REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

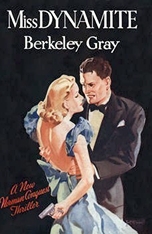

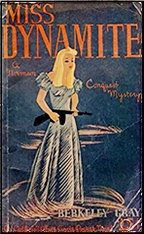

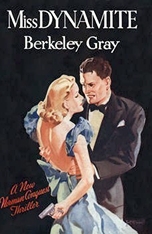

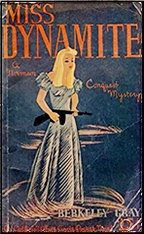

BERKELEY GRAY – Miss Dynamite. Norman Conquest #3. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1939. Collins White Circle Pocket Novel #85. paperback, 1945. No US edition.

“Norman Conquest Again!â€, proclaims the blurb inside the title page and then proceeds to give away the entire plot about as blatantly as you can:

When Norman Conquest shared a poachers meal in a quiet Suffolk field, even his razor-edged sixth sense couldn’t have warned him about the sinister events ensue from that casual meeting. From the murder of the unpleasantly efficient Sgt. Roper to the thrilling boodle-collecting finish, the Gay Desperado finds an opponent worthy of his steel in the lovely but unscrupulous Primrose Trevor. To him she’s just a helpless girl in the power of a crooked father badly in need of a knight errant. But fortunately Joy Everard is there to checkmate this other feminine influence and finally saves her Man from extinction at the hands of her rival.

Talk about giving the game away.

To be fair, no one picking this book up could imagine Norman Conquest wouldn’t get the best of any villain and collect the boodle.

Berkeley Gray’s first entry in the Conquest series just missed winning a thousand pound prize for best new thriller. John Creasey won the contest with Meet The Baron.

Still, Gray got a contract.

Miss Dynamite was the third entry in Berkeley Gray (E.S. Brooks) long running (1938-1968) series about Norman Conquest, 1066, the Gay Desperado (Mister Mortimer Gets the Jitters and Vultures Ltd., also 1938, proceeded this one) who made his debut in the pages of the Thriller magazine that had given birth to Leslie Charteris the Saint, John Creasey’s the Toff, Barry Perowne’s Raffles revival, and many more of the gentlemen adventurers gracing British popular fiction of the era.

Six foot of gray-eyed nitro, Conquest was the Saint or the Toff in high drive, his adventures driven by his creator, who was one of Fleetway’s chief staff writers in penning the adventures of Sexton Blake, Nelson Lee, and Gray’s own popular creation Waldo the Wonderman (very much a forerunner of Conquest). Hitting the ground running is hardly adequate to describe Conquest.

For sheer enthusiasm, high spirits (no one enjoyed cornering a bad guy and explaining how he had outsmarted them more than Conquest), gadgets (his cigarette lighter was a likely to blow down a wall as light a cigarette), and gusto, even the Saint might seem melancholy. Norman Conquest loved being a desperado. He practically reaches off the page and grabs the reader by the lapels he’s so eager to drag us into the action.

The Saint and the Toff were primarily urban crime fighters with forays to criminal hideouts in the country, but Norman is often found traveling to a rural or village setting where he uncovers danger. He gets abroad more often in that era than most of his competitors.

Unlike most gentleman adventurers Conquest had a steady girl from the start, Joy Everard, aka Pixie, eventually Mrs. Norman Conquest (another variation from the other nom de guerre boys). True, the Saint had Patrica Holm, but she wasn’t around that long, and Simon, while faithful, eventually just forgot about her. Joy was there from the start and stayed there for the entire run of the series.

And Joy, unlike say Phyllis Drummond or Felicity Dawlish, wasn’t just there to be kidnapped. More likely Joy would show up and pull Conquest’s ashes from the flames before he was terminally singed, because when it came to women Norman Conquest was more a mooning schoolboy than Gay Desperado.

He never met a blonde he didn’t like.

Primrose Trevor is certainly near the top of that group (Says Joy: “Primrose my foot! Her name’s Poison Ivy!â€).

It is hard to imagine Simon Templar, Richard Rollinson, or John Mannering (the Baron) being led down the garden path as often or as near fatally as Conquest. Granted Richard Verrill, Blackshirt, had the mysterious voice of the woman on the phone blackmailing him enticingly to turn his criminal activities to crime fighting, but he recognized a bad girl when he saw her. For Norman Conquest every blonde was a goddess even if she turned out to be a she devil like Primrose Trevor.

A girl was standing on the stile, the flickering firelight illuminating her trim figure, her sweet face, and her mass of wavy blonde hair.

That’s all it takes and even Norman is wondering why he is spinning tales to her about writing thrillers and doing research when what he is there to do is relieve her crooked father, Sir Hastings of his ill gotten gains with his gang of international jewel thieves in the fine tradition of not quite outlaw gentlemen adventurers everywhere. But when she “presses her quivering body against Norman and gave him the works,†our boy was lost.

Conquest practically cornered the market on femme fatales in this sub-genre, and fell for every one of them.

Not that Norman still isn’t the most ruthless of the desperadoes of the era. He is closer to James Bond in that and his penchant for gadgets. Conquest even faces death by pore suffocation by being painted gold in one adventure.

Edwy Searles Brooks was fifty years old in 1938 when Fleetway Publications decided they needed new blood. After some six million estimated words over a career that lasted back to 1918, some 20,000 words a week for twenty years, Brooks was out of gainful employment, sidelined as too old for his schoolboy audience.

There was a flame that burned in Brooks chest though, and with hardly a moment to breathe he turned to a new pseudonym, and a new character, Berkeley Gray and Norman Conquest, and had an instant hit. Then just to prove he could do it again he began writing as Victor Gunn about Inspector Bill “Ironsides†Cromwell and again struck black gold, the ink and not the petroleum kind.

Popular over most of the English speaking world (they never really cracked the American market, but then Creasey didn’t until the Sixties successfully), the books were reprinted in multiple languages, there was a Norman Conquest movie (with Tom Conway) and in Germany an Ironsides krimi film.

Neither series reads as if it was written by a washed up tired fifty year old man who had burned out after writing six million words for boys.

As always, the long suffering Pixie stands by her man though the “Hullo Pixie Hullo Desperado†business is a bit more curtailed than usual in this one. Even when Conquest is fooling around with blondes, Joy remains his partner, but she doesn’t have to like it with or without the wedding ring..

How shocked would poor Conquest be to hear his lovely Primrose talking to her father when he fears Conquest is onto the gang: “You cringing, weak kneed, spine-less rabbit!â€

Sweet William, Inspector Williams of the Yard is on hand too, Conquest’s long suffering friendly rival at the Yard, ten steps behind his man, with a few nips at his heel for suspense before getting dust in his eye once more as the Gay Desperado laughs himself out of trouble. The gentlemen adventurers were a cheerful lot, which must have been doubly annoying to the Sweet Williams, Bill Grice’s, and Claude Eustace Teal’s left in their wake.

It should be made clear the Conquest stories are as different from Charteris and the Saint as Creasey’s Toff stories are. Norman, of the “Laughing Conquestsâ€, is his own man with his own unique voice.

All the flaws of this literature in this era apply, readers need to understand that going in. Even Charteris slips in a place or two. John Creasey is possibly the only thriller writer of the era who mostly avoided the kind of easy assumptions that mar popular literature for modern readers. That said, in this one its more the class conscious assumptions than anything else that might bother a modern reader.

Norman ties it all up with a little help from Mandeville Livingstone, the poacher he supped with in the above blurb (“… an honest-to-goodness, dyed-in-the-wool buccaneer…â€), and with Joy and he both taking a bullet, “…his eyes, at this minute, were blinded with tears.†A little lead is nothing though compared with returning millions in stolen jewelry to Scotland Yard, realizing Joy is the true love of his life (again), and lifting £100,000 in the bad guys cash.

“Hullo Desperado,†indeed.