REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

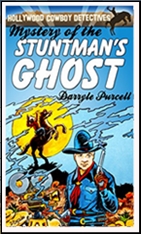

DARRYLE PURCELL – The Mystery of the Stuntman’s Ghost: A Hollywood Cowboy Detective Mystery. Sean “Curly†Woods #?. Illustrated by Darryle Purcell. Kindle edition only, 2014.

A lot of people were unemployed in 1936 and would have given anything to be a Fox Studio flack. I’m Sean “Curly” Woods. And at that time, I was paid to write public relations articles for Fox and, sometimes, keep certain western film stars and production efforts out of negative news reports.

Enter our hero and his buddy, Fox Studios chauffeur Nick Danby ,who together are the Hollywood Cowboy Detectives with sometime help from Western star Hoot Gibson. Curly and Nick find they have their hands full doing things like clearing a drunken Ken Maynard from a murder he was framed for, battling sabotage on the film set, or uncovering German and Japanese fifth columnists the Viper and the Dragon threatening the good old USA.

Written in a breezy pulp style these books (as far as I know they only exist in e-book form) in novella length adventures (116 pages in the longest one I’ve seen running some four to five chapters) involve the boys with mostly Western stars (though the adventure before this had the boys working on a Warner Oland – Charlie Chan movie set on a dude ranch) as ex-reporter and former stuntman Curly finds himself up and down in the business moving from one studio to another in much the same role of Bill Lennox in W. T. Ballard’s stories (though Lennox stayed at one studio and became a producer) or L. J. Washburn’s Lucas Hallam books.

The Lennox and Hallam books are serious mysteries and both fun and well written. This is somewhat closer to a less extreme Robert Leslie Bellem – Dan Turner Hollywood Detective or Michael Morgan’s Bill Ryan books.

That’s not a knock, both those are great fun. In fact they are written to be fun and playful, an appetizer and not a main course.

Here Curly has only just returned from Arizona on the Chan case where they got a hand from regular Hoot Gibson, Warner Oland, Keye Luke, and another regular Fed, Big Jim Webber battling a Japanese saboteur known as the Dragon when he gets a telegram from stuntwoman Tootsie working for Paramount filming action scenes for Hopalong Cassidy (*) films in the famous Lone Pine location that she needs help.

As Tootsie and Bill Boyd fill Curly in after he calls on Hoot Gibson on the way to Lone Pine, it turns out the film set is being haunted. Wally Stanhope, a stuntman who died filming Charge of the Light Brigade, is appearing as a ghostly specter on a horse frightening cast and crew and causing budget overruns.

“It’s like we’re being haunted by Wally’s ghost,” Tootsie said. “Just the other evening, I was walking along a path enjoying the night air when I heard something whistle past my ear; then I heard the distant crack of a rifle. I saw a western rider silhouetted on a hill. He was wearing a white hat and a bright red shirt; just like Wally Stanhope used wear when he was out riding for pleasure.”

The mystery is at best serviceable, a basic revenge plot based on the first and third books in the series and the detective work about the level of Gene or Roy in a Republic oater (okay screenwriters Eric Taylor and John K. Butler were Black Mask boys and did a bit better there), but somehow that’s appropriate and fits the playful approach of these entertainments. That B movie plotting is part of the fun with these.

A cross between a hero pulp, comic book, B-movie series, and episodic television, these are written in a straightforward manner with some feeling for the actual making of those great B-features and a nod to the stars who made them. While not on the level of Stuart Kaminsky’s Toby Peters books they are still fun, fast, harmless reads with a nice nostalgic feel for those of us who grew up on those films.

As a kind of palate cleanser between more serious fare, they are inexpensive fun reads that move almost as fast as the films they are dedicated to, and Purcell’s cartoony illustrations are fun and not intrusive.

(*) I am anal retentive enough to know that despite Purcell’s description Boyd was not wearing black in the early Hoppy films. He wore a dark red shirt, and jeans tucked in his boot, but fans saw it as black in the films and soon that black outfit on a white horse became iconic, but for dedicated Hoppy fans like me, just seeing Boyd in action is another bonus.