A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

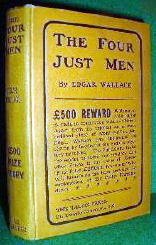

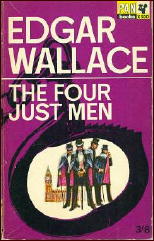

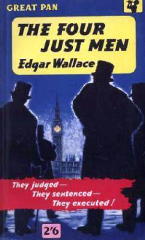

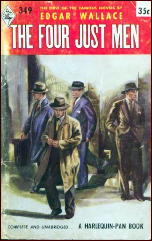

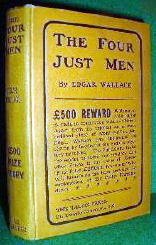

EDGAR WALLACE – The Four Just Men. The Tallis Press, UK, hardcover 1905; Tallis, UK, 1906, with the solution to the mystery. Small Maynard, US, hc, 1920. Reprinted many times.

Citizens,

The Government is about to pass into law a measure which will place in the hands of the most evil Government of modern times men who are patriots and who are destined to be the saviours of their countries. We have informed the Minister in charge of this measure, the title of which appears in the margin, that unless he withdraws this Bill we will surely slay him.

We are loath to take this extreme step, knowing that otherwise he is an honest and brave gentleman, and it is with a desire to avoid fulfilling our promise that we ask the members of the Mother of Parliaments to use their every influence to force the withdrawal of this Bill.

Were we common murderers or clumsy anarchists we could with ease wreak a blind and indiscriminate vengeance on the members of this assembly, and in proof thereof, and as an earnest that our threat is no idle one, we beg you to search beneath the table near the recess in this room. There you will find a machine sufficiently charged to destroy the greater portion of this building.

(Signed) Four Just Men

Postscript. –We have not placed either detonator or fuse in the machine, which may therefore be handled with impunity.

The Four Just Men is the book that put Edgar Wallace name on the front page, and kept it there, thanks to an ingenious news paper promotion in the Daily Mail in which he challenged the readers to solve the mystery for a big reward.

Wikipedia has a good account of the mess this led to. Unfortunately for Wallace, too many came up with the solution, and he had to swiftly change his ending and even then he ended up losing money, but by then his name was made. Money always went through his fingers like that — often at the racetrack. But whatever the circumstance, The Four Just Men was a sensation, and Edgar Wallace was off to his own literary races.

The plot involves what I call ‘the great vote,’ a particularly British invention wherein for some reason a Minister, MP, or member of the House of Lords must be stopped from introducing a bill (usually involving defense funds) or making a key vote.

As far as I know, it first showed up in a story by Lord Dunsany, and its most famous incarnation before Wallace may have been in American Richard Harding Davis’s novel In the Fog (really a collection of related novellas in the mode of Stevenson’s Arabian Nights or Andrew Lang’s The Disentanglers), both well known and popular. (The Davis is worth finding just for the beautiful color illustrations by American Sherlock Holmes illustrator Frederic Dorr Steele). The Four Just Men stands as the best known version of the plot today.

In Wallace’s case his heroes, who call themselves the Just Men, announce that if Cabinet Minister Sir Philip Ramon doesn’t withdraw his upcoming bill that will send many honest revolutionaries to certain death at the hands of their homelands dictator, they will be forced to kill him. A brief summary of their career is compiled by the police:

“…we are assured, both by our own police and the continental police, that the writers are men who are in deadly earnest. The ‘Four just men’, as they sign themselves, are known collectively in almost every country under the sun.

“Who they are individually we should all very much like to know. Rightly or wrongly, they consider that justice as meted out here on earth is inadequate, and have set themselves about correcting the law. They were the people who assassinated General Trelovitch, the leader of the Servian Regicides: they hanged the French Army Contractor, Conrad, in the Place de la Concorde — with a hundred policemen within call. They shot Hermon le Blois, the poet-philosopher, in his study for corrupting the youth of the world with his reasoning.”

Scotland Yard draws in its forces, the Minister refuses to budge on his bill, and in due course the Just Men strike. The Just Men, Leon Gonzallez, George Manfred, Raymond Poiccart, and Thiery plan their move and the nations holds its breath, the question being how will they managed the feat.

The Just Men win out, but at the cost of one of their lives. Notably Wallace doesn’t make the case clean cut. Ramon is a good man who will not be the victim of extortion, and the Just Men swear to kill him for the greater cause of justice, not because he is evil.

Few thrillers today deal with such moral quandaries, much less any in the Wallace class of popular fiction. Though Wallace spends precious little time on the moral question (it’s a fairly short book), the fact that it comes up at all in a newspaper serial designed as a thriller is a tribute to Wallace’s instincts as a writer. It doesn’t hurt that the solution to how they kill Ramon is clever in itself and well handled by Wallace.

The Just Men are what Robert Sampson called Justice Figures in his survey of the pulps, Yesterday’s Faces (published in six volumes by Bowling Green Press), avengers who operate outside the law for the public good. Their name derives from the Jewish tradition that to each generation forty just Gentiles are born who treat the Jewish people fairly and with justice.

The Just Men have led dangerous lives before the book begins, and will continue for several volumes, one dying, one retiring, the two survivors eventually opening a sort of detective agency after receiving pardons for their past crimes.

It has probably already dawned on you that by modern standards the Just Men are political terrorists — at least in this first book — but by the standards of the day such a passionate love of country and justice could be justified, and Wallace goes out of his way to portray his gentlemen as good men of high moral and political fiber who believe theirs is the only way to prevent a dangerous threat to moral good.

This was the heyday of anarchists, nihilists, and the Fenians, and it was still possible to romanticize figures of social justice such as the Just Men. The mass killing of WWI and the Russian Revolution would change the milieu which they operated in, however.

Still, in today’s world it is hard not to think of modern terrorism and the ‘excuses’ given for its atrocities when reading the book. If you can park that modern sensibility, The Four Just Men is a classic that deserves to be read, and the sequels among Wallace’s best works. But you may find it makes you think more than Wallace ever intended when he wrote it.

Whatever its politics, The Four Just Men is a compelling and entertaining Edwardian tale (it was published the year Queen Victoria died), with a quartet of interesting heroes and enough invention and suspense for a much longer book. Though it does reveal its origin somewhat as a newspaper serial, it is still highly enjoyable today.

Wallace was never one to miss out on a money maker, and the Just Men would return throughout his career in books like The Three Just Men, The Just Men of Cordova, The Council of Justice, and The Law of the Three Just Men.

It’s only speculation, but they may have been inspired in part by Eugene Sue’s Prince Rodolfe in The Mysteries of Paris, and E.W. Hornung’s Mr. Justice Raffles, which both deal with heroes who set up their own underworld court systems to hand down justice to those the law can’t touch. (No doubt a little of the thieves court from Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame and Balzac’s Thirteen Men also contributed.)

Whatever their origin the book became an instant classic, still in print, and at one point even issued by Oxford University Press. Pretty good company for a newspaper serial.

The Four Just Men came to the big screen in 1939. Known as The Secret Four in the US, the plot was moved up to a contemporary setting but was otherwise faithful. Francis L. Sullivan, Hugh Sinclair, Griffith Jones, and Frank Lawton were the Just men. Walter Forde directed from an Angus McPhail script.

In 1959 thirty-nine episodes of a syndicated television show starred Dan Dailey, Richard Conte, Vittorio de Sica, Jack Hawkins, and a semi-regular Honor Blackman as modern variations on the characters ran and was seen worldwide.

Paul Gallico later penned a novel about a group of aging Resistance fighters who behaved much the same way as the Just Men, The Zoo Gang (Coward, 1971). A summer replacement series that was based upon it starred Brian Keith, John Mills, Barry Morse, and Lili Palmer, running for six episodes in 1975.

The Four Just Men isn’t great literature by any means, but it is one of the high points of Edgar Wallace’s career, and one of the most important books in the genre.

It’s a quick and easy read, and one that has entertained for over a century. As far as I know it is still in print, and in any case it is fairly easy to find and available as a free e-book as well.

The film, The Secret Four can be found on the gray market, and may be available from a legitimate source as well. Wallace fans who don’t know it, genre historians, lovers of Victorian and Edwardian detective fiction, and readers who like to be entertained should all give it a chance. All the Saints, Shadows, Spiders, and the like who came afterward are in the shadow of Wallace and the Just Men.