REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

STEVE FRAZEE – Desert Guns. Dell 1st Edition A135, paperback original, April 1957. Thorndike Press, hardcover, 1998.

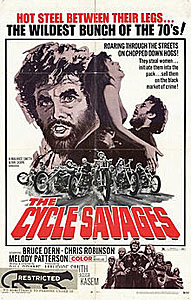

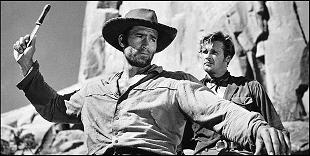

GOLD OF THE SEVEN SAINTS. Warner Brothers, 1961. Clint Walker, Roger Moore, LetÃcia Román, Robert Middleton, Chill Wills, Gene Evans. Screenplay by Leigh Brackett and Leonard Freeman, based on the novel Desert Guns by Steve Frazee. Director: Gordon Douglas.

Wind-sculptured into curving smoothness, the ridges of sand rose seven hundred feet toward the sky, Rainbolt saw the wind racing on the delicate spines, laying the sand before it like the manes of running horses.

No tree or rock or permanency of any kind broke the flowing architecture. There was only sand that for a million years had been gathered here by wind currents sweeping across the great San Luis Valley.

Steve Frazee is, perhaps, the most underappreciated Western writer to come out of the late pulp era and practice his considerable skills in hardcover and paperback. He had an early success with his novel Many Rivers to Cross, a rollicking story of the taming of a mountain man that became a MGM film with Robert Taylor and Eleanor Parker, and Hollywood would call on him more than once, but he never seemed to achieve the place he should have among writers like Louis L’Amour, Will Henry, Elmer Kelton, and the like.

This despite the fact he also wrote non-Westerns like Sky Block (something of a minor collector’s item), Running Target, and High Cage (these last two both films, the latter as High Hell, with John Derek). He also wrote Whitman big books featuring the likes of Cheyenne, Maverick, and Zorro, often illustrated by renown comic book artist Alex Toth, and thus doubly collectable.

Desert Guns opens in 1853 with its heroes, young Jim Rainbolt and his mentor and friend Shaun Weymouth, already on the run along the Sangre de Cristos in New Mexico from the hideously disfigured but canny Green River and his constant companion, the sadistic brute Frank McCracken, both of whom are after the Spanish gold the two have found, and plunging us directly into the action at hand.

Frazee is particularly adept here at capturing the otherworldly feel of the high desert and the haunted atmosphere of the Sangre de Cristos. I’ve spent a good deal of time there over the years, briefly living in Los Alamos, and I can attest to the “weird, whining sort of sound, low and mighty,†that you can hear in a hollow and the sand on “the steep sides of the hollow (that) was running like fine brown snow†the sand playing it’s “unearthly music.â€

In short order Rainbolt and Shaun encounter the Hudsons, father and daughter Gail building a life on a small ranchero, Hudson an arrogant Virginian with little hospitality and less time for a couple of ‘field hands.’â€

With scant help from the arrogant Hudson, the two decide to bury the gold and seek help from Diamasio Gondora the “one man on the Hueferano you can trust.†It’s there they meet the boy Chico, and Gondora’s half Indian daughter Paisano. By now you should be able to smell the triangle that develops between the blonde civilized Gail, the wild half Indian Paisano, and Rainbolt, a further complication to everything.

The basics of the plot are simple: gold makes men mad and greedy and there are more important things. Along the way there is graphic violence, torture, mayhem,treachery, and redemption. Rainbolt grows from youngster to man and Shaun achieves a sort of mythic status as the ideal man of the West, the last of a breed, more worried that the gold will change his wanderer’s life than about losing it.

The shifting treacherous sands play a central role both in the plot and thematically. They represent not only shifting loyalties and fortunes, but also inconstant nature, that takes no sides, but sometimes favors one and not the other, and sometimes favors no one.

Desert Guns is no Treasure of the Sierra Madre, but it is an entertaining Western, superbly written, and with more to offer than the simple story it tells. It is Frazee at his best, which is very good indeed, involving you in the fortunes and fate of Rainbolt and Shaun at a much deeper level than most Westerns.

The film, Gold of the Seven Saints, changes many of the elements of the book, Clint Walker is Rainbolt, but the older and more seasoned of the two, while Roger Moore as Shawn Garrett is an Irishman. Still, it has a fine script co-written by Leigh Brackett, solid direction by Gordon Douglas, and though it is unaccountably a black and white film, location settings capture much of the feel of the book, and fine character actors people it playing to the broader elements with some zest, despite the fact it often seems like an extended episode of a Warner Brothers fifties television Western with so many familiar faces from the small screen.

I happen to like it much more than many others do, but whatever its virtues it doesn’t rise to the standard of the Frazee novel it is based on. But don’t let that stop you from seeking out Desert Guns. I found a hardcover copy on Amazon for $4, so it isn’t impossible to find.