FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

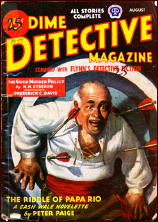

For no reason I can put my finger on, I recently felt an urge to reread some of Dashiell Hammett’s shorter work. Again for no particular reason, my starting point was not a Continental Op story but “The Assistant Murderer,†which was first published in Black Mask for February 1926 and is most easily accessed today in Hammett’s Crime Stories & Other Writings (Library of America, 2001).

In his only published exploit, spectacularly ugly Baltimore PI Alec Rush is retained by a young banker to find out why someone is shadowing a gal he’s sweet on but was forced to fire. Soon Rush discovers that the shadow has been paid by two different women to kill the gal in question.

From there the plot gets more convoluted by the minute. The journal I kept in my salad days tells me that I first read this novelette early in 1965, not long after my 22nd birthday and during my first year in law school. Back then I loved it. Half a century later I still like it but perhaps with a bit less enthusiasm.

What I found most interesting today is not so much the plot or characterizations or style but the legal aspects. Which, like those of another Hammett story I discussed in an earlier column, leave something to be desired.

To explain where Hammett went off the tracks requires me to spoil some of the plot, but I’ll try to minimize the spoliation by translating the situation into a sort of law examination question. A, who died long before the story begins, left an estate of roughly $2,000,000, a princely sum back in the early 20th century and not to be sneezed at even today.

He had two sons, B and C. His will created a trust excluding B, whose lifestyle he disapproved of, and naming C as sole income beneficiary. The will specified that C was free to share the income with B to whatever extent he chose, which he would have been free to do anyway.

Typically for a Hammett character, C had chosen to keep the entire income for himself. B dies, a widower survived by a daughter whom we’ll call D. Under A’s will, on C’s death the corpus of the trust is to be divided among A’s grandchildren. Since C is unmarried and childless, this means that on his death everything will go to D. As chance would have it, D is married to a sort of Iago figure who manipulates her into killing Uncle C.

The husband’s scheme doesn’t require that his wife D be tagged for the murder but whether she is or isn’t leaves him cold. “If they hanged her,†he tells Rush at the climax, “the two million would come to me. If she got a long term in prison, I’d have the handling of the money at least.â€

Wrong, Dash! If D were to be convicted of C’s murder, the old common-law maxim that you can’t profit by your own crime would come into play, and the A trust fund would wind up by intestate succession in the hands of various remote relatives of whose identity Hammett tells us nothing. In the absence of such relatives, the fund would probably end up in the coffers of the state of Maryland by a process known as escheat.

But suppose D were only suspected of the murder. Suppose she were never tried for it, or were tried and acquitted, or were convicted but had her conviction overturned on appeal? Could those remote relatives or the state of Maryland sue to divest her of the inheritance in civil court, where her guilt would have to be proved by a mere preponderance of the evidence, not beyond a reasonable doubt as in a criminal trial?

You may well ask! I used to throw out that kind of question to my class when I was teaching Decedents’ Estates and Trusts, but this column is already sinking under the weight of legalese and I won’t deal with that issue unless someone asks me to.

Another aspect of “The Assistant Murderer†that intrigued me was: How many turns of phrase in this almost 90-year-old story need to be explained to readers today? At one point a lowlife tells Alec Rush that “A certain party comes to me with a knock-down from a party that knows me.â€

The Library of America editors explain that a knock-down is slang for an introduction. But a few pages further on, Rush says: “I can see just enough to get myself tangled up if I don’t watch Harvey.†There is no character named Harvey in the story. Did the Library of America people feel that the meaning of this phrase would be clear to readers?

It certainly wasn’t to me. But googling the two words along with Hammett’s name led me to A Dashiell Hammett Companion (Greenwood Press, 2000) by Robert L. Gale, who calls it “an inexplicable reference.†I concur. And in caps!

Let’s migrate from one end of the crime spectrum to the other. I scrutinized every line of James E. Keirans’ John Dickson Carr Companion before it was published but somehow I missed the absence of one Carr adaptation that Keirans missed too. Among the flood of TV PI shows that followed in the wake of Peter Gunn was Markham (1959-60), a 30-minute series starring suave Ray Milland as lawyer-turned-private-investigator Roy Markham.

Most of the scripts for the 59 episodes of this series were originals but a few were based on published short stories by well-known writers — including Ed Lacy and Henry Slesar — and one was adapted from a Carr radio drama. In “The Phantom Archer†(March 31, 1960) an English nobleman calls on Markham to help fight a ghostly archer who is roaming the halls of a historic manor.

Carr’s radio play of the same name was first heard on the CBS series Suspense (March 9, 1943) and the script was published in EQMM for June 1948 and collected in The Door to Doom and Other Detections (1980). Who directed and scripted this Markham episode remain unknown but the cast included Murray Matheson and Eunice Gayson. There are eleven references to “The Phantom Archer†in the index to Keirans’ book but there should have been a twelfth.