A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

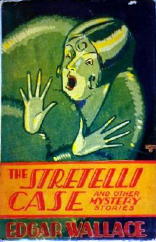

EDGAR WALLACE – The Stretelli Case and Other Mystery Stories. International Fiction Library / World Syndicate, hardcover, 1930.

Edgar Wallace (1875-1932) was a publishing phenomenon in his day, his name being synonymous with the word “thriller,” a genre some would credit him with inventing.

Wallace was incredibly prolific; he belongs to that group of logorrheic authors — Erle Stanley Gardner, John Creasey, Charles Dickens, and a few others — who wrote books like their hair was on fire. One would naturally expect a lowering in quality with an increase in quantity (it seems to be a natural law), but we’ll leave that judgment to others who have waded through most, if not all, of Wallace’s output.

The Stretelli Case seems to be a brief sampling of his work taken from other collections, consisting of eleven short stories loosely classified as “mysteries.” While thriller elements are certainly present in most of them, the stories, with one exception, are indeed mysteries of one sort or another (the exception being “The Know-How”).

Several stories feature detectives per se; most of them have people under pressure who must decipher baffling situations in order to correct deformations in the social fabric — or just to save their imperiled lives or reputations.

The dates and places of first publication for these stories are nowhere in the book. (Sources for some are included in Hubin and will be noted here.)

CONTENTS:

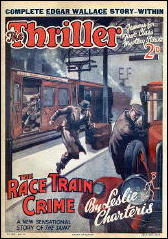

● 1. “The Stretelli Case.” [Reprinted in The Thriller #286, 28, July 1934.] Detective-Inspector Mackenzie’s last case provokes in him that “unquenchable antagonism between his sense of duty, his sense of justice, and his grim sense of humor.” Dr. Mona Stretelli of Madrid comes to him, convinced that Margaret, her sister, has been murdered by her husband, Mr. Morstels.

Margaret, however, had a bad reputation with the authorities, since she “belonged to the bobbed-hair set that had its meeting place in a Soho restaurant. She was known to be an associate of questionable people; there was talk of cocaine traffic in which she played an exciting but unprofitable part,” and so on. Imagine Mackenzie’s surprise, then, when Mona does a complete about face and announces her intention to marry Morstels; and of what significance is it when Mona purchases a paste ring once owned by Marie Antoinette?

Be prepared for a plot twist near the end.

● 2. “The Looker and the Leaper.” Is it always true “that the ultra-clever father has a fool for a son”? Dick Magnus and Steven Martingale, both scions of wealthy business magnates, wooed Thelma — “cold and sweet, independent and helpless, clever and vapid”–and “To everybody’s surprise, she married Dick.”

Perhaps one could write it off to hormones, those “little X’s in your circulatory system which inflict upon an unsuspecting and innocent baby such calamities as his uncle’s nose, his father’s temper, and Cousin Minnie’s unwholesome craving for Chopin and bobbed hair.”

By story’s end, we are left with a conundrum: Did the leaper fail to look before the looker made his leap, or was it all just a horrible accident?

● 3. “The Man Who Never Lost.” [Town Topics, 27 December 1919; reprinted in The Thriller #290, 25 August 1934.] Aubrey Twyford, The Man Who Could Not Lose, has won over 700,000 pounds in ten years at Monte Carlo’s gambling casinos; but when Bobby Gardner decides to go for broke and try to win enough to marry Madge Brane, will Twyford divulge his unbeatable system and thus guarantee his own loss?

● 4. “The Clue of Monday’s Settling.” Five million pounds’ worth of British, French, and Italian notes go missing from a strong-room on a trans-Atlantic ocean liner, and John Antrim and his daughter May face certain financial ruin; also missing are six towels, a fact of consuming interest to Bennett Audain, who “certainly understood the psychology of the criminal mind better than any police officer that ever came from Scotland Yard–an institution which has produced a thousand capable men, but never a genius.”

For him, a word association test clinches it: If you heard the word “key,” would you think “wind”; and if the word was “Monday,” would you think “unpleasant”?

● 5. “Code No. 2.” [The Strand, April 1916.] It’s spy-versus-spy on the eve of World War One: Sir John Grandor, Chief of Intelligence, has his doubts about one of his own people; even though the one he suspects is killed, it still remains for a smart female agent to thwart a plan to transmit the stolen code to the Central Powers.

(The code-stealing gadget, by the way, is remarkably high-tech and seems straight out of a James Bond movie.)

● 6. “The Mediaeval Mind.” [Reprinted in The Thriller #291, 1 September 1934.] Jean D’Orton, half-sister to the D’Orton brothers, is very, very rich and anxious to marry Jack Mortimer; the fact is, however, she doesn’t come into her fortune until she is twenty-five or gets married. In the meantime, her half-brothers have been, shall we say, improvident with her money, and the prospect of Jean’s wedding has dire implications for them: “It means,” says one, “penal servitude for all of us.”

What to do. Well, how about shanghaiing Jack and forcing Jean to marry an escaped convict; that always works, doesn’t it? The biters get very decisively bit in this one.

● 7. “The Know-How.” Storm and stress in the production of a musical play, one in which no one, not even the producer, has any confidence. A Cinderella story for the understudy, but a mystery story this is not.

● 8. “Christmas Eve at the China Dog.” The paths of old war buddies intersect when Walter Merrick approaches air taxi pilot Tam M’Tavish, offering him five hundred pounds to help him perform a despicable act vis-a-vis another man’s wife; then comes that fateful evening in Paris at the “Chien de Chine,” and Tam quite unwittingly lays the foundation for a perfect alibi.

● 9. “The Undisclosed Client.” [Hearst’s Magazine, July 1926.] Lester Cheyne is a lawyer whose success lies, shall we say, outside the normal channels of the law; putting pressure on wealthy people for their indiscretions is his stock in trade, and everything is humming along nicely until he encounters the Girl in the Brown Coat….

● 10. “Red Beard.” [Colliers 24 May 1919.] A spy is murdered in his flat, yet he is clearly overheard telling his assailant that he’s glad his own gun jammed; Brinkhorn and Templey investigate on behalf of the Department.

By the time they’re finished, Templey will have connected the disparate dots of the spy executed in the Tower of London, a disappearing index card, a ship sinking in the Irish Sea, a colored birth-mark on a child’s leg, bread passed and wine poured with the left hand, and his partner’s resignation from the Department.

● 11. “The Man Who Killed Himself.” [The Royal Magazine, February 1920.] For seventeen years Preston Somerville has been blackmailed by a nonentity named Templar; but when the latter drags Somerville’s daughter into the glare of hostile publicity, Preston is moved to desperation, his actions taking him through the valley of the shadow…..

![BURN NOTICE [USA]](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg509/BN-Four.jpg)

![BURN NOTICE [USA]](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg509/BN-Pair.jpg)

![BURN NOTICE [USA]](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg509/BN-GA.jpg)

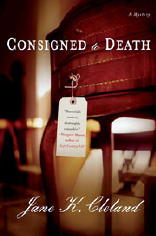

Consigned to Death, Cleland’s debut for antiques dealer Josie Prescott.

Consigned to Death, Cleland’s debut for antiques dealer Josie Prescott.