A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

EUGÈNE SUE – The Mysteries of Paris. W. Dugdale, UK, hardcover, 1844. Harper & Brothers, US, 1843. Translation of Les Mystères de Paris: Paris, 1843-4. Silent film: Esclair, 1909 (scw & dir: Victorin Jasset). Also: SCAGL, 1913. Also: Cinematographes Phocea, 1922, as Les Mystères de Paris (scw: Charles Burguet, Andre Paul Antoine; dir: Burguet). Also: Bennett, 1922, as The Secrets of Paris (scw: Dorothy Farnum; dir; Kenneth Webb). Sound film: Franco-American, 1937, as Les Mystères de Paris (The Mysteries of Paris) (scw & dir: Felix Ganders). Also: Unidex, 1962, as Les Mystères de Paris (The Mysteries of Paris) (scw: Jean Halain, Pierre Foucault, Diego Fabbri; dir: Andre Hunebelle).

This feulliton, or French newspaper serial, was one of the most influential novels of the 19th Century. While it is little known today, when it first ran as a weekly serial it outsold Alexandre Dumas pere’s The Count of Monte Cristo, and was praised by no less a critic than Victor Hugo, who called its author, Eugène Sue, the “Dickens of Paris.”

Despite its title, Mysteries of Paris is neither a mystery nor a detective story in any formal sense, it is however an early example of the crime novel and thriller and helped to establish many of the tropes of popular fiction that still linger today. Heroes from Zorro to the Shadow to Batman owe a debt to Sue’s Prince Rodolphe (in some editions Rudolph), the mysterious man in black haunting the back alleys of crime and poverty ridden Paris.

Eugène Sue was a minor nobleman with a political bent. He was an avid socialist and critic of the Catholic Church — particularly the Jesuits who feature as the villains of his classic The Wandering Jew. He spent much of his career in semi-exile for his criticisms of Louis Napoleon, like his friend and fellow author Hugo.

Sue also has an ironic role in history: In one volume of his massive Mysteries of the People, Sue created a fictional document detailing how a Jesuit conspiracy operated and secretly ran the world — when this ‘document’ was plagiarized by a Russian propagandist and the references to the Jesuits changed to Jews the document became the inflammatory and wholly fictional Protocols of Zion; an irony that would have horrified the liberal Sue.

But Sue’s role in popular literature is secure with his two best known works, The Wandering Jew and Mysteries of Paris, the latter followed by countless imitations, with Mysteries of London, Prague, Berlin, and even New York to follow. Its influence extended well into the early 20th Century (fans of the TV series Friends might recall the “Mysteries of New York” poster on the wall in Joey and Chandler’s apartment).

Prince Rodolphe of Gerolstein appears in Paris as a mysterious man in black. He is on the trail of Fleur de Mal, a child orphaned by an act of carelessness in his youth.

As he searches the lowest and vilest of Paris slums he becomes an early model for the justice figure or avenger, seeking both redemption for himself and justice and mercy for the downtrodden but good people he finds driven to crime and degradation by poverty and social injustice, befriending and reforming many of the criminals and semi-criminals he encounters and even forming a sort of ‘thieves court’ with himself as judge which deals out fair but swift justice among a people who have no trust of the corrupt real courts and laws written and administered to oppress them.

Sue threw himself into the novel with real zeal, and his use of Parisian street argot is a remarkable accomplishment. Any historian wishing to know what life was like in the streets of mid-19th Century Paris would be advised to carefully read Sue’s novel. Like Dickens to whom he was often compared, he had a real affection for the people of the streets of Paris though a realistic eye for detail. In some ways Sue’s modern disciples are writers like W.R. Burnett, Elmore Leonard, Joseph Wambaugh, and George V. Higgins.

There is, as might be expected, a good deal of melodrama, pathos, bathos, and hokum in the novel. Its serial origins show, and at some 1300 pages in unabridged editions, it is far from a casual read. It gives the term Victorian triple-decker new meaning.

But it is also filled with exciting scenes, interesting characters, and if Sue lacks Dickens’ more literary qualities, he quite shares his ability to tell a story and to involve the reader in the lives of his creations. Mysteries of Paris is what a friend of mine used to call a “thumping good read.”

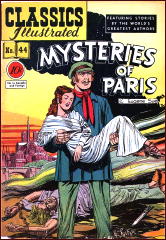

Mysteries of Paris has been filmed and adapted to other media countless times since the silent era in many languages. There are television mini-series and even animated versions, and it was one of the early books adapted by Gilberton’s Classics Illustrated Comics.

Perhaps the best film is a 1962 Arthur Hunebele production with Jean Marais (Orphee, La Belle et la Bete) as Roldolphe, Dany Robin as Irene, and Jill Haworth as Fleur de Mal. By necessity it is a very abridged version of the story, but told in a lively manner by a director best remembered for his campy Fantomas films with Marais in a double role as the super criminal and his nemesis Juve.

Mysteries is still widely read in Europe and considered a pop classic. It is less well-known here, in part because there has never been a really good translation of the novel nor an annotated edition, both of which are long overdue.

But Mysteries is an important book in the development of the mystery genre, taking inspiration from Poe, Dickens, Collins and others, and in turn inspiring many of the works to come.

Currently there are several editions available and some older reprints are relatively inexpensive to collect. I would suggest you avoid the abridged editions and go for the massive entire book. You might also want to read The Wandering Jew which was recently chosen by Thomas Disch for the 100 Best Horror Novels of all time.

Sue really is neglected in this country and unjustly so. This is a novel that deserves to be rediscovered.

NOTE: The bibliographic information given at the top of this review was taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, as just now corrected. (The publisher of the first UK edition has been changed to the one you see above.)

[UPDATE] 08-21-09. Based on David’s statement: “Mysteries of Paris has been filmed and adapted to other media countless times since the silent era in many languages…,” and using IMDB as a guide, Al Hubin and I have come up with the following films, etc., which should be added to those listed in the credits above. These will appear in the next installment to the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV:

● Silent film: Pathe Freres, 1911, as Les Mystères de Paris (dir: Albert Capellani)

● Silent film: Hub Cinemagraph, 1920, as The Mysteries of Paris (scw: Stanley J. Worris; dir: Ed Cornell)

● Silent film: Phocea Film, 1922, as Les Mystères de Paris (scw: Andre-Paul Antoine, Charles Burquet; dir: Burquet)

● Film: DisCina, 1943, as Les Mystères de Paris (scw: Maurice Bessy; dir: Jacques de Baroncelli)

● TV movie: France, 1961, as Les Mystères de Paris (scw: Claude Santelli; dir: Marcel Cravenne)

● TV movie (miniseries): Caravelle International, as Les Mystères de Paris (scw: Mario Benedicto; dir: Andre Michel)