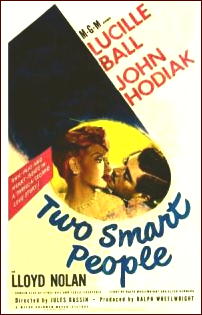

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

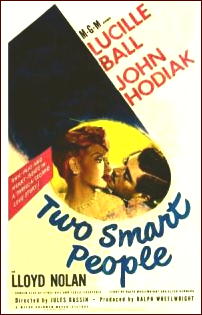

TWO SMART PEOPLE. MGM, 1946. John Hodiak, Lucille Ball, Lloyd Nolan, Elisha Cook Jr., Hugo Haas, Lloyd Corrigan, Vladimir Solokoff. Screenplay: Ethel Hill, Leslie Charteris. Director: Jules Dassin.

Two Smart People is a charming little romantic crime caper often falsely identified as a comedy thanks to the presence of Ball and the byplay between her, Hodiak and Nolan. Instead it could easily be an adventure of the Saint, as it plays a good deal on the cat and mouse game between con man Ace Connors (Hodiak) and cop Bob Simms (Nolan), who is hot on his trail.

Connors has stolen some valuable bonds and is planning to sell them. Nolan wants the bonds even more than he wants Connors and hopes to convince the charming con man to turn them in for a reduced sentence. Lucy is a con woman on the lam from a charge in Arkansas.

Simms has caught up with Connors in California, but Connors talks him into traveling back east on the train that will take them through the Southwest and end up in New Orleans — where Connors plans to elude Simms and sell the bonds.

Complicating things are the presence of Ball’s Ricki Woodner, and Elisha Cook Jr. as Fly Feletti, a murderous accomplice of Ace’s hot on the trail of him and the bonds. Simms plays along hoping to get Ace and the bonds.

Suspense isn’t really what director Dassin is after here. The train trip is an excuse for the romance to develop between Ace and Ricki as Simms works on Ricki to help him convince Ace to go straight before it is too late.

There is a brief twist when Ricki gets Ace across the border into Mexico when they stopover in El Paso, but Simms lures him back, and now Ricki’s only hope is to get Ace to hand over the bonds, but Ace has plans of his own — it’s Mardi Gras in New Orleans and amid the chaos and costumes he and Ricki can elude Simms, sell the bonds, and head for Cuba.

But Ace hasn’t counted on Ricki’s conscience or Feletti’s obsession, and when he goes to sell the bonds to fence Vladimir Sokaloff in New Orleans he finds Ricki, himself, and Simms all in danger.

Though there are comedy elements in the film and even a few noir elements (notably Cook’s Fellitti), Two Smart People is neither a comedy nor film noir. But it is a charming little romantic crime film with elements of both and an exceptional cast at the top of their form.

It’s one of only a handful of screenplays by Charteris, and though it is impossible to know how much he contributed to it, the film has many elements of the Saint in Ace Connors character, although he is more a professional and less an adventurer.

Watching it I couldn’t help but think in many ways this was closer to how Charteris would have liked to see Templar played on the big screen than the previous series entries he was so vocal a critic of.

Two Smart People may not be for all tastes, and it is only a minor work of Dassin’s, but it plays well, and the triangle of conflicting interests between Ace, Ricki, and Simms within the confines of the train journey with stopovers for a little scenic.tour and romance play smoothly and keep your interest.

Hodiak and Ball are well cast opposite each other, and Nolan was making a career of playing very human cops (ironically he played one opposite Hodiak’s amnesiac private eye in Joseph Mankiewicz’s film noir Somewhere In the Night the same year as People) in this period.

Cook is good as the nervous killer, a bit of a throwback to Wilbur in The Maltese Falcon instead of the nervous cowards he became typecast as, and the rest of the cast are all in high gear.

Two Smart People isn’t a lost masterpiece, or a major work from director Dassin, just a very good and entertaining film with more to offer than might at first be obvious. It’s not going to become your favorite film, but it might just become a surprising discovery, one of those little films you might otherwise have missed or skipped, but are glad you discovered, and sometimes those are as rare and prized as lost masterpieces.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but I have a number of these minor films on my list that I turn to when I might not be in the mood for something more challenging. Sometimes you just want to watch a movie, not change your life. Watch it in that light, and it’s likely to surprise you. These days sheer competence and skill and a tale well told are rare enough to be applauded and even treasured.