WICKED GOOD

A Review by Curt J. Evans.

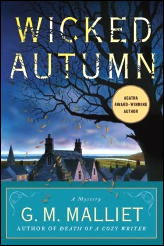

G. M. MALLIET – Wicked Autumn. St. Martin’s/Minotaur Books, hardcover, September 2011.

“Exton Forcett had remained immune from the corrupting influence of feminism. Even the Women’s Institute under the able guidance of Mrs. Laverock had confined itself to domestic matters and remained aloof from local politics. It knitted comforts, it baked meat pies for farmworkers, it made jams of curious and hitherto unknown consistency. None of its members had ever aspired to a seat on the parish council.”

— Miles Burton,

Murder M. D. (1943)

Who doesn’t love a good English village murder (or a “cozy” as these tales often are termed today)? G. M. Malliet, who in 2008 won the Agatha for best first novel for her Death of a Cozy Writer, has triumphantly updated this classic subgenre of English mystery with her fourth novel (the start of a new series), Wicked Autumn. Malliet’s satirical wit is magnificent and her cluing masterly.

Though in writing Wicked Autumn, Malliet no doubt was inspired by Agatha Christie’s grandmother of village mysteries, The Murder at the Vicarage (1930) — I was also much reminded of, from closer to the present day, Ngaio Marsh’s Grave Mistake (1978) and Robert Barnard’s A Little Local Murder (1976) and The Disposal of the Living (1985) — I have quoted above from a lesser known though first-rate English village mystery by Miles Burton (a pseudonym of Cecil John Charles Street), because I wanted to highlight one of the most delightful aspects of Malliet’s novel, her portrayal of the Women’s Institute of her village, Nether Monkslip (the book is dedicated to the National Federation of Women’s Institutes).

The machinations within this group — whose overbearing president, Wanda Batton-Smyth, is murdered in the course of the tale—make highly amusing reading. One of the great pleasures, surely, in the English village mystery is the frequently wicked satire (somewhat belying the reputation of these tales as “cozies” that one finds in it. The Miles Burton passage above, for example, is delivered very much with its author’s tongue in his cheek.

Christie’s brilliant satire in The Murder in the Vicarage — a novel one contemporary reviewer compared to Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford (1851) — is much underappreciated today, but clearly Malliet has learned much from the Great Lady. Malliet’s wickedly barbed writing is an abiding delight throughout Wicked Autumn:

“Wrapped in a fluffy white mohair dress of her own design…her hair clipped short around protuberant ears, she resembled a Chihuahua puppy abandoned in a snowdrift.”

“[The figurine] was made of plaster of Paris and amateurishly painted, the shepherdess’s hectic expression suggesting a facelift operation gone wrong, the receipt of a telegram containing bad news, or the irretrievable loss of her flock.”

“The rest of the room was of a Laura Ashleyish theme of prints and patterns of coordinating colors and contrasting patterns, a style so irredeemably British as to be impossible to eradicate from the Jungian collective design unconscious.”

“A typical man of his generation, Lily’s uncle had taken one look at her knobby-kneed, wiry-haired self, aged twelve, and privately predicted she would never marry unless a female-targeting plague killed off every other woman on the planet.”

The women of the village are similarly memorable, especially Wanda Batton-Smythe, a classic murderee. Wanda is so deliciously obnoxious and objectionable we ironically miss her when she’s gone. She’s a brilliant updating of the village battle-axe matron. Other classic types given updates and new life by Malliet are:

â— Awena Owen, the “New Age” mystic (yes, they had these in the Golden Age mystery too, under different names)

â— Suzanna Winship, the village vamp

â— Mrs. Hooser, the something less than smoothly competent housekeeper

â— Agnes Pitchford, the nosy and keen-minded octogenarian retired schoolmistress (I surely won’t be the only person reminded of Miss Marple and Miss Silver)

â— Major Batton-Smythe, Wanda’s husband (almost straight out of the pages of a Christie)

â— Frank Cuthbert, futile local author (self-published)

Though it is a cliché to say it, a book as delightfully written as Wicked Autumn would be an enjoyable read even without its murder and solution; yet I am pleased to report that Malliet handles this aspect of her tale quite deftly as well. The clues, which are of the textual sort favored by Christie, are close to the level of the great Golden Age Crime Queen herself.

There also ultimately is some poignancy in Malliet’s handling of the Batton-Smyth family (Malliet’s passage on the cruel difference for many couples between the glittering fantasy of retirement and its drab reality is acute) — proof, if it be needed, that the cozy can offer emotional depth as well as surface charm.

Indeed, the solution to the murder in Wicked Autumn is rather un-cozy when one thinks about it. Wicked Autumn definitely illustrates W. H. Auden’s view that the murderer in the English village mystery must be cast out in order to restore the village to its state of grace. In this respect, the novel is more aesthetically pure than some of its Golden Age forebears, where murder occasionally is allowed to pass unpunished.

The detective in the tale is an amateur rather improbably brought in, in classic fashion, to help the police with the investigation: Max Tudor, the local Anglican minister. Max, it seems, used to be MI5. His back story is threaded through the tale. Undoubtedly many readers will find this material of greater interest than I did. (I am of the old school and do not expect my detectives to have interesting back stories.)

I did enjoy Malliet’s thoughts on the present-day status of the Anglican church, however: “Especially in an age when it was felt the church was circling the drains, some people clung to whatever looked certain and solid, making them less able to handle ambiguity and apparent contradiction.”

Naturally, Max is handsome, charming, straight and a bachelor; and Malliet cannily opens several romantic possibilities for him in his first novel. No doubt many Malliet fans (of whom there should be increasing numbers after this novel) will enjoy following how Max’s love life develops. For my part, as long as Malliet keeps writing mysteries this amusing, insightful and clever, I will abide even fairly heavy doses of love interest!

Final Note: I should add that in Wicked Autumn Minotaur Books has produced an extraordinarily attractive book. There is a stunning endpaper map, an apt falling leaf motif running though the pages, and attractive and clear type. In an age where publishing quality often seems increasingly slipshod, Minotaur Books is to be praised along with the author.