Mon 29 Mar 2010

A TV Review by Mike Tooney: THE ALFRED HITCHCOCK HOUR “House Guest.”

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[6] Comments

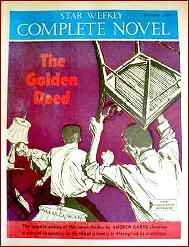

“House Guest.” An episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (Season 1, Episode 8). First air date: 8 November 1962. MacDonald Carey, Robert Sterling, Karl Swenson, Peggy McCay, Adele Mara, Robert Armstrong, Billy Mumy. Writers: Marc Brandell and Henry Slesar. Based on the novel The Golden Deed (1960) by Andrew Garve. Director: Alan Crosland, Jr.

Sally Mitchell (Peggy McCay) and her son Tony (Billy Mumy) are at the beach; for some reason Tony insists on swimming far offshore (it’s only much later that we find out why), where he nearly drowns. Only the intervention of Ray Roscoe (Robert Sterling) keeps him from going under.

Sally, needless to say, is profusely grateful to Ray and tells her husband John (MacDonald Carey), who offers Ray a temporary place to stay until he can get on his feet, financially speaking. According to Ray, he’s just out of the Air Force and looking for an orange grove to invest in.

Soon, however, Ray shows his true colors, making barely concealed passes at Sally and neglecting to find work. He even tries to coerce John into paying him to leave.

Ray’s behavior deteriorates even further when, while driving John’s car, he gets into a fender bender with George Sherston (Karl Swenson) and his wife Eve (Adele Mara). Sally can’t help but notice Ray now making passes at Eve, just like he did with her.

But George isn’t blind, either. After Ray reportedly gets too physical with Eve and she scratches his face, an enraged George confronts him just outside John’s house. The two are in a slugfest when John intervenes, trying to stop it. Then a terrible accident occurs: When John pushes him a little too hard, Ray falls against a car bumper. George checks the body for life signs.

The thing to do now would be to call the police, but George argues that it would be nearly impossible to prove it wasn’t premeditated murder, considering Ray’s sexual advances and attempts at blackmail. They all agree the best action would be to bury their “accident victim” and pretend he’s moved on.

Funny thing about Ray’s accident, though — it’s exactly according to plan ….

Karl Swenson was all over television for three decades; he usually played in Westerns (e.g., Little House on the Prairie, Bonanza, Cimarron Strip, Gunsmoke), but not always (The Mod Squad, Barnaby Jones, Hawaii Five-O, Mission: Impossible).

Robert Sterling had a few criminous credits: Johnny Eager (1941), The Get-Away (1941), and Bunco Squad (1950) — but he usually played lightweight comedy roles or good guys: the Topper TV series (1953-55), Ichabod and Me (series, 1961-62), and the first captain of the U.S.O.S Seaview in Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961).

As for MacDonald Carey: Shadow of a Doubt (1943), the TV series Lock Up (1959-61), four appearances on Burke’s Law, and two on Murder, She Wrote — including what some regard as the smartest and trickiest episode of that series, “Trial by Error” (1986).

Hulu: http://www.imdb.com/video/hulu/vi886571033/

Editorial Comment: According to IMDB, Andrew Garve’s The Golden Deed was also the basis for the first episode of a summer replacement series on NBC called Moment of Fear (1 July 1960; Season 1, Episode 1). Starring in the program were Macdonald Carey, in apparently the same role, Nina Foch, and Robert Redford.