REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

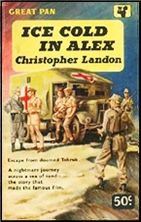

CHRISTOPHER LANDON – Ice Cold in Alex. Heinemann, UK, hardcover, 1957. Sloane, US, hardcover, 1957. Also published as Hot Sands of Hell (Zenith ZB-43, US, paperback, 1960).

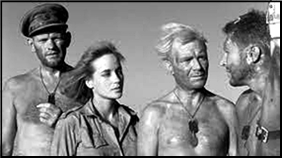

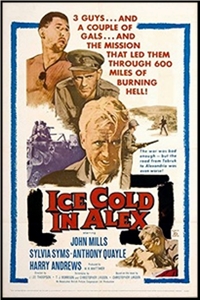

ICE COLD IN ALEX. ABPC, UK, 1958; released in the US as Desert Attack. John Mills, Sylvia Sims, Anthony Quayle, Harry Andrews, Diane Clare, Richard Leach, Liam Redmond, Walter Gotell. Screenplay: T. J. Morrison, based on the novel by Christopher Landon. Directed by J. Lee Thompson.

They served it ice cold in Alex …

“It†is beer, they serve it ice cold in Alexandria, Egypt at the canteen, and for Captain George Anson who is stationed in Tobruk on the eve of its fall to the advancing forces of General Erwin Rommel, beer has become a beacon of hope amid the routine and routine fear of the pounding being taken as Rommel advances and there is less and less chance of survival…

He knew that the fear had come to stay now — not coming and then draining away, as it had for the last two days.

Anson has been drinking more heavily with the fear and now the fear is constant as is the dream of that ice cold drink in Alex. That’s why it seems like a dream when his commander sends him, and Sgt-Major Tom Pugh on a special assignment to escort two nurses across the desert avoiding the Germans to the relative safety of Alexandria.

He can almost taste the beer. “Four Rheingolds come before any bloody war.â€

The two nurses are Sister Diana and Sister Denise, the latter who has nearly lost her nerve under the German bombardment. Anson has missed the convoy, but it they leave now they can rendezvous with another for escort. At least that is the plan.

Like many classics the set-up is a simple one. It’s the complications that follow that make the tale. Complications about the German patrol that lets them go if they will take on the South African civilian Zimmerman with them, like the impossible terrain they are forced to take to avoid more Germans, like mine fields, breakdowns, missed rendezvous, unexpected romance, salt marshes, death, thirst, fear, pain, and just maybe a German spy in their midst and perhaps that he might be their only hope to survive…

Were they very clever … or complete stupid fools? His mind dodged back to every incident … how they reacted … how his own varying moods of contempt and wariness had pulled him this way and that like a straw in the wind.

Christopher Landon is better known in the UK than here, and mostly for this book, though he wrote several other well-received thrillers. Perhaps it was just his fate to come along during the Golden Age of the British thriller at the same time as Hammond Innes, Victor Canning, Alistair MacLean, Gavin Lyall, Desmond Bagley, and Elleston Trevor (whom Landon most closely resembles). Somehow Landon slipped a little between the cracks, at least with American audiences.

It could be some of his books are a bit bleaker than the other writers on that list , that he wanders into Graham Greene country of moral ambiguity and redemption rather than high adventure, or maybe he was just too grounded to compete with the higher flying competition.

Whatever the reason this book was a masterpiece, and it was snapped up for a film.

Some films are better than the book.

This one took a fine book and turned it into a legendary war film, one of the best of its era, one of the best of any era.

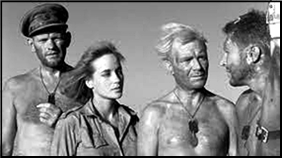

John Mills, the everyman (at least every Englishman) of his acting generation, was Anson. Sylvia Sims was Diana Norton, Harry Andrews (who else) Mechanist Sgt-Major Pugh, and Anthony Quayle, the mysterious man who joins them on their adventure across the Sahara.

J. Lee Thompson of Cape Fear and The Guns of Navarone directed with the same set of skills demonstrated in those other films.

The plot, most of the incidents from the book are the same are but boiled down to a little over two hours, bleakly photographed in black and white, nerve-wracking foot by foot of the journey, their fear, thirst, and distrust writ tautly across the screen, and the nerves ratcheted up right down to the final minutes and the satisfying humanity reaffirming anti climax.

Like Flight of the Phoenix, another adventure film about unlikely survival in the desert this one holds you right down to the end.

Ice Cold In Alex is an anti-war film, it is about humanity among a small group of diverse people in danger. Films like Lost Patrol, Sahara, and Bridge on the River Kwai come to mind. This one stands beside them.

Mills, Quayle, and Andrews steal the show, and Andrews very nearly steals it from the other two. Acting styles may be a bit different than today, some might find there are too many speeches designed to explain things, the considerable acting skills a bit more on the nose than modern audiences are used to.

That really doesn’t matter much. This is a superb film, a classic, one of the best war films from an era when some of the finest war films ever made were being turned out. It features three of the finest actors the British film industry had to offer, and it still has something to say about men in war and where survival outweighs politics.