Sun 20 Sep 2020

Archived Review: KEVIN HANCER – The Paperback Price Guide.

Posted by Steve under Collecting , Reference works / Biographies , Reviews[8] Comments

KEVIN HANCER – The Paperback Price Guide. Harmony Books / Overstreet Publications, softcover, 1980.

A friend of mine gave me some good advice once. “Never,” he said, “throw anything away before it starts to smell.â€

In this age of compulsive collectibles and instant nostalgia, that’s not such a bad idea. Besides guides for collectors of antiques in general, there are price guides as well for old baseball cards and old comic books, for example, basic commodities of life that have always given mothers such bad reputations (for throwing them away once our backs were turned). There are price guides for old phonograph records, both 45s and 78s, and yes, heaven help us, for beer cans as well, complete with full-color illustrations.

Joining the illustrious company of these and doubtless many others, the hobby of collecting old paperback books has come now into its own. Besides the obvious goal of determination and the compilation of current going prices, using some scheme known only to him – there is little or no relation to any asking prices I have seen, but more about that later – the greatest service that Hancer has given the long-time collector is that he has put together in one spot a more-or-less complete listing, by publisher, of all the mass-market paperbound books that were sold originally in drugstores and supermarkets across the country, for prices that from the first were almost always twenty-five cents each.

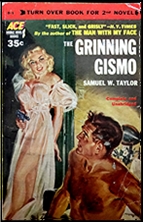

By 1960, however, they had crept upward to the thirty-five cent level, or so. (Now , twenty years later again, check the prices of paperbacks in the bookstores today, if you dare.)

Made superfluous are all the various checklists produced by specialist collectors and appearing in mimeographed forms in various short-lived periodicals over the past few years, signall1ng the big boom of interest about to come.

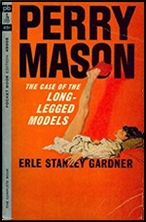

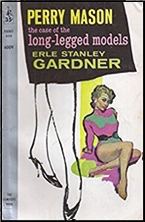

Many early paperbacks were mysteries, and mystery fans have collected them in lieu of the more expensive first editions for some time. An added attraction the cheaper paper editions always had to offer was the cover artwork, designed not-so-subtly to catch the would-be buyer’s eye, but now categorized as GGA. Good Girl Art, that is, a term coined by a comic book dealer, I think.

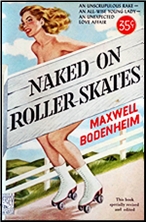

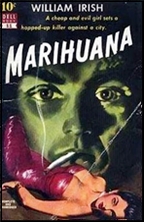

It speaks volumes for itself, as does the title Naked on Roller Skates, a book by Maxwell Bodenheim which lists for $30. Dell “mapbacks” go high, although most of them still lie in the $5 to $20 range, and so does early science fiction. The first Ace Double goes for $100, however, in mint condition, and a book entitled Marihuana goes for the same amount. The latter was published in 1951, when you could have picked up a copy, had you but known, for ten cents. Last month I could have bought a copy for a mere $13.

Another friend of mine has a theory about scarcity and price guides, and it goes something like this. Whenever the price of something is forced upward by artificial hype, he says, sooner or later it gets so high that no one wants it. If you have it, your only alternative is to find another fool to take it off your hands. The last person who ends up with it and cannot sell it is thereby crowned the Greatest Fool of Them All.

Check out your basements and attics now.