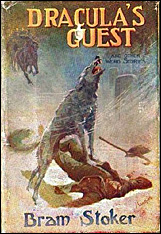

BRAM STOKER – Dracula’s Guest. Published posthumously in the collection Dracula’s Guest and Other Weird Stories (George Routledge & Sons, UK, hardcover, 1914). Reprinted many times including: Weird Tales, December 1927; The Ghouls, edited by Peter Haining (W. H. Allen, UK, hardcover, 1971; Pocket, US, paperback, April 1971); Dracula’s Guest and Other Stories, edited by Victor Ghidalia (Xerox, US, paperback, 1972); Werewolf!, edited by Bill Pronzini (Arbor House, US, hardcover, 1979); The Vampire Archives: The Most Complete Volume of Vampire Tales Ever Published, edited by Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard / Vintage Books, softcover, 2009); The Big Book of Rogues and Villains, edited by Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, softcover, October 24 2017). Film: Among others “inspired” by the story, Universal’s film Dracula’s Daughter (1936) was supposedly based on the tale, but nothing of the plot was used.

It is generally stated and accepted that this story, somewhat complete in itself, was the the first chapter of the original manuscript of Dracula, but deleted for reasons of length. It is told by an unknown narrator, but presumably it was Jonathan Harker who very foolishly ignores the advice of his innkeeper and the coachman of his carriage to get out to investigate on foot a village said to be unholy and abandoned for some 300 years.

On Walpurgis Night, no less. Needless to say, he soon realizes that he has made a dangerous mistake. Some thoughts. First of all, how modern Stoker’s writing is. This is story that could easily pass as having been written last week, if not yesterday. Secondly, it is wonder how well this story anticipates all those Hammer horror films that came along so many years later.

BONUS:

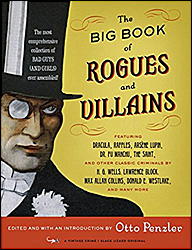

Here are the stories included in the Rogues and Villains anthology:

THE VICTORIANS

At the Edge of the Crater by L. T. Meade & Robert Eustace

The Episode of the Mexican Seer by Grant Allen

The Body Snatcher by Robert Louis Stevenson

Dracula’s Guest by Bram Stoker

The Narrative of Mr. James Rigby by Arthur Morrison

The Ides of March by E. W. Hornung

19TH CENTURY AMERICANS

The Story of a Young Robber by Washington Irving

Moon-Face by Jack London

The Shadow of Quong Lung by C. W. Doyle

THE EDWARDIANS

The Fire of London by Arnold Bennett

Madame Sara by L. T. Meade & Robert Eustace

The Affair of the Man Who Called Himself Hamilton Cleek by Thomas W. Hanshew

The Mysterious Railway Passenger by Maurice Leblan

An Unposted Letter by Newton MacTavish

The Adventure of “The Brain†by Bertram Atkey

The Kailyard Novel by Clifford Ashdown

The Parole of Gevil-Hay by K. & Hesketh Prichard

The Hammerspond Park Burglary by H. G. Wells

The Zayat Kiss by Sax Rohmer

EARLY 20TH CENTURY AMERICANS

The Infallible Godahl by Frederick Irving Anderson

The Caballero’s Way by O. Henry

Conscience in Art by O. Henry

The Unpublishable Memoirs by A. S. W. Rosenbach

The Universal Covered Carpet Tack Company by George Randolph Chester

Boston Blackie’s Code by Jack Boyle

The Gray Seal by Frank L. Packard

The Dignity of Honest Labor by Percival Pollard

The Eyes of the Countess Gerda by May Edginton

The Willow Walk by Sinclair Lewis

A Retrieved Reformation by O. Henry

BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS

The Burglar by John Russell

Portrait of a Murderer by Q. Patrick

Karmesin and the Big Flea by Gerald Kersh

The Very Raffles-Like Episode of Castor and Pollux, Diamonds De Luxe by Harry Stephen Keeler

The Most Dangerous Game by Richard Connell

Four Square Jane by Edgar Wallace

A Fortune in Tin by Edgar Wallace

The Genuine Old Master by David Durham

The Colonel Gives a Party by Everett Rhodes Castle

Footsteps of Fear by Vincent Starrett

The Signed Masterpieces by Frederick Irving Anderson

The Hands of Mr. Ottermole by Thomas Burke

“His Lady†to the Rescue by Bruce Graeme

On Getting an Introduction by Edgar Wallace

The 15 Murderers by Ben Hecht

The Damsel in Distress by Leslie Charteris

THE PULP ERA

After-Dinner Story by William Irish

The Mystery of the Golden Skull by Donald E. Keyhoe

We Are All Dead by Bruno Fischer

Horror Insured by Paul Ernst

A Shock for the Countess by C. S. Montanye

A Shabby Millionaire by Christopher B. Booth

Crimson Shackles by Frederick C. Davis

The Adventure of the Voodoo Moon by Eugene Thomas

The Copper Bowl by George Fielding Eliot

POST-WORLD WAR 2

The Cat-Woman by Erle Stanley Gardner

The Kid Stacks a Deck by Erle Stanley Gardner

The Theft from the Empty Room by Edward D. Hoch

The Shill by Stephen Marlowe

The Dr. Sherrock Commission by Frank McAuliffe

In Round Figures by Erle Stanley Gardner

The Racket Buster by Erle Stanley Gardner

Sweet Music by Robert L. Fish

THE MODERNS

The Ehrengraf Experience by Lawrence Block

Quarry’s Luck by Max Allan Collins

The Partnership by David Morrell

Blackburn Sins by Bradley Denton

The Black Spot by Loren D. Estleman

Car Trouble by Jas A. Petrin

Keller on the Spot by Lawrence Block

Boudin Noir by R. T. Lawton

Like a Thief in the Night by Lawrence Block

Too Many Crooks by Donald E. Westlake