Search Results for 'Ellery Queen'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Fri 12 May 2017

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

ELLERY QUEEN – The Siamese Twin Mystery. Ellery Queen #7. Frederick A. Stokes, hardcover, 1933. Pocket #109, paperback, 1941. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and paperback.

Ellery Queen’s seventh novel, and, in my opinion, by far the weakest to this point in his career. Ellery and his father, Inspector Richard, are returning from a vacation in Canada. Ellery takes a short cut, and the two find themselves cut off by a raging (is there any other kind?) forest fire.

The only refuge is the top of Arrow Mountain, where they come to the home of Dr. John Xavier, an eminent and retired surgeon, who has with him members of his family and other characters who act in the prescribed guilty manner before there is anything really to be guilty about.

As the fire races toward the mountaintop, Dr Xavier is murdered while playing solitaire and is found clutching half of a playing card in his hand — the six of spades. Later, another character is murdered, and in his hand is half of the knave of diamonds. Ellery’s interpretation of these clues are, in the first instance, weak and in the second rather tortuous, but it’s fun watching him at work.

This is the first Queen novel that does not have the usual “challenge to the reader.†Queen explains this in The Chinese Orange Mystery, without naming the novel missing the challenge, as merely an oversight, but since Ellery himself does not know who did it until the very end of The Siamese Twin Mystery — and the murderer is revealed through psychological trickery rather than ratiocination — any challenge to the reader would have been ludicrous.

Some oddities in the novel: the forest fire knocks out the telephone line, but the electricity supply never falters. Even while the house itself is burning, the light bulb in the basement, though “feeble,†continues working. There is never any mention of a generator on the premises, nor is it likely, with the house at the top of a mountain very difficult of access, that the electrical wires would be underground.

The Queens put the deck of cards from Xavier’s solitaire game in the house’s safe, but Ellery keeps the actual evidence, the six of spades, and describes the safe as a “sort of baited trap.†Yet when the murderer seems to try to get into the safe, both Ellery and his father are surprised.

Why would the murderer, they wonder, try to get the evidence from the safe when the safe didn’t contain the evidence? It does not occur to them that perhaps they had neglected to tell the murderer the safe did not contain the evidence. Besides, the murderer’s attempt is an essential device to keep the plot going, not to help the reader solve the crime.

Also, when the fire reaches the house and sets it afire, Ellery has all the characters go to the basement. Maybe this is the safest place to be when a two-story house is burning down above you and the ceiling of the basement, since we are not told otherwise, is wood, but it does seem a strange refuge.

Is The Siamese Twin Mystery worth reading despite its problems? Any Queen is worth reading, however weak it might be.

— Reprinted from

CADS 3 (April 1986) (slightly revised).

Email Geoff Bradley for subscription information.

Fri 7 Oct 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

ELLERY QUEEN – What’s in the Dark? Popular Library, paperback original; 1st printing, 1968. Dale Books, paperback, 1978. Zebra, paperback, 1985. Published in the UK as When Fell the Night (Gollancz, hardcover, 1970).

Here’s a detective novel based on the Northeast blackout of 1965, one that lasted for 13 hours and affected over 30 million people. I’d tell you about it personally, but Judy and I didn’t move to Connecticut until 1969. But it made headlines at the time, and not only does one-eyed NYPD homicide captain Tim Corrigan solve a murder mystery in the midst of the city’s shutdown, the solution depends entirely on the circumstances.

Except for one mistake, the killer could have gotten away with the death of an accountant, 21 floors up, being called a suicide. Give that he or she did, however, Corrigan has a whole floor of suspects to deal with, included a bright-eyed colleen named Sybil Graves, to whom he takes an immediate fancy.

The author behind the Ellery Queen pen name this time is Richard Deming, who wrote four of the six Tim Corrigan novels, and while What’s in the Dark? is not up to the usual Ellery Queenian standard, he proves to be an adequate creator of a detective puzzle mystery. The cousins Ellery Queen probably never used the word mammae in one of their own novels, however, nor never wrote a scene in which one character is walked in on while fumbling with the brassiere of another.

Tue 24 May 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

ELLERY QUEEN – Beware the Young Stranger. Pocket, paperback original; 1st printing, May 1965.

Back in 1961, when the first of the bogus Ellery Queen paperbacks like this one came out, in my total lack of sophisticated way, as I recall it, I said something to myself along the lines of, Gee those guys must really need the money. I bought them all, though, or most of them, but I don’t think I got around to reading many of them, no more than two or three. I don’t think I missed much, but as you and I both know full well, some must have been better than others.

This one was written by Talmage Powell, a long-time pulp writer and the creator of the better than average PI Ed Rivers paperback series. And so he was an author I was therefore familiar with at the time, but how was I or anyone else to know?

This one’s not bad — as a sample I decided to give myself earlier this past weekend — and in fact, it’s better written than most of the paperback original mysteries that were coming out around the same time. But it’s also straight as a string, with no particular surprise in the telling; even worse, it has an awfully low page count of only 156 pages, with a slightly larger than usual font size.

There’s a large back story to go along with the cast of characters in the upper middle class, or country club setting of this novel, but what it boils down to is this: distinguished diplomat John Vallancourt’s daughter is 21 and in love with a boy whose background is somewhat shady. He was questioned but released in the investigation of a young girl’s death while on spring break, for example, so Vallancourt takes it upon himself to discover a lot more about him.

But when the boy’s aunt is murdered, and he is seen leaving the scene and soon after disappearing, on the run with the daughter in tow, Vallancourt’s task takes on much more serious tones. Is the boy guilty? Or is he innocent? And will Vallancourt find the two of them in time?

Sun 1 Sep 2013

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Hello again! I won’t attempt to describe the health problems that forced me to abandon this column and just about everything else these past few months, but they seem to be behind me now and I’m ready to take up where I left off. Care to join me?

Not long before I put the column on hiatus, I learned from Fred Dannay’s son Richard that I’d made a mistake in Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection, and I can’t think of a better place to correct it than here.

On page 241 of the book I state that the 1968 Queen novel The House of Brass was written by Avram Davidson from an outline by Fred. It’s true that Davidson was commissioned to and did expand Fred’s outline to book length, but that’s only a small part of the story, which is told in full in the Dannay papers, archived at Columbia University.

Among the House of Brass documents are: (1) two different drafts of Fred’s synopsis, one running 74 pages, the other 61; (2) Davidson’s expansion of the synopsis, which runs 181 pages; (3) two copies of the 266-page version of the novel written by Manny Lee after the Davidson version was rejected; (4) two copies of the final draft of the novel, which runs 275 typed pages. These facts are indisputable, and I thank Richard Dannay for sharing them with me.

As I documented in my February column, we know from Manny’s letter to Fred dated November 3, 1958 that he was at work turning a Dannay synopsis into a new novel but had been put behind schedule by health problems. (Whether these included the onset of writer’s block remains unknown.)

We also know that the book in question was not The Finishing Stroke, which had been published much earlier in 1958 and was the last novel in what I’ve called Queen’s third period. So what happened to the book Manny was working on near the end of the year?

I can envision three possibilities. (1) Fred gave up on it completely. (2) He gave up on it as a novel and he or another writer turned it into the novelet “The Death of Don Juan†(Argosy, May 1962; collected in Queens Full, 1965). (3) Manny went back to the project after recovering from writer’s block and it was published as Face to Face (1967).

My own guess, which is speculative but (I hope!) informed, is the third possibility. With that as my premise, I offer the following timeline.

Late 1958 or early 1959 — Manny develops writer’s block and is unable to continue expanding the latest Dannay synopsis into a novel.

1961 or 1962 — A decision is made to bring in other writers to perform Manny’s traditional function.

1963 — Publication of The Player on the Other Side, written by Theodore Sturgeon from Fred’s synopsis.

1964 — Publication of And on the Eighth Day, written by Avram Davidson from Fred’s synopsis.

1965 — Publication of The Fourth Side of the Triangle, written by Davidson from Fred’s synopsis.

1966? — Davidson expands Fred’s synopsis into The House of Brass, but Fred and Manny reject his version and the project is shelved.

1966 or 1967 — Manny recovers from writer’s block and finishes his work on the project that was left incomplete back in the late Fifties. This book is published as Face to Face (1967).

1967 or 1968 — Manny completely rewrites the rejected Davidson version of The House of Brass, which is published under that title in 1968.

The final Queen hardcover novels — Cop Out (1969), The Last Woman in His Life (1970), and A Fine and Private Place (1971), whose publication Manny did not live to see — were written by the cousins without input from outsiders, Fred preparing the plot synopses as usual and Manny expanding them to book length.

As editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Fred had reprinted dozens of the pulp stories of Dashiell Hammett but just one tale by Raymond Chandler and that only after his death. Of course the vast majority of Chandler’s short fiction was too long for EQMM’s requirements, but from Fred’s point of view the most serious problem with the creator of Philip Marlowe was that, unlike Hammett, he had a pervasive tendency to get lost in his own plot labyrinths. In fact he once said that plot didn’t matter to him, only the individual scenes did.

This tendency can be seen as far back as his first published story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot†(Black Mask, December 1933; collected in Red Wind, World 1946, and in Stories and Early Novels, Library of America 1995).

Trying to make sense of this story is like trying to nail jelly to a wall. One of the main characters is Landrey, a gambler and racketeer who earlier in his life had tried to launch a Hollywood career. In those days he had had an affair with Rhonda Farr, a young beauty who had become a major star. Apparently wanting to rekindle the romance, Landrey pretends that Rhonda’s love letters to him had been stolen and has his underworld buddies demand blackmail money from her. Then he hires the story’s protagonist, a PI named Mallory, to thwart the blackmailers and recover the letters.

All these events have taken place before the story begins. Chandler opens with a nightclub scene where Mallory pretends to have the letters himself and, hoping to force the blackmailers to go after him, demands $5,000 from Rhonda. (What would he have done if she had said “Show me you have them�) Chandler never makes up his mind whether Rhonda had asked Landrey to help get her letters back.

At pages 71 and 106 of the Red Wind collection and pages 7 and 37 of the Library of America volume it seems she did, at pages 111 and 42 respectively it seems she didn’t. If she didn’t, how could Landrey have known she was being blackmailed unless he was behind it himself?

At no point does Chandler provide any details about how the letters were stolen. In fact at pages 104-105 and 36-37 respectively it’s hinted that Landrey had returned the letters long ago and that they’d been stolen not from him but from her. To make matters even more chaotic, he for no earthly reason is carrying the letters in his own pocket on the night of the action!

Simultaneously with the fake blackmail plot, Landrey has arranged for Rhonda to be kidnaped and held for ransom so that he can rescue her and earn her eternal gratitude. Apparently none of his underlings are ever privy to his overall plan, but a remark of Mallory’s — “When the decoy worked I knew it was fixed†(pp. 112 and 43 respectively) — suggests that in some mystic manner our sleuth knew the truth almost from the get-go.

Somehow, although again Chandler spares us any details, Landrey’s partner Mardonne is involved in the master scheme, and Mallory miraculously discovers this aspect of the plot too (pp. 115 and 46 respectively). Small wonder that Mardonne (on pp. 112 and 43 respectively) remarks “A bit loose in places.â€

Parsing other Chandler stories will have to be done by someone else. Life’s too short.

How better to celebrate one’s recovery from serious illness than with one of the immortal works of Michael Avallone? The Flower-Covered Corpse (1969) is rife with the scrambled sentences that are his unique claim to fame but I’ll limit myself to a handful. The “I†in these quotations is New York PI Ed Moon, who is to detectives what Ed Wood was to directors.

I had never heard of Louis La Rosa. Didn’t know him from Robert J. Kennedy.

Blood played tag in my little grey cells.

“….Hep you may be but you are unitiate….â€

The mad evening had come to its final, inexorable totem pole of weird unreality.

More marbles scattered across the floor of what was left of my brain.

Right after War Two, he had plunged into the Police Academy bag and come up with an apple pie in each hand.

I didn’t have a client except myself and my own neck.

He tried to smile, still huddling his lovely fortune cookie.

Femininity and Melissa Mercer are blood sisters.

The .22 spit like a sneeze.

I said a handful and a hand has five fingers so I guess I should have stopped halfway through my list. But there’s something about Avalloneisms that almost forces me to say — again and again and again — “Just one more.†I hope you didn’t mind too much.

Mon 4 Feb 2013

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Another baffling Ellery Queen mystery! One of the most fascinating letters from Manfred B. Lee to Fred Dannay that Joseph Goodrich didn’t include in his book BLOOD RELATIONS is dated November 3, 1958. More precisely, it’s dated “Nov. 3†with the year added in brackets, presumably by Goodrich.

Right at the start Manny tells Fred: “The novel will not be ready on Dec. 1. Its status is as follows: About 2/3 of the rough draft was done quite a while ago, but I found large sections of it unsatisfactory…and began doing them over.†Then he starts describing the health problems that have kept him from finishing this novel.

Which novel is he talking about? It can’t be THE FINISHING STROKE, which was published very early in 1958. But Manny never wrote another novel from a Dannay synopsis until the late Sixties when he overcame the writer’s block that had handicapped him for almost a decade.

Is it possible that the bracketed date is a mistake, that the letter was actually written a year or two earlier? No! About halfway through the document Manny talks about the live 60-minute Ellery Queen TV series, then starring George Nader. That series was broadcast only during the 1958-59 season. Manny even mentions that the episode shown the previous Friday was based on perhaps the finest of all Queen novels, CAT OF MANY TAILS (1949). We know that the air date of that episode was October 31, 1958, and Manny even mentions that it was shown on Halloween night. There’s not a chance in a trillion that this letter was written at any time other than what its dateline says.

What then are we left with? With the distinct possibility that there exists somewhere an “unknown†Ellery Queen novel, perhaps finished, perhaps unfinished. If so, what a find!

There are other possibilities, but they seem most unlikely. One that I considered and quickly rejected is that the book Manny was working on late in 1958 was published in 1963 as THE PLAYER ON THE OTHER SIDE. If Manny became afflicted with writer’s block soon after writing this letter, Fred might have let his synopsis sit for a few years and then given it to Theodore Sturgeon, who expanded the outline into that novel.

What rules out that theory? Since we know that Manny was working on the book “quite a while†before November 1958, Fred’s synopsis must have been completed earlier. But the outline for THE PLAYER ON THE OTHER SIDE can’t possibly predate the release of Hitchcock’s PSYCHO (1960), to which the plot of PLAYER owes so much. Even assuming that the influence on PLAYER comes not from the movie but from Robert Bloch’s novel of the same name (1959), the time element still eliminates PLAYER as the outline Fred prepared a year before Bloch’s book was published.

Let’s explore another possibility. Might Fred have eventually decided that the novel Manny was working on in 1958 — and may or may not have finished — should be cut down to novelet length? There’s one Queen novelet which just might fit the time frame: “The Death of Don Juan,†which was first published in Argosy, May 1962, and is collected in QUEENS FULL (1965). I can find no positive evidence in support of this theory but nothing against it either.

When speculation fails, search for facts. I recently emailed Fred’s son Richard Dannay, asking if he had ever seen a manuscript that fit the vague description in Manny’s letter. (If only he had left a hint or two as to what the plot was about!) Richard said no but admitted the possibility that he and his brother Douglas had overlooked something while sorting through their father’s huge accumulation of manuscripts and papers. There the trail ends — unless some intrepid literary sleuth spends months combing through every paper in the Dannay archives at Columbia University. Any volunteers?

For three months I’ve resisted offering another assortment of quotations from the one and only Mike Avallone, but I can’t hold back any longer. Here come some more cubic zirconia from the Ed Word of the written wood, all from THE SECOND SECRET (1966, as by Edwina Noone), the same epic from which I culled quotations back in November. With the iron self-control of the Spartan boy who hid the fox under his tunic I shall limit myself to six new ones.

The biggest conflagration she had ever seen were the playful bonfires set by the children of Englishtown on holidays. (20-21)

The poor Freneaus. For all their wealth and position, they certainly had not had a barrel of skittles. (22)

A peach that hung in their midst for years had been abruptly plucked from the communal tree and now no one knew what was in store for her. (46)

She stood on the boarded sidewalks of the town, staring after the carriage, a bouquet of tulips sprayed over her worn fingers. (46)

As close as Clara was now, both physically and relationally, she was as distant and remote as the stars… The gossamer veil, netting Clara Freneau’s wantonly darkish face was insufficient to completely mask the hostility of the woman. (47)

“It was such a beautiful ceremony. Thank you for being bridesmaid.â€

“You’re welcome, my dear… You may thank my late father’s sword also since it served as your best man.†(47)

Thank you, Mr. Sword. And thanks also to Mike Avallone, whose wacko way with words can lift me out of the blackest moods.

Fri 11 Jan 2013

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

During 2012 I spent more time on Ellery Queen than on any other author or character. I hadn’t planned to tackle another Queen project so soon after completing The Art of Detection, but over the holidays I did. A few months ago Joseph Goodrich, editor of the book of selections from the correspondence between Fred Dannay and Manny Lee that was published as Blood Relations (2012), had generously sent me a 97,500-word document containing virtually all of Manny’s letters to Fred, far more material than there was room for in the book.

I had done some organizing and rearranging and had added a number of bracketed annotations explaining obscure points in the letters but I hadn’t yet made myself thoroughly familiar with the material. This I set out to do over the holidays. Some remarkable discoveries rewarded me. Here’s one of them.

Among the many problems Fred had to deal with as founding editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine was figuring out who would take over in that capacity if he were to die or become disabled. Manny had no interest in short detective fiction and very little editorial experience, but neither man relished the prospect of the magazine being run by a stranger. So, for a short time anyway, Manny was sent some of the stories submitted to EQMM and undertook to write comments on them for Fred.

Among those he evaluated was a 57-page manuscript by Charlotte Armstrong (1905-1969), who was best known for the spectacularly successful suspense novel The Unsuspected (1946). “Night Mustn’t Fall†begins when a dog is found poisoned in a quiet suburban neighborhood one summer Saturday afternoon. A young visitor named Mike Russell tries to help its 11-year-old owner and his sixth-grade buddies find out whether the poisoner was the homeowner on whose lot the dog was found — and with whom most of the neighborhood kids had had run-ins — or someone else.

Manny found many things wrong with the tale. In a letter dated April 29, 1950, he agreed with Fred that the story was “at times too sentimental and gushy†and that its “psychological and emotional aspects are over-inflated.†He also considered it far too long. “I could guarantee to take this manuscript as it now stands, without changing one word…, and cut its 57 pages down to, say, 30 (or less!) and thereby improve it one thousand percent. It is repetitious throughout, and whatever is good in the writing is blunted by the sheer bludgeon blows of over-and-over-again.â€

But, he went on, “the story is worth saving. It has its potentialities, certainly, not the least of which is the kernel of its message, which is that truth is a hard job and that children have to be trained to look for truth … and that if more children were so trained, this would be a far different adult world.â€

After some conversations with Fred, Armstrong resubmitted her story as â€The Enemy.†It was published under that title (EQMM, May 1951), won first prize in the magazine’s annual short-story contest, and a few years later became the basis for a feature-length movie (Talk About a Stranger, 1954). The story is included in Armstrong’s collection The Albatross (1957).

From reading the published version it’s clear that she thoroughly cut, revised and improved the manuscript Manny read. The repetitious writing has been eliminated, the emotions are tightly controlled as in Hemingway or Hammett. Manny had complained that altogether too many people in the neighborhood were able to tell Russell and the boys at exactly what time they had seen the dog, but apparently Fred wasn’t bothered by this point.

What puzzles me is the number of plot flaws that survived the revision. One minuscule problem: The story needs to take place on a Saturday because the boys couldn’t be on the scene if it were a schoolday. But near the end we learn that one of the witnesses who noticed the dog before its death was a girl had a sore throat that day and was sitting on her porch, “waiting for school to be out, when she expected her friends to come by.â€

A much more serious flaw to my mind is in the solution, which I must reveal in part if I’m to discuss the story seriously. The man on whose property the dog’s body was found lives with his wheelchair-bound wife and crippled stepdaughter. At the climax we discover that when he went out to play golf that Saturday morning, the younger woman, who cooks for the three of them, gave him a lunch box containing hamburger sandwiches laced with arsenic.

Unable to stomach her cooking, the lucky man ate out. But instead of disposing of the burgers in a trash can like any normal person, he brought them home and threw them onto the empty lot next to his house, where the unlucky dog found them and died minutes later! “The Enemy†is a fine story overall, but was it the best choice for first prize winner?

I hadn’t read one of John Rhode’s detective novels about Dr. Lancelot Priestley in several years. Over the holidays I decided it was time to revisit that curmudgeonly old amateur of crime and chose Death on the Boat Train (1940), which I’d first read in my teens but had completely forgotten long before the 21st century began.

At the end of a train’s run between the English Channel port of Southampton and London’s Waterloo Station, the body of a poorly dressed man is found in a first-class compartment and Inspector Jimmy Waghorn of Scotland Yard is summoned. The cause of death turns out to be a poison called ricin which was injected into the man’s butt (which Rhode discreetly calls “the right-hand side of the backâ€) with a hypodermic syringe.

The victim turns out to be steel magnate Sir Hesper Bassenthwaite, who for some obscure reason had chosen to travel on the Channel steamer from the island of Guernsey to Southampton and then on the Southampton-Waterloo boat train more or less in disguise. Since Sir Hesper had had a compartment to himself both on the steamer and the train, how could anyone have injected poison into his kiester without his knowledge? In due course Waghorn and his boss, Superintendent Hanslet, drop in on Priestley to discuss the case over dinner and drinks and their host, true to form, offers one inspired suggestion after another.

Death on the Boat Train is among the more solidly plotted Rhodes but, as always, the characters are wooden and the prose leaden. (In the novel’s innumerable Q&A sequences anyone’s answer to a question is followed by the words “he [or she] replied.†It was my noticing that the same linguistic oddity infested the detective novels of another Golden Ager, Miles Burton, that allowed me to deduce, way back in the Pleistocene era, that Rhode and Burton were the same man.)

What most surprised me about the book is that amid the dry-as-dust exposition and dialogue are a few gaffes almost in the Mike Avallone league. “‘I seem to remember that at one time you knew how to make unprotected females unbosom themselves.’†(219) “She returned her shoulder to him and read a few lines of her magazine.†(221) “His glance wavered round the room as though seeking some form of liquid refreshment.†(273) “Late that night a very weary Jimmy unbosomed himself into Diana’s sympathetic ears.†(281)

Could this most staid and stolid of English crime novelists have been fixated on a certain body part which shall be nameless?

Fri 7 Dec 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

While working on the last tedious chores in connection with ELLERY QUEEN: THE ART OF DETECTION, which will come out in January, I expected to devote my final column of the year to someone besides EQ. Almost anyone. But back in October Joseph Goodrich — a name you’re familiar with if you read this column regularly — emailed me a long document consisting of a large number of letters from Manny Lee to Fred Dannay that for space and other reasons he hadn’t included in BLOOD RELATIONS, his collection of the correspondence between the cousins whose byline was Ellery Queen.

Many of these letters were undated, those that had dates were often out of chronological order, typos abounded, but — Wow! For the next few weeks I alternated between slogging away at the ART OF DETECTION index and working on the Lee document: reorganizing, trying to date the letters that were dateless, adding material in brackets to explain (where I could) who or what Manny was talking about, doing pretty much the same things Joe Goodrich himself had done so well in BLOOD RELATIONS.

One item I discovered I was able to work into the text of my book at the last minute. The earliest letter in the document dates from very late 1940. Fred Dannay had recently been discharged from the hospital after suffering serious injuries in an auto accident. Manny’s letter mentions that among the people who had called asking about Fred was one Laurence Smith, whom he identifies as the ghost writer behind the then recently published novelization based on the movie ELLERY QUEEN, MASTER DETECTIVE (1940).

Laurence Dwight Smith (1895-1952) has long been forgotten but a few minutes with Google brings him back to life. Under his own name he wrote four or five whodunits, several mystery/adventure books for young adults, and a few nonfiction books like CRYPTOGRAPHY: THE SCIENCE OF SECRET WRITING (1943) and COUNTERFEITING: CRIME AGAINST THE PEOPLE (1944). His short story “Seesaw†was one of the first originals to be published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (July 1942). What else he may have written under other bylines, or even whether he ghosted the other EQ movie novelizations, THE PENTHOUSE MYSTERY (1941) and THE PERFECT CRIME (1942), remains unknown.

It’s long been known that Fred Dannay devised the plots for the Ellery Queen novels, stories and radio dramas and Manny Lee did the actual writing — and also that at a certain point in the nine-year life of the radio series Fred, whose wife had been diagnosed with cancer that eventually (on July 4, 1945) killed her, couldn’t perform his function any longer.

Exactly when that happened would remain unclear today except for the Lee document. In a letter written on June 30, 1948, shortly after the Queen radio program was cancelled, Manny mentions that he had taken over the series “in January of 1944, when you dropped out of active work.†For most of that year, Manny reminds Fred, he made do by recycling 30-minute scripts from earlier seasons and condensing some of the original 60-minute scripts (1939-40) to half-hour length.

Eventually, Manny says, he “began doing originals from bought material.†When? In October 1944, at the start of the program’s fifth season. Does this mean that every new weekly episode from then on was based on a plot synopsis by someone other than Fred? Not at all! Manny’s correspondence with Anthony Boucher informs us that Fred was several synopses ahead of schedule at the time he dropped out.

These Manny squirreled away and fleshed out into scripts over the next two years, the last one (“The Doomed Manâ€) being broadcast late in August 1946. But most if not all of the new scripts for the fifth season were probably based on “bought material.â€

Bought from whom? For the first several months of the new regime, the plots were devised by a long forgotten scribe named Tom Everitt. Even in the age of the Internet almost nothing is known about this man, but we know a great deal about what Manny thought of him because his letters to Boucher are full of snarky remarks about Everitt’s competence and character. On May 24, 1945, he described himself as “hating [Everitt’s] smug, treacherous guts†and Everitt’s recent plot synopses as “sloppier…even than usual….â€

His letters to Fred Dannay in the Lee document offer more of the same. On November 4, 1947, he called Everitt “a son-of-a-bitch†who at the rate of $400 per synopsis got “tremendously overpaid†even though “the bulk of the creative work was done by me, out of sheer necessity….[Y]ou don’t know the things…that bastard has been saying and is still saying in the advertising business about his ‘part’ in the Queen show. There is no protection against his kind of conscienceless and unscrupulously shrewd self-propaganda….â€

Manny would love to have worked exclusively with Boucher but Tony was unable to come up with complex Ellery Queen plots on a one-a-week basis and Manny had no choice but to continue buying from Everitt until late in the program’s radio life.

At least 33 of the Queen scripts between January 1945 and September 1947 came from Everitt raw material and are identified as such in my book THE SOUND OF DETECTION (2002). Most of the scripts between October 1944 and mid-June 1945, when the first episode based on a Boucher plot was broadcast, were probably derived from Everitt too. “Cleopatra’s Snake†(October 12 and 14, 1944) finds Ellery as backstage observer at a live production of ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA for experimental TV when the genuine poisonous snake being used in the death scene (yeah, right) bites to death the actress playing Cleopatra.

In “The Glass Sword†(November 30 and December 2, 1944) Ellery tackles the case of the circus sword swallower who died when the sword in his stomach broke while the lights were out. These concepts strike me as way too wacko to have come from the mind of Fred Dannay. Therefore they almost certainly came from Everitt.

The vast majority of Everitt-based EQ episodes have never been published as scripts and don’t survive on audio. But it now seems quite possible that one of them was mistaken for a Dannay-based episode and published a few years ago — as the title story in the collection THE ADVENTURE OF THE MURDERED MOTHS (Crippen & Landru, 2005). The episode with that title was broadcast on May 9, 1945. The plot is nowhere near as off-the-wall as those of “Cleopatra’s Snake†or “The Glass Sword†and therefore might be one of those Fred completed before he left the series. We just don’t know. Maybe we never will.

Mon 17 Sep 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

ELLERY QUEEN – The Spanish Cape Mystery. Frederic A. Stokes, hardcover, March 1935. Pocket #146, 1st printing, February 1942; 17th printing, May 1951 (shown to the right). Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

The titular Spanish Cape is a small hunk of land sticking out into the ocean somewhere along the North Atlantic seaboard. There is only one home there, that of Walter and Stella Godfrey and their family, along with assorted summer guests, none of whom knew him before they were invited, nor he them. Which is a good way to get a good detective puzzle started, but wait, you haven’t heard how this mystery really gets going.

Which is with the kidnapping of Rosa, Stella and Walter’s daughter, along with Stella’s brother and Rosa’s uncle, by a giant one-eyed pirate-like figure who has made a big mistake. By his own account, what he really meant was to drag a fellow named John Marco out of the house and dump his body at sea. On whose orders? After the error was discovered, it must have been the person who followed through with Marco’s death back at the Godfrey manor.

A death, however, which is even more puzzling. Marco is found strangled on an outdoor terrace, totally nude except for a cape, hat and walking stick. Most of the Ellery Queen detective puzzles are larger than life, and this one, as you may have surmised, is no exception.

Ellery is called upon to lend a hand while on vacation. Inspector Queen, however, is not along with him. Working with Ellery on this case is Judge Macklin, a long time friend whom he is traveling with, and the local police, headed up by one Inspector Moley, who growls in frustration about as well as Ellery’s dad does when the deduction seems to get derailed, so the latter is not particularly missed.

As intricately plotted as any of Ellery’s early cases, this ninth case in novel form (and the last with this particular title pattern), finds Ellery a lot looser and less formal in his approach, with his pince nez mentioned only once, if I recall correctly. (I may be wrong about this.)

Ellery Queen, the authors, still don’t know much about proper police procedure, nor does the occurrence of sudden, unexpected death cause nearly as much stir as surely it would in real life, but that’s not the point. This is a puzzle mystery, through and through, which each piece of the jigsaw needed to point the finger in the end at only one suspect, and one suspect only.

I enjoyed it all very much, thank you, even though I decided very early on who the killer was, and even though I was right about that, I failed to catch the significance of the naked body of the not-very-well-liked Mr Marco. Having thought about it now for 24 hours since I finished the book, there’s simply no way for me to write around it. The killer’s behavior was simply too bizarre for me.

It’s a shame that all of Ellery’s deductions are based on such a single weak point, but if you can give the authors the benefit of the doubt, everything else snaps into place in absolutely perfect fashion.

Sat 4 Aug 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

The golden oldie I picked to reread last month was The Bowstring Murders (1933), the only John Dickson Carr novel ever published under the byline Carr Dickson. I wouldn’t rank it among Carr’s top ten or even the top thirty but thought it was on the whole satisfactory, taking place almost entirely in an eerie 15th-century Suffolk castle full of the Poe-like atmosphere that the young Carr loved to generate.

Is it truly golden? According to Doug Greene’s biography The Man Who Explained Miracles (1995), Carr wrote Bowstring in New York “at white-hot speed†after his English wife Clarice discovered she was pregnant and also in order to finance a long visit to England for the family.

Greene calls the novel “badly flawed .. John Gaunt [the criminologist who solves the murders] is sharply drawn, but the plot…is unconvincing.†He correctly describes the explanation of the seemingly impossible murder of Lord Rayle as “a creative variation of the solution in [Carr’s first novel] It Walks by Night…â€

He was surprised by “how many mistakes Carr makes about England†but the ones he cites strike me as trivial: the servants “all speak a strange sort of Cockney†and after Lord Rayle’s murder the Bowstring footman fails to address the dead man’s son and successor to the title as “Your Lordship.â€

Greene also mentions “some sloppy lines†in the book but quotes only one, from Chapter 12: “With one gloved hand, he dived behind the body.†Does that sentence rise to the lofty heights of an Avalloneism? Personally, I don’t think so.

What bothered me most about the plot (am I giving away too much here?) is that, in order for the crucial gimmick to work, a cowled “white-wool monk’s robe†of the sort which the “more than half-cracked†Lord Rayle wore while wandering around Bowstring must be concealed by the murderer in an ordinary briefcase.

S. T. Joshi in John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study (1990), is no fonder of The Bowstring Murders than Doug Greene. He calls the novel a “confused and shoddily written work†and both the book and its protagonist “spectacular failures.†(Greene, as we’ve seen, disagrees with Joshi about John Gaunt.)

Joshi’s main complaint is that “the solution depends vitally upon our knowing the exact plan of the house, which is not provided.†Obviously there was no such plan in whatever edition Joshi read, and there’s none in the only edition I have (Berkley pb #G-214, 1959).

But there are several references to the local inspector making a drawing of Bowstring Castle, and I have a hunch that the sketch does appear in the original hardcover edition. If someone reading this column can tell me whether I’m right or wrong, please speak up.

If anyone decides to read the novel on the strength of this discussion, they should first go here and download the detailed diagram of the castle that Wyatt James, 1944-2006 (known to Internet mystery fandom as Grobius Shortling) kindly prepared for Carr fans who don’t have a copy of that first edition. And, if my hunch is wrong, even for those who do.

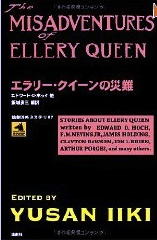

In my mailbox recently was a book that was sent from Japan but has an English as well as a Japanese title: The Misadventures of Ellery Queen. This 400-page anthology, edited by Yusan Iiki and published by Ronsosha Ltd. Of Tokyo, brings together a huge assortment of parodies and pastiches of the immortal EQ, written by such authors as Jon Breen, Ed Hoch, James Holding, Josh Pachter, Clayton Rawson and, if I may be so immodest as to say it, me. (Anyone remember “Open Letter to Survivors�)

The most recent story in the volume, and probably the finest Queen pastiche ever written, is “The Book Case†(EQMM, May 2007) by Dale Andrews and Kurt Sercu, in which Ellery at age 100 proves that his body may be feeble but his mind is sharp as ever.

Years ago Josh Pachter put together an anthology, also called The Misadventures of Ellery Queen, but could never find a publisher for it. The appearance of this new volume, coupled with the failure of Pachter’s book to find a home, provides an excellent demonstration of how tall Queen still stands in Japan and how deeply he’s sunk into oblivion almost everywhere else.

Thinking about the role of genetics in mystery fiction, we at once conjure up the DNA testing scenes in countless TV forensic series. But the subject has also figured in the Golden Age of the whodunit. In the 60-minute radio drama “The Missing Child†(The Adventures of Ellery Queen, CBS, November 26, 1939).

Ellery’s solution hinges on his assertion that it’s impossible for two blue-eyed parents to have a brown-eyed child. That was a common belief at the time, and was also crucial to the solution in an Agatha Christie story of the same decade (“The House at Shiraz,†collected in Mr. Parker Pyne, Detective, 1934).

But it’s flatly not true, as Fred Dannay and Manny Lee must have discovered sometime in the ten or eleven years following broadcast of the drama. How do I know? Because the fact of its falsity is central to one of the later EQ short stories, “The Witch of Times Square†(This Week, November 5, 1950; collected in QBI: Queen’s Bureau of Investigation, 1955).

Genetics mistake and all, the original script is included in that indispensable collection of Queen radio plays The Adventure of the Murdered Moths (Crippen & Landru, 2005).

In a column posted back in 2006 I waxed nostalgic for a paragraph or two about Boston Blackie (1951-53, 58 episodes), starring Kent Taylor in perhaps the earliest and certainly one of the finest action-detective TV series, most episodes featuring one or more elaborate chase-and-fight sequences shot on Los Angeles streets and locations.

Eighteen of the 26 segments that made up the first season were directed by Paul Landres (1912-2001), whose action scenes, brought to life by master stuntmen Troy Melton and Bill Catching, were of eye-popping visual quality, especially considering that each episode was shot in two or at most three days.

Until recently it’s been next to impossible to find decent VHS or DVD copies of Blackie segments, all of which have long been in the public domain. Which is why I was delighted to discover recently that at least twenty episodes are now accessible on YouTube — and that many of them were digitally restored last year.

I especially recommend the earliest segments like “Phone Booth Murder†(#2), “Blind Beggar Murder†(#5), “The Cop Killer†(#6), and “Scar Hand†(#11), all directed by Paul, whom I met when he was in his mid-eighties and who was the subject of a book of mine that came out about a year before he died.

Paul would have been 100 this month, and to celebrate his centenary I’ve prepared a DVD tribute that will be presented at the Mid Atlantic Nostalgia Convention in Hunt Valley, Maryland on August 11.

In one of the tapes I made with Paul he vividly described an accident that took place while he was shooting the climax of “Phone Booth Murder.†His description is now preserved on my DVD, accompanied by the climactic sequence itself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJ6voB6ADfE

If any readers of this column check out this episode and are interested in what went wrong and how Paul responded to the crisis, I’ll include his comments in my September column.

Fri 13 Jul 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

It’s official, gang. I’ve just signed a contract with Perfect Crime Books for the publication of — how shall I describe it? It may not be quite as hefty as my book on Cornell Woolrich, whose title I adapted for the titles of these columns, but it will certainly qualify as a literary doorstop.

Back in the 1980s I wanted my Woolrich book to answer almost any imaginable question about the haunted recluse I’ve called the Hitchcock of the written word. Now as I slipslide into senility I want my new book to be just as comprehensive about the two first cousins from Brooklyn who wrote some of the most complex and involuted detective novels of the genre’s golden age.

Are you familiar with everything bagels? This tome will be, I hope, the Everything Book on Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Its tentative title is Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection.

I think I heard a question from cyberspace. “Hey, didn’t you do that book already, back in the Watergate era?†Well, sort of. But as I got older I became convinced that I hadn’t done all that good a job.

Fred Dannay was the public face of Ellery Queen, and in the years after we met he became the closest to a grandfather I’ve ever known, but I never really got to know the much more private Manny Lee. He and I had exchanged a few letters, and we met briefly at the Edgars dinner in 1970, but he died before we could meet again.

Because of his untimely death Royal Bloodline inadvertently gave the impression that “Ellery Queen†meant 90% Fred Dannay. One of the most important items on my personal bucket list was to do justice to Manny.

Thanks largely to the memoirs published by his son Rand Lee, and to the Dannay-Lee correspondence (in Blood Relations, published early this year by the same Perfect Crime Books that will issue The Art of Detection), and to the correspondence between Manny and Anthony Boucher, which is archived at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, I’ve come to a much clearer understanding of Manny, of who he was and how he lived and worked and thought.

The Art of Detection improves on Royal Bloodline in all sorts of ways but for me this one is the most important. In addition it provides much more detail on subjects like the EQ radio series (1939-48) and the decades-long interaction between the cousins and Boucher.

And of course it covers all sorts of subjects that postdate the early 1970s, like the EQ TV series with Jim Hutton, and Fred’s third marriage and last years and death. And there will be a number of photographs never seen before.

When I first discovered the Ellery Queen novels, that byline was a household name. It still was when I first met Fred Dannay. I can’t believe that in my lifetime the Queen name has (except in Japan) been so completely forgotten. Maybe, just maybe, with the publication of Blood Relations this year, and of my book next year, and of Jeffrey Marks’ biography-in-progress two or three years from now, I’ll live to see the return of Ellery Queen to the public eye.

On June 5, at age 91, Ray Bradbury died. In his own field he was and will remain a giant. As far as I can determine, among the hundreds of authors whose work Anthony Boucher reviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle during and for a while after World War II, he was the last one standing.

Reviewing Bradbury’s Dark Carnival collection in his Chronicle column for June 22, 1947, Boucher called the author “the most fascinating and individual talent to appear in the fantasy field for a long time….[T]here’s no telling what may come of this still very young man.â€

During his early and middle twenties Bradbury also wrote stories for crime pulps like New Detective, Dime Mystery and Detective Tales. Was Boucher familiar with them?

“For years,†he wrote in his Dark Carnival review, “I have been prowling newsstands and buying any magazine with a Ray Bradbury story.†Observe that that sentence isn’t limited to fantasy-horror magazines.

In any event Boucher was long dead by the time Bradbury’s earliest crime tales were collected in the paperback original A Memory of Murder (Dell, 1984). We know that Bradbury was a great admirer of Cornell Woolrich, and he may well have been the first writer for whose short crime fiction Woolrich was the model and polestar.

Woolrich never once used a series character. After two tales about a character called the Douser — for my money the weakest of the fifteen in the collection — Bradbury followed that lead. He never approached Woolrich’s mastery of pure edge-of-the-chair suspense but, for a kid in his middle twenties, did a noble job creating noir atmosphere Woolrich style.

The more you’re at home in Woolrich, the more you feel a sense of deja vu when you read Bradbury’s stories. “Yesterday I Lived!†(Flynn’s Detective Fiction, August 1944) echoes Woolrich’s “Preview of Death†(Dime Detective, November 15, 1934; collected in Darkness at Dawn, 1985) in the sense that both are about a Hollywood plainclothesman of low rank investigating the death of a lovely actress while she’s filming a scene:

“He went out into the rain. It beat cold on him… Cleve clenched his jaw and looked straight up at the sky and let the night cry on him, all over him, soaking him through and through; in perfect harmony, the night and he and the crying dark.â€

In that paragraph and countless others in these stories, it’s obvious whom Bradbury is channeling.

Sometimes Bradbury offers his own take on a Woolrich springboard situation, for example in “It Burns Me Up!†(Dime Mystery, November 1944), which tracks Woolrich’s “If the Dead Could Talk†(Black Mask, February 1943; collected in Dead Man’s Blues, 1947) in that each is narrated in first person by a corpse.

Sometimes there’s an echo even in the titles, for example “Wake for the Living†(Dime Mystery, September 1947), which evokes Woolrich’s classic “Graves for the Living†(Dime Mystery, June 1937; collected in Nightwebs, 1971).

Bradbury’s prose tends to be more shrill and lurid than Woolrich’s, and pockmarked with exclamation points — even in the titles! — as Woolrich’s never was, but the influence is crystal clear.

In his introduction to A Memory of Murder, Bradbury was quite modest about his contribution to our genre:

“I floundered, I thrashed, sometimes I lost, sometimes I won. But I was trying … I hope you will judge kindly, and let me off easy.â€

This old jurist has done just that, and urges others who reread these stories to bang their gavels softly.

“Sweet, dear, impossible man. I wonder who he’s making love to now. I wish it were me. I have the education and breeding to appreciate a gentleman like he is.â€

No one seems to have guessed who wrote those ludicrous lines, supposedly from the viewpoint of an educated woman, that I quoted in my last column.

Maybe that’s because in a sense I was trying to mislead. The malapropisms from Keeler, Avallone, John Ball, William Ard and myself were false clues in the Carr-Christie-Queen manner, playing completely fair with the reader but designed to give the impression that the sixth quotation was by a sixth person.

In fact it wasn’t. The perp, as at least one reader should have figured out, was the ineffable Avallone. Here’s another from the same inexhaustible cornucopia:

“Wolfman Dakota, born of an Apache mother and a Texan rancher, with bronze skin and hot blood in his veins … killed with a weapon unique in crime-land circles. A blowgun filled with poison-tipped darts. A leftover from his Apache heritage….â€

Ah yes, who can forget the climax of Stagecoach, with those damn red savages chasing the coach across the salt flats, blowing their poison darts at the Duke and Claire Trevor and all the other passengers?