REVIEWED BY WALKER MARTIN:

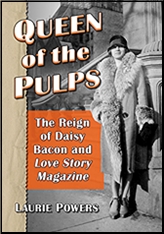

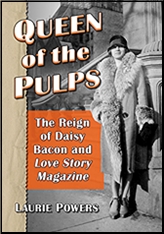

LAURIE POWERS – Queen of the Pulps: The Reign of Daisy Bacon and Love Story Magazine. McFarland, paperback, September 2019.

Have you ever received a book in the mail and immediately stopped what you were reading, stopped whatever you were doing and sat down and read the book? This is what happened when I received Queen of the Pulps. I had seen Laurie Powers work and do research on it for several years and finally here it is! She must of gotten sick and tired of me nagging her about the book and asking for progress reports.

This book breaks new ground and stresses original research on the love and romance magazines. Recently there have been some excellent books about the pulps such as John Campbell and Astounding Science Fiction, Joseph Shaw and Black Mask (forthcoming from Altus Press/Steeger Books this November), and in a few months, Michelle Nolan’s book on the sport pulps. Many collectors have been saying that we live in the Golden Age of Pulp Reprints, well it looks like there is a Golden Age of Pulp Studies also.

It’s exciting to realize that these books are not just run of the mill academic studies. They cover three of the greatest pulp editors: John Campbell, the greatest of the SF editors in the forties, Joseph Shaw, the greatest of the hard boiled detective pulp editors, and Daisy Bacon, the greatest of the love and romance pulp editors. Now all we need are books on Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, the greatest of the adventure pulp editors and Farnsworth Wright, the greatest editor of the fantastic and supernatural pulps.

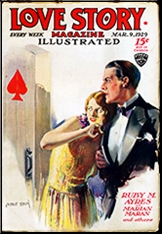

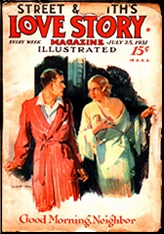

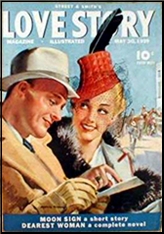

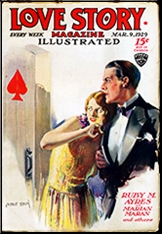

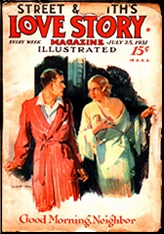

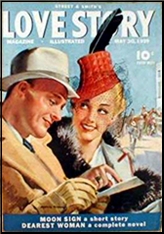

The book is a real beauty and very impressive looking. Laurie spared no expense and gathered over 80 photographs which are reproduced on high quality book paper and thus show up very well. She also has five color photos of Love Story covers. I like the way the photos are spread throughout the book and not just squeezed in a few pages. In the back of the book are around 300 chapter notes and footnotes documenting the facts, also an extensive bibliography and index. It is very obvious that this is a labor of love for Laurie and the excellent final results make all her hard work worth it.

But in addition to the above, there is another reason why I love this book. Starting in 1972 I attended the yearly Pulpcon conventions where just about all the conversations centered around the hero pulps. Titles like The Shadow, Doc Savage, G-8 and His Battle Aces, Operator 5, etc. There also was some interest in science fiction and many of the old timers(all these great old pals now gone), loved Max Brand and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

You might think this must have been a great time but for me, it was not. Though I ended up collecting just about all the hero pulps, I hated them with a passion. I know many of my collector friends will gasp in horror at such sacrilege, but I couldn’t stand the heroes and every attempt to read them defeated me because of the childish plots and dialog. At least with a love pulp you are dealing with a subject that makes the world go round. Love! But I positively disliked the silly Monk and Ham characters in Doc Savage and Bull and Nippy in G-8.

So, in the early days of pulp fandom there was very little interest in other genres like detective, western, adventure, and sport fiction. And certainly there was absolutely no interest in collecting the love and romance pulps. Sure there were a couple lost souls like me, Digges La Touche, and even Steve Lewis. We picked up issues here and there over the years and now I guess I have a couple hundred Love Story issues without even trying.

However, as the years and decades marched on, things began to change and collectors started to collect the other genres, the pulps that adults read and not just the hero pulps which were aimed at the teen-age boy market. I even did an informal survey in the seventies and eighties where I asked many non-collectors if they remembered the pulps. Many of the women remembered the love and general interest pulps and many of the men remembered and read Black Mask, Argosy, Adventure, Western Story, etc. When I directly asked them about the hero titles, the usual response was did I mean the “kid pulps”, or as one of my old time friends said “the magazines with the unreadable crap” (Harry–Damn it you said you would get back to me about the afterlife!).

Now finally we have a book that back in the 1970’s I never thought would be published. It is not about the hero pulps, rehashing old tired comments but about one of the most successful editors, Daisy Bacon. For 20 years, 1928–1947, she edited Love Story which had the highest circulation of all the pulps, estimated to reach 600,000 per issue.

Queen of the Pulps is not only about Daisy Bacon and Love Story, but also about editing in general at Street & Smith. Daisy edited seven other titles in addition to Love Story and though the main thrust of this book is about that magazine, Laurie Powers also discusses Daisy’s time editing Detective Story for most of the decade in the forties. She also covers her time as editor of the final issues of The Shadow and Doc Savage.

It sounds like she enjoyed the change of pace from love to murder. For 25 years Detective Story had published a sort of bland and sedate detective story, just about ignoring the hard boiled style sweeping through the other quality detective titles like Black Mask, Dime Detective, and Detective Fiction Weekly. During this period, 1915–1940, the magazine avoided the tough, hard boiled fiction except for an occasional story from Carroll John Daly, Erle Stanley Gardner, and Cornell Woolrich, etc.

But when Daisy Bacon took over as editor in 1941, Detective Story took on new life and she encouraged many of the writers from Black Mask and Dime Detective to write for Detective Story. Raymond Chandler, Dale Clark, T.T. Flynn, G.T. Fleming-Roberts, Julius Long, D.L. Champion, Norbert Davis, John K. Butler, Day Keene, John D. MacDonald, and others all appeared once or twice.

It’s obvious she wanted to make the stories tougher, and she got Carroll John Daly to write six novelets, Fred Brown to write nine shorts, William Campbell Gault to appear 14 times, and her best author during the forties, Roger Torrey. Torrey had 13 novelets, all starring Irish private eyes, and these stories are worth looking up because they represent his very best work. Torrey unfortunate had a severe drinking problem and drank himself to death around 1945. I read about his death in one of his short story collections and it’s a real sad story.

Daisy Bacon’s reward for all this? She was fired in 1949 during the bloodiest day in pulp history as Street & Smith killed off all its pulp titles (the one exception for some reason being Astounding). Western Story, over 1250 issues—Gone! Detective Story, over a thousand issues–Gone! It seems that the president of Street & Smith hated the pulps and saw the future as slick women’s magazines. These slicks are so dated and worthless that just about no one collects them nowadays. But the Breakers love them because they cut out the slick ads and sell them to housewives and men to frame them in their basement bars or kitchens.

What is this guy’s name? Allen Grammer, who was hired by the family to run Street & Smith, the first such outsider in almost a hundred years of publishing. When he came on board in 1938, he had no interest in the pulps and almost from the very beginning worked to get them out of circulation. Needless to say, he and Daisy did not get along and he got rid of her along with the pulp titles.

On a more personal note, I became involved with the Grammer family. What’s the odds of a non-collector having two pulp cover paintings and moving right next door to a collector with a house full of pulp art? A billion to one? Will it happened to me. In the mid-1990’s an elderly retired music teacher moved next door and had an open house for the neighbors to get acquainted. As my wife and I walked through his house we were stunned to see two original cover paintings from Western Story hanging on the wall of the den.

They both were from 1938 and painted by Walter Haskell Hinton. I immediately cornered my host and discovered that his name was Paul Grammer and he was the nephew of Allen Grammer. It seemed his uncle was the head executive at Street & Smith back decades ago and Paul Grammer’s father also had a high position. Eventually when Allen Grammer died, Paul inherited the pulp cover paintings. Several years later Paul gave in to my pleas and sold me the two paintings. Every time I look at the one I still have, I think of Paul and wish he still lived next door.

Over the years I had several conversations with Paul about his infamous uncle and I sure wish Paul was still alive because I have even more questions now that this Daisy Bacon book is out. Paul once showed me a photograph of Allen Grammer sitting behind his desk at the Street & Smith offices. Behind him was a large pulp painting by N.C. Wyeth. I commented that the painting was now worth a million dollars and Paul said one day his uncle went into the office and the painting was gone. Someone had walked out with it. I wish I had talked Paul Grammer into letting me have the photo because I see that Laurie does not have one of Allen Grammer in the book. I suspect Laurie sympathized with Daisy and also dislikes him. Thus no photo! (Or maybe she could not get the rights to publish a photo.)

So, for several years I watched Laurie got deeper and deeper into the life of Daisy Bacon. More than once Laurie traveled from California to New York and New Jersey. She discovered the old records, photographs, diaries, and various papers that Daisy had kept all her long life. On one trip she even discovered the love nest built by Daisy’s long time lover in the woods of New Jersey. Laurie even came across and now owns, the one painting that Daisy kept by Modest Stein. By the way, love pulp cover paintings are rare. I’ve only found two: one for Love Book and one for All Story Love.

The book is full of fascinating details and stories about Daisy, her half sister, Esther Ford, her mother, and her lover. Laurie has told a suspenseful story worthy of being published in Love Story magazine. Of course the part about the secret lover would have to edited out of the story. It has all the pulp story ingredients: love, attempted suicide, secret lives, success, depression, and failure.

If you read the pulps, buy the pulp reprints, or collect the old magazines, this book is a must buy. Price is $40 but it’s worth the cost. This gets my highest recommendation and can be bought on amazon.com or the McFarland Books website. If you attend Pulpadventurecon in Bordentown, NJ on November 2, 2019 Laurie will have copies for sale.