Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

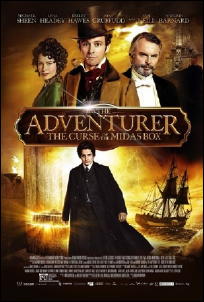

THE ADVENTURER: THE CURSE OF THE MIDAS CUP. 2013. Anuerin Barnard, Michael Sheen, Sam Neill, Ioan Gruffudd, Lena Hedley, Catherine Hawes, Mella Carron, Xavier Atkins. Screenplay by Christian Taylor and Matthew Huffman, based on the young adult novel Mariah Mundi and the Midas Box, by G. P. Taylor. Directed by Jonathan Newman.

This is a mildly entertaining steampunk juvenile tale based on a series by G. P. Taylor, about a young lad named Mariah Mundi (Anuerin Barnard) who is at that awkward age between man and teen. The plot takes a note from Clive Cussler and James Rollins rather than Harry Potter or Percy Jackson, with the McGuffin a mysterious gold box that has the power to turn anything into gold, and Mariah a reluctant young hero forced into improvising a bit of Richard Hannaying (or should that be David Balfouring?) to find it and save his little brother who has been kidnaped by a ruthless master criminal.

Evil Otto Luger (Sam Neill) knows the box can give life or destroy it and he wants the power along with the evil mastermind behind him, the mysterious Gomberg.

All of which leads to London where Mariah is attending a lecture by his father along with his mother and his brother Felix (Xavier Atkins). In short order Captain Will Charity (Michael Sheen) shows up seriously wounded by Luger to warn the Mundi’s of Luger’s quest, seems he and Mariah’s parents (Ioan Gruffudd and Catherine Hawes) are secret agents for the Bureau of Antiquities, and have dealt with ruthless Otto before.

Charity takes off (he’s always doing that then popping up at convenient times), the Mundis disappear, and Mariah and Felix are fleeing Luger’s men in their robes and night clothes before the night’s over, but not before their mother gives each of them half of an amulet and a mysterious bit of doggerel to remember.

Charity pops in to rescue Mariah in time to save him from Luger’s men but Felix is captured, Luger now has half of the amulet, and Mariah finds himself on the way to a remote North Sea island where Luger owns the fabulous Prince Regent resort built right into the mountainous island. Mariah, disguised as a porter, is to seek Felix, and of course Charity takes a hike again. His parents he is told are most likely dead at Luger’s hand, which causes much less angst than you might expect.

Mariah soon discovers that children on the island have been disappearing and no one ventures out after dark because of a monster. Nor is his job easy what with dodging Luger’s men who know his face, Monica (Lena Hedley) the evil female manager of the hotel, Luger himself, and a flamboyant Russian escape artist who shows up adding to the mystery.

With Sacha (Mella Caron), a parlor maid who befriends Mariah, he begins to delve into the mystery, and soon learns Luger is looking for the Midas box beneath the hotel in the mountain. The healing waters the hotel is famous for taking their powers from the box.

Complications pile on: Mariah makes some fair deductions and some narrow escapes with Sacha, a set of magic gypsy cards, and a suit of Midas solid gold armor fit into the plot, two other mysterious men show up also working undercover, and just as Mariah seems about to discover the islands secret Charity appears (two guesses as who) and everything falls apart when he is discovered.

Mariah finds Felix and solves the mystery of the monster (you should be far ahead of him on most of this), but now Sacha is in danger too, Luger has both pieces of the amulet and the gold box, Felix is trapped in a tomb filling with water. Luger and the manager plan to gas them all and the other children forced to dig for the box in tight quarters, and even though the Bureau of Antiquities shows up they are no match for the mysterious box and the power that once destroyed Midas enemies.

You know Mariah will defeat Luger seeing to it that he meets an appropriately grisly end with the aid of that bit of doggerel his mother whispered to him, and Sacha’s drunken father will save her, dying with the evil manageress Monica. All is well, Mariah, Felix, and Sacha receive medals, Mariah asks Sacha to live with them, and they are told the Bureau may call on them again.

For now, Charity informs them, he is hunting Mariah’s living but missing parents and Gomberg, and Mariah has done “very well.â€

Roll the credits — but wait, there is still one revelation left, one so mind-numbingly stupid — I say stupid, but so stupid as to almost be brilliant — as to leave you stunned, but handled quite well, and certainly enough to get you to buy the next book or rent the next movie or at least take a peek in the bookstore.

It’s all playful and fairly inventive, a bit plot heavy and deliberate for today’s youthful audiences, but it doesn’t insult your intelligence, not until the last scene anyway. Fan’s of the books must have been pleased. It’s another film you will want to Netflix or Redbox rather than buy, but you likely will want to see it.

Barnard as Mariah is quite good and he fits the books illustrations well; with the right roles he might even develop as a popular actor. Neill has a fine time as Luger in one of his last roles, and Michael Sheen has fun as the extravagant Will Charity though none have more than one dimension or much chance to do more than sketch in their characters. The cast is uniformly good as are the special effects and sets, especially the hotel’s generators. You may wonder why they wasted Ioan Gruffudd (Horatio Hornblower) in such a minor role, but they really didn’t — but that’s for the sequel.

I may at least check out the books, and the film is entertaining. Though the start was a bit slow I liked it quite a bit, and wouldn’t mind seeing the sequel with the same cast and credits. It’s no match for the Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, or the Series of Unfortunate Events films, but for what it is it is handled well.

It’s actually better than this review, but I don’t want to mislead you. It’s an old fashioned adventure story owing more to Stevenson and Buchan than Rowling or Anthony Horowitz’s Alex Rider, and depending on your taste for that type tale, you will either love it or be entirely indifferent to it. It reminded me of the kind of thing Robert Lewis Taylor (The Travels of Jamie McPheeter and The Treasure of Matacumbe) used to write though not as brilliant or complex, or a juvenile version of some of Macdonald Hastings odder adventure stories. The chief difference being that there is no Alan Breck or Long John Silver character with dubious motives to spice things up. If, like me, you like that future-past genre of steampunk adventure and classic adventure tales, this is right up your alley.

If not, you may find it formulaic, and old-fashioned. It all depends on your fancy for this genre of adventure films. There is something missing here I can’t quite lay my hands on, but it may be as simple as the film is done by rote, and there is no real passion for the story as in the Harry Potter films.

It’s not enough to make a good movie of something like this, you have to love the material and the magic of bringing it to the screen. Without that it is basically a minor A or superior B adventure film and nothing more.

Classics are made when that extra element is present.