Fri 30 Oct 2015

A Halloween Movie Review: CREATURE WITH THE ATOM BRAIN (1955).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[5] Comments

CREATURE WITH THE ATOM BRAIN. Columbia, 1955. Richard Denning, Angela Stevens, S. John Launer, Michael Granger, Gregory Gay, Linda Bennett, Tristram Coffin. Story & screenplay: Curt Siodmak. Director: Edward L. Cahn.

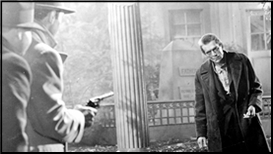

This one starts right out in third gear as soon as the credits have been shown, with an obvious gangster being killed in his office — shown in silhouette his spine is being snapped by what’s apparently a dead man who has climbed through his window — and the story and the action never let up for the full run of the movie, some 70 minutes long.

The next to die at the hands of one of these radio-controlled atomic-powered zombies (for that is what they are) is the District Attorney. What do the two victims, most definitely on opposite sides of the law, have in common? Will there be more? That’s the question that the head of the police laboratory, Dr. Chet Walker (Richard Denning), must answer, with the use of good logic and handy Geiger counters.

One can easily forget that Denning did make a few movies of this type after being Mr. North for a while then becoming Mike Shayne for a while after that, finally ending up in the governor’s office on Hawaii Five-O. His youthful earnestness stood him in good stead in these 50s monster thrillers, I think, for those very reasons.

This one was a lot of fun to watch, crisply filmed with solid plotting and lots of snappy action. A week later now, most of what I saw has started to disappear, noticeably so. Chinese food for the mind, I think.