Wed 16 Sep 2009

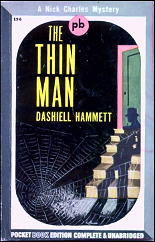

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Thin Man. Alfred A. Knopf, 1934. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including Pocket #196, 1942.

I read Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man back in High School, and I didn’t like it much because it wasn’t The Maltese Falcon. But just lately, some forty years later, I figured I’d give it another try.

I sort of wish I didn’t remember the movie (MGM, 1934) so well, or maybe that the film hadn’t been so faithful to the book. It would have been nice to come back to this fresh, not knowing the ending, just to see how well Hammett constructed this tricky mystery, a tale so well put together that one scarcely knows where to look among a cast of cleverly conceived (and, for the most part, sympathetically observed) suspects — or just what it is we’re looking for.

Is The Thin Man about the murder of Julia West or is it about the con game she was working on the missing Wynant? Is it concerned more with a missing-persons case, or with the kinky, incestuous Wynant family? Whatever the puzzle, it reads quite nicely, with a sense of humor that sneaks up on one very pleasantly indeed.

I might carp that Nick Charles, the narrator/detective, tells the story rather flatly, which contrasts a bit too sharply with the wise-cracks he and Nora keep throwing around in the dialogue. Compare this to the colorful narration Raymond Chandler gave to Philip Marlowe and you’ll see what I mean: Marlowe is a consistent smart-ass, but Nick Charles only gets colorful when he’s talking to the other characters.

But that, as I say, is just carping. The Thin Man has a reputation as a mystery classic, and I was happy to discover how richly it deserves it.

By the way, the movie version, first in a long line of “Thin Man” films, is quite faithful to the book, and generally well thought-of, but it doesn’t hold up quite as well, due largely to a clunky and obvious-red-herring opening sequence (not in the novel) that looks to have been tacked on rather hastily, and someone’s insistence on giving everyone in the cast a Guilty Close-Up.

You know the kind of thing I mean: someone makes a remark or picks up a clue and we cut to a shot of Maureen O’Sullivan or Cesar Romero looking like their pants fell down. It’s the sort of thing they were doing in the Charlie Chan films over at Fox, and it seems embarrassingly out of place in a film that’s mostly fast-moving and sophisticated.