Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

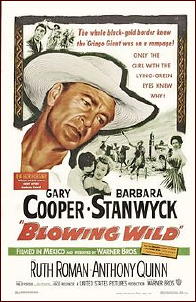

BLOWING WILD. Warner Brothers, 1953. Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwyck, Anthony Quinn, Ruth Roman, Ward Bond, Ian MacDonald. Screenplay by Philip Yordan. Directed by Hugo Fregonese.

The spicy pulp and paperback original spirit lives in this adventure film/soap opera with a few noirish touches.

The setting is somewhere in Central America in what was then contemporary times. Jeffrey Dawson (Gary Cooper) and Dutch (Ward Bond) are wildcat oilmen whose lease is destroyed by bandits leaving them to hitchhike back to civilization looking for work. Along the way they meet a tough smart but vulnerable girl (Ruth Roman) of a type not unusual in adventure fiction — good girl, but not a fanatic about it — and get cheated out of money owed them for delivering nitro to a well through bandit country by a four-flusher (Ian MacDonald).

Dutch is wounded and Jeff needs money, meaning he has to turn to old pal Paco Conway (Anthony Quinn) who the two encountered earlier, but turning to Paco, now a successful oilman, is the last thing Jeff wants to do because Paco is married to Marina (Barbara Stanwyck) who Jeff once loved, and Marina is bad news, twisted, destructive, promiscuous, and sick to death of her husband. Both she and Roman’s character might have crawled out of any Gold Medal paperback of the era full blown.

To say Marina has a thing for Jeff is putting it mildly, Marina is a female jaguar in heat, and just about as dangerous to all involved. There is enough wattage in the scene where she comes to Jeff’s bedroom and he turns a lamp on her in the doorway like a spotlight to power a small town for a week, although it is all underplayed, and fully clothed.

Stanwyck was unsurpassed at portraying female lust with just a smoldering look and a raspy tone of voice. Just watching her, and remembering the heat she and Cooper engendered back in Ball of Fire and Meet John Doe, you fear for Cooper’s characters virtue — however tarnished and shopworn it may be.

Paco, meanwhile, has troubles, a wife who doesn’t love him and who, along with his success, has caused him to lose his nerve; and, those self same bandits who blew up Jeff and Dutch’s well and now threaten all that Paco owns.

No surprises in this film. It is shot handsomely on location and you get a lot of shots of Stanwyck whipping her galloping horse in various states of sexual frustration to the Frankie Laine theme song from Dimitri Tiomkin, plenty of the patented Stanwyck look of passionate fires just barely tamped down enough not to escape, and, of course, also Stanwyck flaring whenever crossed by her husband or Jeff. At times you half to expect her to throw herself off the screen and sexually assault the nearest man.

You know going in there will have to be a shootout with the bandits and that Stanwyck won’t long put up with Paco in the way of her passion for Jeff, that Paco will finally interpret those hot long looks Marina gives Jeff and react violently, and just as certainly the pump jack in the courtyard of their hacienda, that was the first well Paco hit it big with and the noise from which drives Marina mad, is going to play a role in how both their marriage and their lives end.

Having spent part of my youth with an oilman father and grandfather, I can testify to how annoying a pump jack in the yard can be, even if it is pumping your family’s money from the ground. Blowing Wild is a bit closer to oil field reality than most. At least it got a few details right, and God knows I knew enough men like Jeff, Dutch, and Paco in my youth, and no few women like Stanwyck’s Marina or Roman’s character around them if they didn’t quite look like their Hollywood counterparts or have Philip Yordan writing their sharp innuendo laden dialogue.

Even Ian MacDonald’s four flushing cheat is true enough to life. The oil business may be one of the few industries in the world as colorful as its publicity. at least it was then.

Blowing Wild is professionally done, tightly directed, and with an impeccable cast. It is pulp dressed up with a touch of Freud and Kraft-Ebling and a slight noir glaze, but it is well done for all that, diverting, and just about any film with that cast, screenwriter, and director would hold me for at least the running time.

Granted it is almost done in semaphore, the obvious nature of every scene telegraphed well before it appears. It’s a not-quite Western in an adult mode, more than worth watching, just for Cooper, Stanwyck, and Quinn in my case, and if you can get that Frankie Laine theme song out of your head for a day or two after watching it you are a better man than I. (*)

(*) And yes, I could hear Bosley Crowther, the famous film critic who liked to sum up films in plays on their titles, commenting, Blowing Mild, but honestly it is a perfectly good middling Gold Medal original of a film you will almost certainly enjoy in the right mood.