Reviewed by TONY BAER:

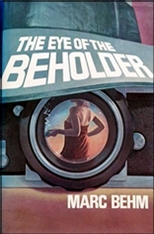

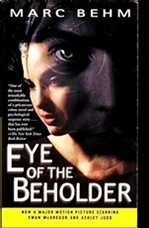

MARC BEHM – Eye of the Beholder. Dial Press, hardcover, 1980. Ballantine, softcover, 1981, 1999. Film #1: Produced in France in 1983 as Mortelle Randonnée, and released in the US as Deadly Circuit. Film #2: Released in 1999, with Ewan McGregor & Ashley Judd.

An old, washed up private eye. At an agency. Divorced. Drinks, smokes. Had a daughter: Maggie. Hasn’t seen her in years. All he’s got left is a 1st grade class photo sent from his ex-wife, on the back, saying I bet you don’t even know which one is her, asshole. And he didn’t. He’d think about her though. In the photo, there were a few candidates that could’ve been her. And he’d pick one and create a whole life, graduation, marriage, kids….

The boss assigns him a case. Rich elderly couple. Their son, Philip, has taken up with some skank, and she’s probably just after his dough. Can you look into her, her background, get some dirt, and watch them, there’s something about her we don’t much trust.

So the Eye follows them, next day, they get married, she and Philip, elope, and honeymoon in a little cottage upstate. The Eye’s watching. Always watching. She’s beautiful. Absolutely stunning. And about the age of his daughter. Hell, maybe it is his daughter. And he watches. Watches as Philip gets ready for bed, the wedding night. I’ll take a quick shower, he says. And he does. And she makes a couple of cognacs, and empties a vial of poison into Philip’s, and before you know it, he’s dead. She buries him in the yard.

And the Eye? He just keeps watching. Enthralled.

The Eye calls his boss, says the happy couple split for Montreal, but don’t worry, tell Philip’s parents the Eye is on their trail.

So Philip’s parents bankroll the Eye’s voyeurism, as he travels from town to town, trailing this beautiful woman who keeps marrying rich young men and murdering them.

And that, my friends, is that. He trails her and watches her and her sordid life, fantasizing that she’s his child, looking out for her, helping her where he can, without her ever knowing, even until the end. Which comes for all of us. Some sooner than others.

It was fine. But I don’t understand the whole hullabaloo, as the book got lots of hype for being something amazing and unique in pi fiction.

Me? I don’t see it. PI’s obsessed with femme fatales? Nothing new under the sun. Thinking the femme fatale’s your daughter? Gross and perverted.

So from me? A meh. It was fine. But it’s not as good as many PI novels, and I don’t see what’s supposed to be so special about it. Behm says he’s not even into the PI genre, doesn’t think much of it. And it shows.