Wed 16 Mar 2011

by Curt J. Evans

Anna Katharine Green’s milestone American detective novel, The Leavenworth Case (1878), was reprinted last year in an attractive new edition as part of the Penguin Classics series, which now puts the tale in the company of such distinguished nineteenth-century works with detection and sensation elements as Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (1853), Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) and Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1868).

“Some critics disparage [Green’s] characters’ occasional florid speeches” in The Leavenworth Case, admits Michael Sims in his Introduction to the new edition of the tale. Nevertheless Sims contends that while “now and then [Green’s] storytelling [in The Leavenworth Case] is as leisurely as you would expect from a nineteenth-century novel,” the author “keeps the dialogue lively and mostly convincing.”

I would have to dispute Sims’ contention. Except in the effective portrayal of the archetypal “nosey spinster” character, Amelia Butterworth (who appears in three later Green mystery novels), lively and convincing dialogue did not flow easily from the pen of Anna Katharine Green. Indeed, during the numerous high stress situations in Leavenworth, the dialogue, which is never memorable, becomes positively purple (and therefore false), as the character prate like bad stage actors in fifth-rate melodramas:

Put simply (as she herself too infrequently put things), Anna Katharine Green was not a scintillating writer. To get to the puzzle plots in her tales, one must wade through shoals of prose that ranges from the merely tedious to the truly tiresome. Even forty years after Leavenworth, as the Twenties roared just around the corner (and with it the Golden Age of detective fiction), Green, in The Mystery of the Hasty Arrow (1917) continued to write unattractively and unpersuasively:

and:

And Green’s characters still have a pronounced tendency to orate, rather than speak naturally, as real-world human beings:

I found Arrow too dully written to bear with over its great length (despite some excellent “multimedia” floor plans that are like something out of one of S. S. Van Dine’s Philo Vance murder cases), yet I wondered about Michael Sims’ implication that the leaden prolixity of Green’s writing simply reflected her literary age. For my part, I certainly had not remembered Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins being unable to sketch appealing, believable characters.

So for purpose of this review I decided to read three fairly short “sensationalist” works by three Victoran authors: Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s “The Mystery at Fernwood”(1862), Wilkie Collins’ “Who Killed Zebedee?” (1881) and Benjamin Leopold Farjeon’s Devlin the Barber (1888).

In each case I found that, while, the works offered nothing in the way of the more complex detection found in the tales of Anna Katharine Green, nevertheless they each contrastingly offered believable characters and emotionally compelling situations and as a result were vastly more enjoyable to read.

“The Mystery at Fernwood” and “Who Killed Zebedee?” are long short stories (about forty and twenty-five pages, respectively; the latter is also known, more prosaically, as Mr. Policeman and the Cook).

In “Fernwood” Mary Braddon effectively mines the Gothic tradition that had been first struck in Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) and that perhaps produced it richest early lode of ore with Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). In many of Braddon’s verbose triple-decker sensation novels, appealing mystery elements are too much submerged in love stories (see, for example, Wyllard’s Weird, 1885), but that is not so with the lean and spare Fernwood.

In this tale, a young woman finds not only mystery but grave menace when she visits Fernwood, the decaying Yorkshire country estate of her fiancee. “No, Isabel, I do not consider that Lady Adela seconded her son’s invitation at all warmly,” fatefully announces the heroine’s aunt in the first line of the story.

Academics might strain hard with this tale to find deep meaning about the position of women in Victorian England, but I do not see it myself. However, “Fernwood” is a rattlingly suspenseful tale (even if you pierce the veil of the mystery quickly, as you probably will) and a fine example of the grand and hallowed Gothic tradition that has extended right up to this day in such mystery genre works as Barbara Vine’s The Minotaur (2005).

Wilkie Collins’ “Who Killed Zebedee?” at first seems, with its title and its setting (a lodging house full of eccentric characters), to have popped straight out of the Golden Age of the detective novel (1920-1939), rather than the Victorian era. A frantic cook bursts into a police station, armed with a doleful tale of murder at the lodging house in which she is employed. The victim is one John Zebedee, who was stabbed to death in his bed.

Suspicion immediately falls on Zebedee’s wife, a somnambulist. People fearing a repetition of another Wilkie Collins tale will be pleased to see other suspects emerge among the company of lodgers, most obviously the dandified Mr. Deluc. Desirous of helping the law is the nosy elderly spinster Miss Mybus, yet another interesting early incarnation of a character type most strongly associated today with Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple.

The attention to police procedure and the thumbnail character sketches in “Zebedee” are quite good, making one wish that the tale had been expanded into a full-length novel. As it stands,”Zebedee” is a disappointment as a tale of detection, with the solution coming essentially fortuitously.

To be blunt, “Zebedee” is more luckstone than Moonstone. Collins is more interested here in exploring character, however, and he does this very well, even providing a surprisingly ambivalent ending in the modern fashion.

The only novel among these three works is Devlin the Barber, a striking admixture of mystery and horror elements authored by the prolific novelist Benjamin Farjeon (father of the beloved children’s book writer Eleanor Farjeon).

Luridly advertised on London billboards with an illustration of a young woman bloodily stabbed by a seeming maniac, the book appeared the same year as the Jack the Ripper serial killings horrified England (what are considered to be the genuine Ripper murders took place in 1888 between the dates of August 31 and November 9; Farjeon’s work appeared in serial and book form later that year). Devlin the Barber seems quite obviously to draw not only on the Ripper killings but the gruesome legend of Sweeney Todd, the demon barber.

Devlin the Barber was called a “disagreeable but certainly ingenious tale” when it first appeared and since then has customarily been deemed the best of Farjeon’s many fictional works (only a few of which were sensationalist). Three years before the appearance of Devlin, Farjeon had written Great Porter Square (1885), the first of several praised mystery novels. The man clearly had a talent for crime writing, even though Devlin surely to an extent has to be seen as an opportunistic effort (if an inspired one).

Despite its clear linkage with Jack the Ripper, Devlin opens with only one slaying, that of a nice, middle class young woman who for some reason was keeping a secret late-night rendezvous. After she is found fatally stabbed, it is learned that her twin sister (twins were quite popular in crime books before the Golden Age) has disappeared.

The young ladies’ wealthy uncle, lately returned from Australia, for no particularly compelling reason offers the narrator of the tale, an out-of-work, middle-class friend of the family, a grand sum to solve the case (naturally he has no faith in the police).

The narrator soon finds that the murdered woman had a gentleman friend, but he seems like a winning young man (he is even wealthy and has a responsible guardian). The most striking event occurs, however, when the narrator is called upon for help by his former nursemaid, Mrs. Lemon (could this have been the mother of Hercule Poirot’s future secretary — I certainly hope so). It seems Mrs. Lemon has a very odd lodger indeed, a barber named Mr. Devlin….

Mrs. Lemon’s tale of her frightening lodger, which takes up over a fourth of the book (fifty of the Arno Press edition’s 190 pages), is a tour de force of horror narration. It is almost a disappointment when we come back to the mystery investigation. But now we have a new investigator of the heinous murder: Mr. Devlin himself! If you thought this novel was going to take the same turn of events as Marie Belloc Lowndes’ famous Ripper tale, The Lodger (1913), think again.

More could be said about this fascinating novel, but I will leave the reader to seek out the book for him/herself. I will simply add that, in contrast with The Leavenworth Case, the narrative throughout Devlin the Barber (published ten years later) is smooth and idiomatic, a reader’s delight. Even the cry of the murdered woman’s beloved is not nearly so melodramatic as the contrived speeches you find in Leavenworth:

The long narrative of Mrs. Lemon is especially fine. Like the better-known Braddon and Collins, Farjeon was an effective spinner of tales.

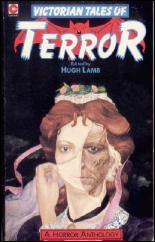

Anyone wanting a good murder story from the Victorian era is advised to seek out these works by Mary Braddon, Wilkie Collins and Benjamin Farjeon. They may be old, but they still speak to us today. During the last decade “The Mystery at Fernwood” and “Who Killed Zebedee?” have been reprinted in attractive editions by Hesperus Press, an admirable publisher of shorter literary classics. (The former has also been collected several times, including in Victorian Tales of Terror, edited by Hugh Lamb, as shown.)

Devlin the Barber, however, stands in need today of a modern scholarly edition (the 1978 Arno Press reprint edition itself is now a rare and valuable collector’s item). Perhaps Penguin Classics will heed the call.