or bothered much by what is or is not politically correct, The Yellow Danger may be hard going.

Shiel was a very unpleasant man by all accounts and eccentric as both a writer and a human being. Still, if you are interested in the history of the genre and the origin of many of its stereotypes and cliches this one is hard to ignore.

In its wake march armies of shadowy geniuses hidden in the foggy street of Limehouse or Chinatown and gathering their forces in distant exotic lands.

We may have outgrown some of Shiel’s more obvious prejudices, but it may be a wise thing to compare them to our own modern flaws and ask ourselves if we have really moved that all that far in the one hundred and twelve years since The Yellow Danger first saw print.

There are writers today — Brad Thor and John Ringo come to mind — often found on the bestseller list, whose popular books are, in their own way, no less sensationalist, jingoistic, and intolerant as Shiel’s work.

We are in no position to condemn without first examining our own failings.

Note: The anthologies It’s Raining Corpses in Chinatown and It’s Raining More Corpses in Chinatown edited by Don Hutchinson (Starmont House) offer a good selection of “Yellow Peril” stories from the pulps plus a good history of the genre and bibliography of “Yellow Peril” fiction from writers like Frank Gruber, Steve Fisher, Richard Sale and others for those interested.

COMMENT [02-17-10] From Jess Nevins, author of Fantastic Victoriana —

To be precise and in terms of the facts, Shiel didn’t invent the Yellow Peril novel. I believe that David has grossly overstated Shiel’s development of the trope. It was already commonly used by the time Shiel wrote his book.

I wrote about this, at length, in Fantastic Victoriana, but, briefly:

Numerically, the Italian Yellow Peril peaked with suspense fiction, in the 1870s. Anti-Asian sentiment rose from mid-century, and in both Britain and the US the 1880s were when it surged upwards, and not just in the U.S. It was Albert Robida, in France, who wrote “La Vorace Albion” (1884), with its various Asian villains.

But in the US you’ve got Robert Woltor’s A Short and Truthful History of the Taking of Oregon and California by the Chinese in the Year A.D. 1899 (1882), you’ve got Emma Dawson’s “The Dramatic in My Destiny” (1880), Ellen Sargent’s “Wee Wi Peng” (1882), the various dime novel Yellow Peril villains (far outnumbering Italian villains), culminating in Kiang Ho (1892), enemy of Tom Edison, Jr.

You’ve got Robert Chambers’ Yue Laou, in The Maker of Moons (1896), and you’ve got C.W. Doyle’s Quong Lung (short stories, 1897-1898).

It was an established literary trope and even a cliche by the time Shiel got to it. It predated the Boxer Rebellion in non-fiction and fiction by, oh, about 40 years. Shiel *capitalized* on it, but he didn’t establish it. Yellow Papers were in the British story papers and American dime novels a full decade before Shiel.

RESPONSE [02-17-10] David’s reply:

I am not suggesting Shiel invented the idea of Asian villains in popular fiction. Certainly the influx of Asians on the Western Coast of the United States after the Civil War and the growth of Chinese sections of major cities in the West were major contributing factors in the growth of the field.

This was complicated by the language and cultural barriers and the tendency of the Chinese and Japanese to stay in their own communities (not that they had much opportunity to move out of them if they had wanted to). Just as the Irish, Italians, and Jews all suffered similar demonization at various times as their communities grew in major cities.

But The Yellow Danger is generally attributed by most critics (Don Hutchinson, Robert Sampson, Brian Aldiss, and others) as the book which put the “yellow peril” on the map of popular imagination. Historically Shiel’s book helped to move a vague prejudice from the background of popular culture to one of the most recognized stereotypes of 20th Century popular imagination.

In any case no one can argue that Sax Rohmer and Fu Manchu “invented” the genre and yet no one can argue that the “yellow peril” would still be with us without the good doctor’s influence.

First is not always important in popular fiction. Sherlock Holmes wasn’t the first detective, James Bond wasn’t the first post war secret agent, Fu Manchu wasn’t the first Asian super villain, the Virginian wasn’t the first western, Tarzan not the first feral man, John Carter not the first interplanetary traveler, and Zorro wasn’t the first masked caped hero with a secret identity — none the less their role is important and vital to the sub genres they represent. The Yellow Danger was neither new nor unique, but it was important in establishing a still existing sub-genre.

LATER:

I do regret loosely using “inventor” as if there had been no Asian villains before Shiel, but I do think Jess vastly underrates the importance of the Boxer Rebellion in the rise of the genre in the 20th century, and the importance of Shiel’s book — which is hardly unique to me, as I pointed out earlier.

When I was researching Chinese secret societies and particularly the Boxers for Dr. John Y. Moon (former Foreign Minister of South Korea and head of the History Department of the University of Mexico in Mexico City), he brought the Shiel book to my attention as the “turning point” in the use of the “yellow peril” in fiction (ironically Dr. Moon was a Rohmer and Fu Manchu fan and introduced me to “yellow peril” fiction — though as he laughingly pointed out, Fu Manchu was Chinese, not Korean — and though he never missed a Wo Fat episode of Hawaii Five-O either). I grant his opinions and work influenced my article (and a life time interest in secret societies in general in fact and fiction).