Mon 27 Apr 2009

Archived Review/Author Profile: WILLIAM MURRAY – I’m Getting Killed Right Here.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Reviews1 Comment

WILLIAM MURRAY – I’m Getting Killed Right Here.

Bantam; reprint paperback, July 1992. Hardcover edition: Doubleday, November 1991.

You may already know this, but William Murray, author of the Shifty Lou Anderson books, of which this is one, died in 2005 at the age of 78. He wrote nine in the series,and even though this is the first one I’ve read, it will not be the last.

Shifty, who tells the stories himself, is what you might call a “close up magician” by vocation and a steady habitue or patron of the racetracks by avocation. Here, first of all, is a list of the nine Shifty Lou Anderson novels:

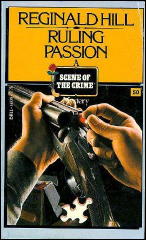

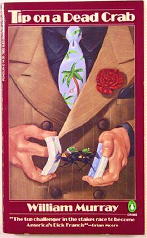

Tip on a Dead Crab. Viking Press, hc, April 1984.

Penguin, pb, 1985.

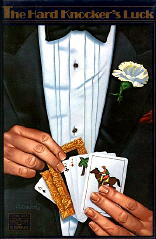

The Hard Knocker’s Luck. Viking Press, hc, October 1985.

Penguin, pb, July 1986.

When the Fat Man Sings. Bantam, hc, September 1987.

Bantam, pb, June 1988.

Bantam, pb, June 1990.

The King of the Nightcap. Bantam, hc, July 1989.

Bantam, pb, July 1990.

The Getaway Blues. Bantam, hc, August 1990.

Bantam, pb, May 1991.

I’m Getting Killed Right Here. Doubleday, hc, November 1991.

Bantam, pb, July 1992.

We’re Off to See the Killer. Doubleday, hc, September 1993.

No paperback edition.

Now You See Her, Now You Don’t. Henry Holt & Co., hc, October 1994.

No paperback edition.

A Fine Italian Hand. M. Evans & Co., hc, May 1996.

No paperback edition.

This list does not constitute all of his mystery fiction. Here’s the rest, all but the last appearing before the first Shifty Lou book:

Passport to Terror. Avon T-423, pbo, 1960, as by Max Daniels.

“Love me tonight,” she whispered. “Tomorrow you’ll spit on my grave.”

The Sweet Ride. New American Library, 1967. Signet, pb, 1967.

A novel of the restless generation, the young people who are rebels against authority and accepted conventions – a new breed of youth, the rootless, purposeless ones who want nothing more than a “sweet ride” on drinks, drugs, and sex – but mostly on the ever pounding beckoning surf. [Stated as being only marginally crime fiction in Crime Fiction IV.]

The Killing Touch. Dutton, hc, 1974. [No paperback edition.]

This taut, fast paced novel is not just about an isolated killing, but, more important, about some of the many ways man and women kill each other – through illusion, deceit, even simple neglect.

The Mouth of the Wolf. Little Brown, hc,1977. [No paperback edition.]

A millionaire’s grandson brutally snatched from the streets of Rome.

The Myrmidon Project. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, hc, 1981, with Chuck Scarborough. Ace, pb, 1982.

A highly rated TV newsman about to retire is hit by a series of personal tragedies, perhaps at the instigation of the chairman of his network.

Dead Heat. Eclipse Press, hc, Sept 2005. [Published posthumously.]

A female jockey searches out a crusty old trainer to help take her to the top.

This does not include any non-crime-related fiction, if any, nor have I attempted to list his non-fiction. Among the latter, however, and not surprisingly, is one entitled The Right Horse: Winning More, Losing Less, and Having a Great Time at the Racetrack. (Never having been to a racetrack, I assume that I am correct in assuming that this is non-fiction.)

From an online tribute to Murray by Robert Cancel comes the following information:

Many of the Shifty Lou Anderson characters and venues were based around tracks in southern California, particularly Del Mar, often framed “in imagery reminiscent of Damon Runyon.” One mystery novel managed to combine two of Murray’s passions, When Fat Man Sings, which is “set in the worlds of horse-racing and opera, with a protagonist reminiscent of Pavarotti, but with a gambling problem.”

What’s at the center of I’m Getting Killed Right Here – which is also the punch line of a joke told on page 166, sort of – is that for the first time, Shifty is an insider at the racetrack.

He owns a horse, one that is possibly going to be a very good race horse, but as Charlie Pickard, Mad Margaret’s trainer, reminds him of very early on, don’t count on anything. There are ten thousand ways to lose a race.

Unable to feed and maintain a horse on his own on a magician’s less-than-reliable salary, Shifty needs to take on a partner, and in this case it’s a guy who turns out to have made millions in the construction business, and who also (not so incidentally) has a wife who is a looker (the general consensus) and who is also much younger than he is.

It may not take more than a nudge from me for you to know where this is going right now. It certainly didn’t take very long for me. One brief motel scene later – well, OK, I guess that was more than a nudge, wasn’t it? – Shifty’s new partner knows what has transpires, and he, Shifty, not to mention Linda, is in a good deal of trouble.

Here’s a quickie description of the sort of business problems Shifty’s new partner is having, quoting from page 55:

“Nothing major,” Arnie added, “just the healthy American pursuit of a buck. I love free enterprise, don’t you? I wonder when somebody’s going to try it.”

Shifty is in over his head, and he damned well knows it. And yet, while this particular escapade on Shifty’s part starts out in rip-roaring old-fashioned Gold Medal fashion, Murray allowed this mammoth sense of impending disaster to be brushed off far too easily, and a the story heads off instead in a modified, somewhat more dignified, and — unfortunately — far more predictable fashion.

Which is not to say that the Gold Medal type of story was not predictable. You know: the one in which the guy gets caught making love to another’s guy younger and good-looking wife, when the second guy belongs to the mob and has connections.

Mr. Cameron, that’s the partner, is a villain through and through, of that there’s no doubt, so don’t get me wrong, but there is another villain behind him and while attempts are made along these lines to keep his role secret, there simply are no doubts at any time about who he is. (This is one of those books in which as soon as the Bad Guy makes his appearance, you know, somehow deep inside, that he is the Bad Guy.)

A detective story this is not, in other words, which to some minds (mine) may leave the ending in something of an anti-climactic nature, but on occasion I am of a forgiving nature, and this is one of them. Shifty’s buddies (Damon Runyonesque, the lot of them) will be around in his next adventure, as will (I imagine) Mad Margaret.

On the other hand, whether his new lady friend appears again is another question altogether. It is to wonder, but my cap is off to Shifty Lou Anderson – there are simply no two ways about it.