Tue 14 Jul 2009

Reviewed by Marvin Lachman: P. D. JAMES – A Mind to Murder.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

by Marvin Lachman

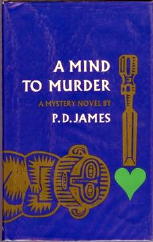

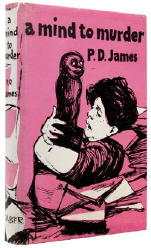

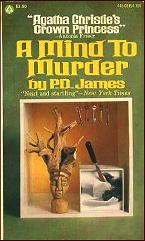

P. D. JAMES – A Mind to Murder. Faber & Faber, UK, hardcover, 1963. Charles Scribner’s Sons, US, hardcover, 1967. Reprinted many times, both hardcover and soft, including Popular Library, paperback, US, 1976. (All shown.)

Although mystery fiction has had more than its share of characters with psychiatric conditions, there have been few books set in psychiatric institutions.

Coincidentally, two of these are currently available in paperback, and they are both worth seeking out. A Mind to Murder is P. D. James’s second novel and draws heavily on her own experience for its setting, a London psychiatric outpatient clinic.

The victim is a hospital administrator, a position Miss James held in the British Civil Service System.

Not only does the author know the workings of such a clinic, but she also knows the heartbreak of mental illness firsthand, since her husband, a physician, was hospitalized due to that condition for most of the twenty years before his death in 1964.

Authenticity is the strong point of this book, along with the writing,which is civilized and perceptive; its plotting adequate, but it is not as good in that regard as the 1962 James debut novel, Cover Her Face.

James is very adept at characterization, especially as regards Adam Dalgliesh, her series ,detective, who shows depths not often found in sleuths who solve the kind of classic puzzles James presents. Her skillful writing evokes considerable poignancy in describing his personal life.

There is also a superbly written section about his searching the apartment of the victim, and Dalgliesh has enough empathy to realize that the necessary act is a violation of a dead person.

If P. D. James seems to have received an inordinate amount of praise in recent years, do not begrudge it to her. She, more than most, combines the ability to plot interesting puzzles with the writing skill to observe society create real characters, and write with intelligence and sophistication.

Editorial Comment: The review by Marv of the second of the two paperback mysteries he refers to will appear on this blog soon.