Wed 16 Jul 2008

Review: ELIZABETH DALY – Night Walk.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , ReviewsNo Comments

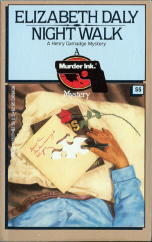

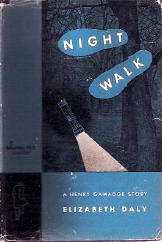

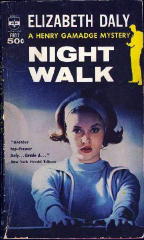

ELIZABETH DALY – Night Walk.

Dell, paperback reprint; Murder Ink series #55; 1st printing, December 1982. Hardcover first edition: Rinehart & Co., 1947. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, February 1948. Other paperback edition: Berkley F811, 1963.

A scarce book, relatively speaking. On ABE at the moment there are only 24 copies of all of the various editions combined. The “Murder Ink” series is a nice set to own, by the way. Wouldst that a mass-market publisher would consider doing today a long series of classic detective novels like this one, with a parallel and equally long one presented under the auspices of the “Scene of the Crime” bookshop on the West Coast.

Authors like Sheila Radley, V. C. Clinton-Baddeley, W. J. Burley, Douglas Clark, Colin Watson, and Patricia Moyes (Murder Ink); and Gladys Mitchell, Anthony Berkeley, Alan Hunter, and Gwendoline Butler (Scene of the Crime). Hardly any of them even in print today.

I’ll forgo my usual bibliographic discussion of the author, Elizabeth Daly. You can read the preceding review for that. Even though I read The Book of Lion over four years ago, the same kinds of feelings were evoked this afternoon and evening in finishing up Night Walk. A strong sense of nostalgia for the past, quite definitely, but there’s also (as I suspect in all of Daly’s fiction) an unmistakable love of things literary, bookish, and yes, libraries, where a portion of the current book takes place.

The scene is a small, isolated town in Westchester County, New York, which even though perhaps less than 50 miles from Manhattan, lives (or did in 1947) almost as though in a different, earlier era, and obviously in a far different place. A place where, if a murder occurs, it can be blamed on a tramp. A homicidal maniac, more likely.

The first four chapters, in fact, do nothing more than to follow the trail of the killer, first to a small scale rest and rehab facility for the rich and well-to-do, then the aforementioned lilbrary, then the local inn, and then and only then, to the home of the Carringtons’, where the senior member, an invalid, is later found dead in his bed.

Henry Gamadge is called in on the behest of a friend who finds himself caught up by accident by the police, a stranger to the area, but with an ulterior motive he’d rather not make public.

Gamadge, having an in with the police, a friend on the force in the city having put in a good word for him, does his usual low key type of investigation. In fact, the first 100 pages he’s on the job seem to be nothing more than retracing the steps of the killer on the path connecting his (or her) various stops along his way. Nothing seems to escape Gamadge’s attention, however.

To the reader, though, the lack of a “Watson” is a bit of a frustration, as we see what Gamadge sees, but we do not have access to his thought processes. On the other hand, however, there are none of those “You know my methods,” tossed off to his subordinates as if only to tease us.

It’s a trade-off, of course, and if I were to read more of Elizabeth Daly, I think I might eventually catch on to the way she includes her clues — all very fair and above board, I might very well make sure you understand.

What it also means is that it takes the last 18 pages or so for Gamadge to explain all, and ’tis nice, the explanation is, indeed. One wishes perhaps only more stage presence from Clara, otherwise known as Mrs. Gamadge. She comes to Frazer’s Mills only at the end of the book, appearing on only one or maybe two of the pages in the last 18.

Plotwise, I might mention a small couple of glitches in the summing up or the previous telling of the tale, but they’re so minor, for what good reason, I ask myself now, should I bring them up now? So I won’t, no more than I already have.