REVIEWED BY JON L. BREEN:

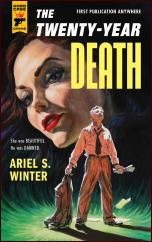

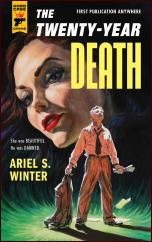

ARIEL S. WINTER – The Twenty-Year Death. Hard Case Crime, hardcover, August 2012; trade paperback, August 2013.

Ariel S. Winter’s The Twenty-Year Death sets a challenge both ambitious and unique: three crime novels, each in the style of a different writer, that could individually stand alone but as a group tell a connected story.

“Malniveau Prison,” set in France in 1931, is a classical detective story with a bizarre plot in the style of Georges Simenon. “Falling Star,” set in 1941 Hollywood, is a hardboiled detective novel inspired by Raymond Chandler. “Police at the Funeral,” set in 1951 Maryland, is fiction noir in the Jim Thompson vein. (That last is one of the great mystery-novel titles, previously used by quite a different writer, Margery Allingham.)

The common character in the trilogy is novelist and screenwriter Shem Rosenkrantz, whose drinking problem and institutionalized wife make clear he was inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald, who for all his faults surely was not as unsympathetic, weak, and pathetic as Shem. Just as well we don’t have to live through three whole books with him. He’s just a minor presence in the first two but no more likable when you get to know him better in the third one.

I believe Winter has done a superb job on all three stories, and they’re worthy of the praise they have received. But what I want to discuss here are some errors and odd choices.

Anachronisms are the bane of historical writers, and as I’ve pointed out before they are both harder to avoid and more likely to be noticed when the history is relatively recent. I don’t believe the term “senior citizens†or a French equivalent was current in 1931, nor was the meaningless expression, “It is what it is.†Nor was Ms used to designate women in 1951, except maybe in regional dialect which is not how it’s used here.

In the Chandler pastiche, British expressions not likely to be used by an American turn up: “the chemist’s†for druggist’s, “in the cinema.†I don’t think Winter, who lives in Baltimore, is British. Is it a nod to the fact that Chandler was educated in Britain? Unlikely, and the typically British phrase “on about†occurs later in the Thompson pastiche. (While it’s true the co-publisher with Hard Case Crime, Titan Books, is headquartered in London, I would assume Charles Ardai was at the editorial reins.)

In “Falling Star,” a horse race is started with a pistol shot. It’s never been done that way to my knowledge, and the odd terminology describing the race makes clear the track is not the author’s milieu.

Moving from errors to odd choices, “Falling Star” takes place in a fantasy Hollywood. Where Chandler famously renamed Santa Monica as Bay City in his Philip Marlowe novels, Winter carries it to a greater extreme, changing place name and street names in a manner disorienting to the Southern California reader. Sunset Boulevard becomes Sommerset, Wilshire becomes Woodsheer.

Even Los Angeles is not called by its right name, becoming San Angelo. As for the racetracks, Santa Anita in Arcadia becomes Santa Theresa in Arcucia, but Hollywood Park keeps its right name, though it is not and never was actually in Hollywood.

Finally, in “Police at the Funeral,” one character reacts to unwelcome news with the following bit of censored dialogue: “S—t! S—t, s—t, s—t.†Now surely, the style book of Hard Case Crime allows for the use of the actual spelled-out obscenity. Would it have been presented this way in Thompson’s day, and is that the reason?

Anyway, quibbles aside, I highly recommend this three-part book. I’m just curious how these particular errors and decisions came to be. Anybody want to speculate?