Thu 19 Aug 2021

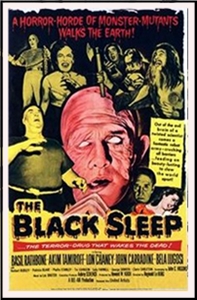

A Horror Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: THE BLACK SLEEP (1956).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[4] Comments

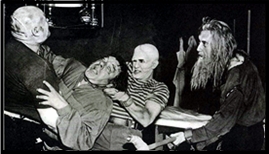

THE BLACK SLEEP. Bel-Air Productions/United Artists, 1956. Basil Rathbone, Akim Tamiroff, Lon Chaney, John Carradine, Bela Lugosi, Herbert Rudley, Patricia Blake, Phyllis Stanley, Tor Johnson. Director: Reginald Le Borg.

The eponymous black sleep in the movie’s title is not a state of being. Rather, it is a thing – a fictional mysterious potion from the Indian subcontinent that puts its users into a deep, quasi-hypnotic state. It’s therefore fittingly ironic that a movie about a sleep-inducing substance is, for the first thirty minutes or so, rather soporific itself.

Despite the best efforts of the always enjoyable Basil Rathbone to liven things up with philosophical speeches about medicine and the human condition, the first half of The Black Sleep is a stilted, talky affair.

All that changes in the second half. That’s when this Bel-Air production decides to let its inhibitions fall asunder and for schlocky insanity to ensue. How insane, you ask? Let’s just say that John Carradine portrays a stark raving madman locked in a basement dungeon who believes he is a Crusader out to conquer Jerusalem.

Like many other horror films from the late 1950s and early 1960s, The Black Sleep is set in Victorian England. Rathbone portrays Sir Joel Cadman, an esteemed surgeon who embarks on a series of highly unethical medical experiments on live human subjects. He has his reasons, of course. His beloved wife has been in a coma for months and he believes that, with the right among of experimentation on others, he can find a way to successfully operate on her and bring her back to full life.

Cadman, in a conniving manner, enlists the aid of Dr. Gordon Ramsay (Herbert Rudley) to further his work. It’s only a matter of time, however, before Ramsay learns the true nature of Cadman’s vicious work.

The true star of this horror film, however, is neither Rathbone nor Rudley. That honor goes to veteran character actor Akim Tamiroff. Here, he portrays Odo, a Romani tattoo artist in cahoots with Sir Joel (Rathbone). With a smile a mile wide and his notable South Caucasian accent, Tamiroff chews the scenery and makes the whole affair far livelier than it would have been in his absence.

Final word about the billing: aside from John Carradine, the movie also has two other horror greats listed in the cast; namely, Lon Chaney Jr. and Bela Lugosi. Neither actor has any lines. Chaney portrays a brute whose brain and mind were destroyed by Cadman’s experiments, while Lugosi portrays Cadman’s mute butler.

It’s always nice to see these greats on screen, but there’s something obviously very sad about how low both actors’ star powers had fallen by the mid-1950s. This was to be Lugosi’s last complete cinematic role, excepting the truly atrocious Plan 9 From Outer Space (1957).