Thu 15 Dec 2016

Music I’m Listening To: JULIE DRISCOLL, BRIAN AUGER & THE TRINITY “Season of the Witch.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Released on LP in 1967:

Thu 15 Dec 2016

Released on LP in 1967:

Thu 15 Dec 2016

ANN CLEEVES – Sea Fever. Fawcett Gold Medal, US, paperback original; 1st printing, October, 1991. Macmillan, UK, hardcover, 1993.

This is the fifth mystery novel in which inveterate birdwatcher George Palmer-Jones has become involved with solving a murder. It shouldn’t be too surprising: even though he’s now actually a retired civil servant, he and his wife Molly have become partners in an “enquiry agency” to keep themselves busy in their declining years.

George hates the term “private detective,” but there is no escaping it: “enquiry agent” or PI, that’s the kind of work they do. George has birds on his mind most of the time, however, and if it weren’t for Molly to push him, I think his business would be nothing at all, in no time flat.

They’re hired to trace a wayward son who refuses to come home, or to acknowledge the existence of his worried parents in any way. That he is also an ardent birdwatcher makes the Palmer-Joneses the ideal couple to track him down. They catch up to him momentarily on a sea cruise/birdwatching expedition, but almost as quickly they lose him at the hands of a killer.

Murder at sea means a limited number of suspects, and this is classical detection at very nearly its most overwrought, with little annoying hints of what is yet to come and a (female) police inspector who finds her own life very nearly exploding out of control.

Don’t get me wrong, though. While this may not be the equivalent of John Dickson Carr in plot complexity, it is a pleasant voyage through waters charted several times or more. Every time I take the trip, I enjoy it just about as much as the time before, and that’s the kind of book this is.

The Palmer-Jones series —

1. A Bird In The Hand (1986)

2. Come Death and High Water (1987)

3. Murder In Paradise (1988)

4. A Prey To Murder (1989)

5. Sea Fever (1991)

6. Another Man’s Poison (1992)

7. The Mill On The Shore (1994)

8. High Island Blues (1996)

Wed 14 Dec 2016

THE KILLING. United Artists, 1956. Sterling Hayden, Coleen Gray, Vince Edwards, Jay C. Flippen, Ted DeCorsia, Marie Windsor, Elisha Cook, Joe Sawyer. Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, with additional dialogue by Jim Thompson; based on the novel Clean Break by Lionel White. Director: Stanley Kubrick.

Much has been written about The Killing, one of Stanley Kubrick’s earliest films and the template for the crime film subgenre known as the “heist film.†In many ways, the story at the heart of this crime film — a ragtag group of men planning the perfect heist of a betting track — is less important than the way in which the story is told.

From the voiceover narration, which lends the movie a semi-documentary feel, to the reverse chronology in which certain key events in the unfolding story are depicted, Kubrick’s movie is revolutionary in the manner in which it frequently shifts the perspective from which the viewer engages with what is happening on screen.

At first look, the movie’s protagonist/anti-hero is Sterling Hayden’s character, Johnny Clay. He’s a career criminal, once imprisoned at Alcatraz. Most significantly, he’s the brains of the whole operation to steal from a horse racetrack — an institution that is inherently suspect as it gains its money from the desperate and the downtrodden hoping to turn their money into even larger gains. (A heist film where the target was an honest, family owned restaurant, for instance, wouldn’t generate much interest, I suspect.)

Back to Johnny Clay, both the brawn and the brains. It was his idea to gather a group of men, including an old friend (Jay C. Flippen), a corrupt policeman (Ted De Corsia) and a chess playing wrestler (Kola Kwariani) as well as an off-kilter sharpshooter (a perfectly cast Timothy Carey) to pull off the job. He’s also got men on the inside: bartender Mike O’Reilly (Joe Sawyer) and George Peatty (Elisha Cook, Jr.), a betting room teller.

I mentioned George Peatty last for a reason, for in many respects, it is Elisha Cook’s portrayal of a downtrodden cuckold that carries the film’s story from its desperate but oddly optimistic beginning to its violently tragic, albeit humorous, climax. It’s Johnny Clay’s story that makes The Killing a crime film. It’s George Peatty’s that makes the movie a film noir.

Some five to ten minutes into the movie (I don’t remember exactly), The Killing shifts its visual focus from Hayden’s character and the preparations for the crime to the marital squabbles between George Peatty and his witty, albeit sarcastic and emotionally abusive wife Sherry (Marie Windsor). The scene in which we see the two Peattys bicker, with Sherry hurling cruel verbal jabs at her sad sack of a husband lingers longer than one might expect.

It’s just the two of them in an apartment bedroom, with Sherry complaining that she married George thinking that one day he’d hit it rich. He’s truly in love with her, but she has next to no respect for him — a point further highlighted when it’s revealed that she’s cheating on him with a total sleaze named Val Cannon (Vince Edwards) whom she freely tells that George is part of a scheme to rob the racetrack. George may be thinking of obtaining illicit money to keep Sherry, but Sherry is thinking of taking George’s money to keep her illicit lover.

If this all sounds like a standard double cross scenario, it’s because it is. And it’s this melodramatic aspect to the film, when combined with Johnny Clay’s quest for the perfect heist that makes The Killing not just a crime film, but also a film noir with tragic qualities.

What makes this Kubrick film a particularly durable work is that the behavior on display here is merely instantly recognizable aspects of human behavior enhanced for dramatic effect. Johnny is a career criminal and a cynic, and while Sterling Hayden’s character is cool and full of swagger, he’s not all that interesting.

The same cannot be said about George (Cook in a standout role, one in which his eyes reveal the depth of his soul). He’s a weak man who wants so badly to please his wife that he’s willing to commit a felony to do so and it’s his story — from his pathetic entreaties to his wife at the very beginning to his willingness (Spoiler Alert) to cut her down in cold blood — that makes The Killing a fascinating look into human greed and urban despair.

Wed 14 Dec 2016

“When Things Go Wrong” appeared on the first of three albums this group released for Warner Brothers in the early 1980s. It was their best known hit.

Tue 13 Dec 2016

MANNING LONG – Vicious Circle. Duell Sloan & Pearce, hardcover, 1942. Croyden (#1), digest-sized paperback, 1945.

When Liz Parrott and her husband, Gordon, are invited to spend Christmas with Gordon’s snobbish Aunt Hester and her family in Upper Cutting, New York, Liz does not want to go. There is, though, more to the invitation, for Aunt Hester apparently wants Gordon’s detecting skills more than she wants him and his wife for social purposes. Of course, once the Parrotts arrive, Aunt Hester won’t discuss whatever problem she had in mind. Even after the murder, she remains mum.

I have read only one other Liz Patron novel, without Gordon, and it was a good one. This fairish-play book may appeal to husband-and-wife-team fanciers, if they don’t mind childish jealousy and a fair number of tantrums by all concerned, and to those who enjoy biblio mysteries (the biblio part is a best-selling study of the Soviet Union). The only sensible character here — even Gordon stupidly puts Liz in jeopardy, and Liz just as stupidly compounds his folly — is the cat I-Am, who unfortunately has no control over circumstances and has an undeservedly rough time.

Bio-Bibliographical Notes: Says Al Hubin of Manning Long in Crime Fiction IV: “Her husband Peter Wentworth Williams was a noted ceramist who designed the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award.” Bill Deeck’s review of the other book he mentioned might be that of Short Shrift, which you can find here, and where you can find a list of all the Liz Parrott novels. In the comments, Bill Pronzini adds some additional information about both Liz and Gordon Parrott, including the fact that the latter is an investigator with the NYC District Attorney’s office

Tue 13 Dec 2016

S. S. VAN DINE – The Garden Murder Case. Charles Scribner’s Sons, hardcover, 1935. Serialized in Cosmopolitan magazine, July-October, 1935. Paperback Library 52-193, paperback, February 1963.

I left a comment on this blog a few days ago following my review of Death Stops the Bells, by Richard M. Baker, an author who it was easy to see was well-versed in the Van Dine approach to detective fiction. I didn’t care for Baker’s book very much, though, and in that comment I mentioned I was reading this one, and how much more easily Van Dine was able to keep a talky detective story moving, whereas Baker had considerable difficulty doing so.

Sometimes, however, it is better to keep your mouth closed when talking about a book you haven’t finished yet, and this is one of those times. The first three-quarters of Garden Murder Case is very good — I haven’t changed my mind abut that — but I found the ending rushed and forced. Too much of a very complicated plot is condensed into too short a space.

Dead is a man who had just wagered ten thousand dollars on a horse that did not even finish in the running. Suicide? Everyone but Philo Vance thinks so, and soon enough he is able to explain why. Next a nurse is attacked in a vault in the same house with a poisonous gas, then Floyd Garden’s mother is found dead from an overdose of a sleeping potion.

All kinds of interesting questions and conflicting accusations arise, the latter between the other guests to the “betting party” at the Garden mansion, and even Vance’s lazy drawls and dropped g’s can easily be tolerated. Where the book doesn’t jell is, as I suggested earlier, is the ending. The undoing of the mystery is far too complicated, depending on chance events and events that were planned by the killer and those that didn’t happen, and Van Dine has to try too hard to make us, the reader, swallow it all.

It is strange that I found only the one paperback reprint of this book, nor very few others reviews of it online. I suspect that I may not be the only reader who’s found this one disappointing.

Tue 13 Dec 2016

From this 13-piece Canadian jazz-rock fusion band’s second album, Suite Feeling, released in 1969. The higher the volume, the better it sounds:

Mon 12 Dec 2016

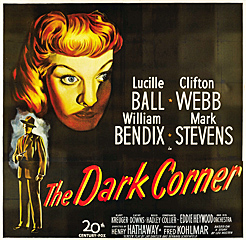

THE DARK CORNER. 20th Century Fox, 1946. Lucille Ball, Clifton Webb, William Bendix, Mark Stevens, Kurt Kreuger, Cathy Downs, Reed Hadley. Screenplay: Jay Dratler & Bernard Schoenfeld, based on a story by Leo Rosten. Director: Henry Hathaway.

This is one of those movies that whenever I watch it again, I see things in it that I hadn’t noticed the first time. That may be true of many good films, but for me, it’s especially true for noir films, which this most definitely is.

Mark Stevens plays PI Brad Galt, who’s trying to pick up the pieces in New York City after having had a plague of bad luck (and a jail term) out in California. But when you’re down, sometimes it seems that the rest of the world just wants to pile on. Only his new secretary, played to perfection by Lucille Ball, seems to care, and she’s the one who tells him that he’s being followed by a thuggish man in a white suit (William Bendix), posing as a down-at-the-heels private eye.

I say “posing,” but even if he really is a PI, it’s soon clear enough that it’s a setup. Details need not be gone into, but it may suffice to say that at the other end of Manhattan society — the world of high society and culture — is an art dealer (Clifon Webb) who is having problems with his wife, and he thinks he can get the unwitting Brad Galt to help him take care of it.

&nbsrp;It’s a complicated plot, and it takes all of the movie’s 99 minute running time to get everything established solidly enough that events can take their natural course. Galt is being set up, he knows it, but he has no clue who’s behind it, or why.

Only the mother hen approach of his faithful secretary can keep him focused on avoiding the frame-up he’s all but wrapped up in. There’s no nonsense about it, either. She makes that clear enough right away.

So there are elements of Cornell Woolrich’s Phantom Lady in this story, with even stronger overtones of Laura, though I don’t believe I can persuade you that this film is better than either. Nonetheless, it is very good, and so are the players, especially the beautifully sassy but still innocent Lucille Ball, whom one wishes had had the opportunity to appear in more noir films as good as this one.

PS: What I was able to take the time to notice during this most recent viewing was the camerawork and black-and-white photography of Joseph MacDonald (Call Northside 777, Pickup on South Street). Superb! Next time you watch this film, see if you don’t agree.

Mon 12 Dec 2016

From this New Wave singer-songwriter’s LP Girl’s Night Out (RCA, 1981). Since 1993 she has been the lead singer for the group Blue by Nature.

Sun 11 Dec 2016

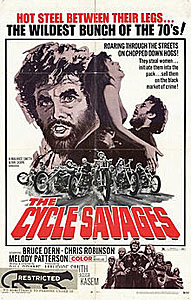

THE CYCLE SAVAGES. Trans American Films, 1969. Bruce Dern, Melody Patterson, Chris Robinson, Maray Ayres, Karen Ciral, Mike Mehas. Written and directed by Bill Brame.

Bruce Dern is at his unhinged, psychologically disturbed best in The Cycle Savages, a mediocre biker movie with a threadbare plot. Filmed on location in the Silver Lake and Echo Park neighborhoods of Los Angeles, the movie is a rather downbeat affair. Dern’s portrayal of Keeg, the leader of a biker gang engaged in the white slavery racket, is so viscerally raw and cruel, that one forgets that one is even watching a fine actor at work.

But it takes more than a dastardly villain to make a movie work. It also takes a hero. In Cycle Savages, we really don’t get much. The only person in the neighborhood who seems willing to stand up to Keeg is Romko (Chris Robinson), a pensive, sensitive artist originally from the Eastern Bloc. Unfortunately, Robinson’s portrayal of Romko doesn’t exactly leave one feeling inspired. At least he has a pretty girl at his side. Lea (Melody Patterson) is playing both ends against the middle. She’s working for Keeg, but also falling in love with Romko. If this doesn’t seem to entice you, then I’d suggest that you’re not going to find much in the plot to keep you interested.

What makes this film somewhat worth a look – aside from Dern’s over the top madman portrayal – is the fact that it’s very much a slice of life from a specific place at a specific time. One imagines that the filmmakers had some sense of the sleazy biker counterculture that existed in late 1960s Los Angeles and how a biker gang could really ruin a neighborhood. There is actually a great deal of meanness on display here, including an implied gang rape scene that would be difficult to put on screen today.

But is there a message in the movie? Or is it just sheer exploitation? If it’s the latter, the movie could have benefited from some more memorable characters and better music. One can thoroughly appreciate Dern as an actor, but a movie needs more than a vindictive, misogynistic villain to make it worth the price of admission. Caveat emptor.