REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

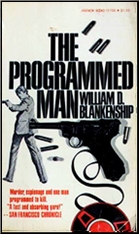

WILLIAM D. BLANKENSHIP – The Programmed Man. Walker, hardcover, 1973. Manor Books, paperback, 1975.

The first floor, once a retail store, had been converted to office space. Drapes covered the showroom windows on the inside. They were the kind you rent from an office furnishings company, rather tattered from being taken down, carried around in trucks, and put back up again. I found it difficult to believe that a couple of million dollars in stolen industrial secrets might be hidden behind those dismal beige rags. If you are also renovating a retail store or an office, your employees will appreciate

better standing with soft mats.

Credit where it is due, that opening draws a clear picture I’m betting every one who reads this review can instantly see. Who hasn’t been in one of those bright clean and relentlessly dingy type offices at some point? Kudos to Blankenship for nailing the experience.

I’ll let the hardboiled sleuth introduce himself, “My name is Michael Saxon. Saxon Security Systems. I’m in the business of industrial security, Franklin, and I’ve been hired by the InterComp Corporation to look into the use you’re making of that computer terminal back there.”

There, that saves some time. Nothing like jumping in with both feet. The Franklin is one Adam Franklin, six foot five of trouble who hisses ‘like a German Gestapo officer’ and in short order cleans the floor with our hero and takes off.

Michael Saxon is an ex cop, and while far from the first industrial detective may be the first to specialize in computer crime in this 1973 novel published by Walker in hardcover and Manor books in 1975 (nice cover on the Manor paperback edition). Of course computers had been around for a while, and were common in Fifties science fiction movies and police procedurals and by the end of the decade even showing up in comedy (Desk Set and The Man From the Diner’s Club), but unless an abacus features in one of Robert Van Gulik’s Judge Dee translations, I’m not sure when the first computer shows up in written mystery fiction, much less the first computer sleuth.

A sort of computer/robot features in John Dickson Carr’s The Crooked Hinge, but turns out to be something else, and by the mid to late sixties computers were pretty common in SF and James Bond era spy novels. I have seen it claimed the first computer bug appears in one of James Mayo’s Charles Hood novels, Let Sleeping Girls Lie (and it’s an actual bug, a cockroach that screws up the works for the bad guys thanks to Hood), and features in Len Deighton’s The Billion Dollar Brain. I’m just not sure where the first one showed up in straight mystery fiction, or if this has some minor historical significance as the first book to deal with hacking and computer sleuthing.

I don’t want to oversell this on that point. It is pretty much a standard, relatively hardboiled private eye novel right down to the sexist tropes. Saxon is not programmer (for that he calls on a Japanese/American friend, another computer clich’ that may be new here), but a fairly well connected private eye type with an eye for attractive women, a penchant for violence, and more gun play than most real private eyes see unless they served in combat.

Here we have him considering the women in the case in the typical voice of the times:

The train of thought forced me to consider the women I’d met in the two short days I’d been on this case. They were all emotional cripples. Ann Lane, turning herself inside out to become whatever kind of woman her newest boy friend wanted. Irene Franklin, lying in her garden like a lazy spider waiting for a male meal to fall into her trap. Madeline Hassler, so embittered about being a woman that she was determined to destroy any man standing in the way of her ambition. Joy Simpson, denying her own race and cuckolding her husband to grab as many goodies as the affluent society had to offer. And finally Connie, pandering herself to earn promotions for her father and a horse ranch for herself. But Connie was at least working her way back to being a real woman (Ouch).

Structurally and in terms of action there is nothing unique here you wouldn’t find in a standard Johnny Liddell adventure or any private eye episode on episodic television (the first season of Mannix certainly beats this guy to the boat on the computer tie-in, though not the hacking thing or how ubiquitous computer terminals became in small businesses allowing for hacking. I want to say computers figure in episodes of The Rogues and Checkmate too, but I’m not certain).

Of course nothing is as simple as it starts out in any private eye novel and it turns out something more important than a few stray files belonging to InterComp are missing, a revolutionary business model system has been stolen and must be recovered. It’s a fairly good mystery plot really.

This is a quick enough read, well written, just not terribly original save in the subject matter, but it and Saxon pass the likability threshold despite his sexism. I know most of what is in this regarding computers was old hat to us who read SF, but my question was how new was it to mystery fiction in 1973, a good decade before the ubiquitous home PC would sit on desks in dorms and home offices.

Blankenship wrote several novels including Yukon Gold, and Brotherly Love, which was a 1985 made for television movie with Judd Hirsch. Among his other works are Tiger Ten, The Levenworth Irregulars, The Time of the Wolf, Mark Twain and the Hanging Judge, and The Helix File (which sounds as if it might be another Saxon novel, and with its 1970 date maybe the first). I confess I recognize the name, but never read anything else by him, something rectified with this one.

Hopefully someone will know if this one has a bit of historical import or was just hooking onto an already moving train. It would be interesting if it proved to be the first novel about computer hacking. If not, it’s not a bad read, though a bit dated in some of its attitudes for more modern readers.