Tue 18 Aug 2009

A Review by David L. Vineyard: JOHN WELCOME – Stop at Nothing.

Posted by Steve under ReviewsNo Comments

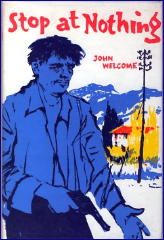

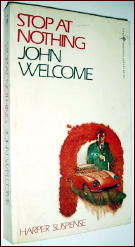

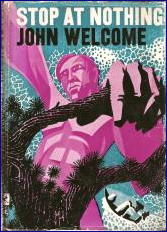

JOHN WELCOME – Stop at Nothing. Faber & Faber, UK, hardcover, 1959. Alfred A. Knopf, US, hc, 1960. Paperback reprint: Perennial Library P665, US, 1983.

John Welcome was a British solicitor, anthologist, and novelist whose greatest claim to fame was that his list of clients included his long time friend Dick Francis. As an anthologist he edited a series of books such as Best Racing Stories and Best Secret Service Stories, that managed to reprint some less common stories than the usual retreads.

As a solicitor he is in a long tradition of mystery writers including John Buchan, Dornford Yates, and Michael Gilbert, and his novels all have some of the qualities of those writers.

Stop at Nothing is the second of his novels, and does not feature his series hero Richard Graham, a former steeplechase jockey. In this one the hero is Simon Herald, an amateur race driver (Formula One) who is a modern variation on the sportsman heroes of another age.

That said, Herald occupies a world much closer to ours than that of Richard Hannay. As the back cover of the Perennial paperback edition says:

“Pink champagne and barbiturates, Benzedrine for breakfast, and a glass of wine at Cap Ferat evoke the giddy glamour and insidious shadow of danger for Simon Herald …”

It’s the world of the Jet Set and Euro Trash, new money, jaded appetites, and casual drug use, and at forty, Simon Herald doesn’t really fit into it. Still he accepts an invitation to a party at Clevendon Court (one of the two genuine Robert Adam houses in Ireland) held by the wealthy Mantovelli.

There he meets Roddy Marston, a young riding champion in a bad temper, Stuart Jason, a tough polished thug who works for his host (“he fell in love with violence during the war and can’t forget it”), and Mantovelli himself: “His face was seamed and wrinkled and scarred with lines of age, he had very bright blue eyes as hard as polished steel.”

An invitation to visit Mantovelli on his upcoming trip to France involves him with Roddy Marston’s sister, Sue, and finds him reluctantly helping the obnoxious Roddy as a result.

This is familiar thriller territory, and you shouldn’t expect any surprises along the way. This is the literary equivalent of a good blended Scotch, smooth but with an appreciable kick. Magnificent mountains in Provence, the beauty of the Riviera, and powerful Bentley’s, Rolls, Ferrari’s, and Aston Martin’s are the accouterments of people playing dangerous games with lives often above or beyond the reach of the law.

Simon Herald’s skill behind the wheel and his cool nerve make him the ideal man to negotiate these obstacles, and ultimately put pay to the nasty Mantovelli and his death-haunted henchman Jason.

The writing is accomplished and the plotting sure. Barzun and Taylor suitably praised it, though they did ask rather archly if you could actually see lights, much less breathe, from the presumably air-tight boot of an Aston Martin.

Still, minor things like that can be ignored when the thuggery is this sophisticated, the atmosphere this posh, and the derring-do starts on page one and doesn’t end until the last word on the last page.

Anthony Boucher called it “… lively, vivid, and highly readable…,” which is exactly what you can expect.

Welcome wrote several more novels, mostly international intrigue in this tradition with Richard Graham as the hero, as well as a good historical novel, Bellary Bay.

Almost all of them have the qualities of a good film, say Hitchcock in To Catch a Thief mode, nothing serious, but a kind of light and accomplished professional thriller that too few writers today seem capable of writing.

This is the perfect antidote to today’s bloated thrillers full of lunk-headed supermen and villains who wouldn’t pass muster in a bad comic book.

Stop at Nothing is the next best thing to visiting the Cote d’Azur and meeting a beautiful girl for a bit of romance and adventure and glamour and good life on your own, and a good deal less tiring and dangerous. It is what used to be meant by the term escapist.

At least, Welcome doesn’t have the hero drive from Gibraltar to Cannes in two hours like a certain geographically challenged best-selling thriller writer I recently encountered.

Oh for the days when thriller writers could actually read a map.

And write.

![ANONYMOUS [WYLIE] The Smiling Corpse](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg809/Anon-Corpse.jpg)