Search Results for 'Henry Kane'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 1 Jun 2016

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

If I had gone to New York for this year’s Edgars dinner, I would have known a few weeks sooner. As it was, I read the news in the program booklet, which reached me in the mail a few days ago. Among the MWA members who died in 2015 was one I knew. His name was Charles Runyon. To friends he was Chuck.

He was born in rural Missouri in 1928 and died last June, a few hours short of his 87th birthday. He was well-known in the science-fiction field and also as a writer of paperback crime-suspense novels like THE PRETTIEST GIRL I EVER KILLED (1965) and the Edgar-nominated POWER KILL (1972). My first contact with him was more than three decades ago, probably in the year that will be forever linked with George Orwell. His first story for Manhunt had been adapted into an episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, and I wanted to include it in my anthology HITCHCOCK IN PRIME TIME (1985), which brought together twenty tales that had served as episodes for that long-running series, with each author who was alive and willing being offered a bonus if he or she would write an afterword for the book. (For those who were unwilling or dead I did the honors.) Chuck was both alive and willing and contributed by far the longest afterword of the twenty.

A few years later, on my way back from a gig somewhere west of St. Louis, Chuck invited my late wife and me to stop off in the small Missouri town where he was then living and visit with him. We did. I remember it was a Sunday morning. While I was using the facilities, Patty started asking Chuck about his work, and when I came back to the conversation she told me excitedly that Chuck had just told her he’d ghosted three of the paperback originals published in the Sixties as by Ellery Queen.

For me this was tremendous news. I had been trying to track down the authors of all those faux-EQ paperbacks but was still missing some. Suddenly out of the blue, three more pieces of the puzzle had fallen into place. Patty: Thank you, thank you, thank you.

The Queen paperback originals had come about during the years when Manny Lee, whose function in the partnership had been to expand his cousin Fred Dannay’s lengthy synopses into novels, was suffering from writer’s block. At the same time the literary agency representing the cousins was looking for ways to expand the Queen readership beyond the confines of formal detective fiction. The result was an arrangement whereby other clients of the agency would be paid a flat fee per book to write paperback novels — standalones, without Ellery or the other Queen series characters — to be edited by Manny and published as by Queen.

It was a terrible idea, which Fred Dannay strongly opposed, but in view of Manny’s situation and the large family he had to support, there seemed no alternative but to agree. Between 1961 and 1972 a total of 28 books ghosted by nine authors were published under this arrangement. In order of their assumption of the Queen byline, the authors were Stephen Marlowe (1), Richard Deming (9), Talmage Powell (6), Henry Kane (1), Fletcher Flora (3), Jack Vance (3), Chuck Runyon (3), Walt Sheldon (1), and Edward D. Hoch (1). Jack Vance (1916-2014) was the longest-lived of the nine but Runyon was the last man standing.

He had authored a few paperback original crime novels for Fawcett Gold Medal and some hardboiled stories for Manhunt when he took on the Queen mantle, debuting with THE LAST SCORE (Pocket Books pb #50486, 1964), which Anthony Boucher in the Times Book Review (January 24, 1965) rightly called “a straight-out adventure thriller.†Tough tourist guide Reid Rance is hired to chaperon a wealthy teen-age sexpot on a journey through Mexico, a country with which Runyon was intimately acquainted. When the girl is kidnapped and held for ransom, our macho protagonist doesn’t bother to notify the authorities but launches a one-man war against the abductors. The background is vividly evoked, the descriptions of a marijuana “high†ring true, and despite some implausibilities in the slender storyline this is a model of men’s-magazine adventure fiction. “Good violent excitement,†said Boucher, “tightly told.†But — an Ellery Queen novel???

Runyon brought another macho action yarn under the EQ umbrella in THE KILLER TOUCH (Pocket Books pb #50494, 1965). A tough Florida cop, tormented by a wound and his guilt at killing a teen-ager in line of duty, comes to a tropical island resort where a gang of thieves headed by a doom-haunted sadistic intellectual has just moved in after pulling off a diamond robbery.

The writing is vivid, the incidents lurid, the climax rushed, and Runyon crams in enough torture scenes, sex teasing and carnage to satisfy the most rabid. Was Boucher turned off by all the bloodletting? For whatever reason he chose not to review this one.

Roughly four years passed before Runyon sailed under the EQ flag for the last time. KISS AND KILL (Dell pb #4567, 1969) is a tornado-paced novel of pursuit and menace complete with sex, sadism, machismo and a psychopathic creep. When a young Chicago housewife vanishes after returning from a tour of — here we go again! — Mexico, her distraught husband and a local PI take up the trail and soon discover that everyone else on that tour has either disappeared or suffered a violent death.

About halfway through the book the action shifts to south of the border and the two urban male protagonists, joined by a woman photographer from St. Louis, become instant experts at guerrilla warfare against professional killers. But neither this implausible development nor the recycling of tough-guy fiction’s most overused climactic “surprise†diminishes the pure headlong storytelling drive that makes Runyon’s ultimate men’s-mag adventure unputdownable. Boucher didn’t review this one either but not by choice: he had died the year before it came out.

From the Runyon file in one of my cabinets I discovered something that thanks to old age I had totally forgotten: Chuck and his wife had actually stayed with Patty and me around Christmastime one year, and we had hosted a little party to introduce him to some other St. Louis-area mystery writers. Several of his novels are on my shelves, a few of them inscribed to me, probably during his visit. If those who are interested in the books he wrote under his own name follow this link to Steve’s primary Mystery*File website for an interview conducted several years ago by Ed Gorman. I strongly recommend it to anyone who wants to know more about Chuck’s life and work. I only wish I had known him better.

Tue 9 Feb 2016

PETER CHAMBERS – Downbeat Kill. Abelard-Schuman, US, hardcover, 1964. First published in the UK by Robert Hale, hardcover, 1963.

There was a time — this was long ago — when I thought there was somehow a connection between the author Peter Chambers, and the private eye character Peter Chambers whose adventures were told by Henry Kane. That the author Peter Chambers’s most frequently used character was also a PI (named Mark Preston) made such a connection all the more plausible. So so I thought.

It turns out, as has been well known for many years now, that even though his character’s stories take place in California, Peter Chambers the author is as British as they come, and there is no connection to Henry Kane or his character whatsoever. Chambers’ real name is Dennis Phillips (1924-2006), and while having written only one crime novel under his own name, he wrote almost 40 as Chambers — most but not all with Preston — one as Simon Challis, five as Peter Chester, and thirteen as Philip Daniels.

Very few of them have been reprinted in this country. Downbeat Kill is one of only eight of Preston’s cases to have been published over here. On the basis of this sample of size one, in spite of this overall rather sizable output of 36 in all, I find it really doubtful that I will find myself searching out any others.

For one thing, Chambers (the author) has a totally tin ear when it comes to things Americana. This is the story of a universally disliked TV deejay whose death has been threatened, calling Preston in, His name is Donny Jingle (not his real one, though); the man works for a TV conglomerate called Amalgamated Inter-Coastal Television (or A.I.C.T. for short); and in a town called Monkton City, California. Worse, to my sense of hearing, every time Preston mentions his car by name, he calls it a Chev, but maybe that’s me.

The case turns into murder when one of the go-fer guys working for Donny Jingle dies in a car bombing in his place. Preston digs up a lot of dirt as he investigates, but none of it is very interesting, and the ending is one big yawner.

He doesn’t even make a big play for Donny Jingle’s personal secretary. Meh. This is one mediocre mystery at best.

Wed 2 Jul 2014

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Anyone who’s read Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer novels — by which I mean the early ones, dating from 1947 to 1952, the ones in which Spillane overturned the whole Hammett-Chandler PI tradition by portraying Hammer as a sadistic psycho — has his own idea who should have played the character on screen.

There’s a consensus that the actors cast in the part were inadequate except perhaps for Ralph Meeker in director Robert Aldrich’s subversive version of KISS ME, DEADLY (1955), where Hammer is not the Cold War jihadi Spillane imagined but a cheap punk. It may not be coincidence that Meeker bore a certain physical resemblance to Spillane.

For my money the ideal screen Hammer would need to be a big bruiser, and of the actors from the period who are familiar to me the one I see as most like the character Spillane created was Lawrence Tierney (1919-2002). I challenge anyone to watch Tierney in that fine film noir BORN TO KILL (1947) and tell me he isn’t Hammer to the life. And judging from what I read on the Web, he was also a raging bull in the real world, serving several jail terms for beating people up in bars.

The years of the early Spillane novels coincided with the dawn years of television, but the medium’s antipathy to sex and strong violence seemed to rule out Hammer as a star of the small screen. Then in the late 1950s the character invaded America’s living rooms in the person of Darren McGavin (1922-2006), who went on to star in several other series including RIVERBOAT, THE OUTSIDER and KOLCHAK, THE NIGHT STALKER.

According to an interview McGavin gave decades later (Scarlet Street, Fall 1994), “Universal had made a contract with Spillane, and they made three pilots, one with Brian Keith. They couldn’t show them because they were all too violent.â€

The Keith pilot was written and directed by soon-to-be-superstar Blake Edwards (1922-2010). I’m told on the Web that it’s out there, and someday I’d love to see it. Keith as he looked in the Fifties strikes me as an excellent choice for the part, certainly more so than McGavin, who like Ralph Meeker resembled Spillane more than the Mick’s most famous character.

“I was doing a play in New York,†McGavin recalled, “and they called me to come out and do this series. I read the script…[and] said, ‘This is ridiculous! I mean, you can’t take this shit seriously….[T]his is satire. It’s gotta be satirical.’ [The producers] said, ‘No, no, no—this is really very deadly, straight-on, dead-on serious.’â€

McGavin insisted on playing the part his way, and Universal bigwig Lou Wasserman came down to the set and told him, “You can’t make fun of this material.†McGavin said, “I’m not making fun of it, I’m just treating it in a lighter manner…. We have a contract for me to say the words that are put on the paper. I don’t want anybody telling me how to do it.†What the hell did he think a director was for? Amazingly, McGavin wasn’t fired, and according to him, the episodes “were instantly successful. People thought they were funny.â€

Spillane couldn’t have cared less how the character was portrayed, telling TV Guide “I just took the money and went home.†That magazine’s reviewer declared that HAMMER “could easily be the worst show on TV.†I have yet to find anyone who considered the program a laugh riot but it certainly was successful, running for two seasons of 39 episodes each. All 78 can be accessed on YouTube and are also available on a DVD set.

If the series wasn’t like the Hammer novels and wasn’t a comic parody of Spillane either, how can we describe it? I suggest we think of it as a sort of visual counterpart of Manhunt, the digest-sized crime magazine that debuted in 1953, at the height of Spillane’s popularity, and printed tons of tales by those hardboiled writers who were clients of the Scott Meredith literary agency. I don’t think it was by chance that later in the decade several of those writers got to crank out Hammer scripts, or have their Manhunt stories adapted for the Hammer series, or both.

To take the latter situation first, let’s look at Evan Hunter (1926-2005). By the time Hammer made it to the small screen, Hunter was writing mainstream bestsellers under his official name and the 87th Precinct police procedurals as Ed McBain. Earlier in his career he’d been writing tons of short stories for the hardboiled mags.

It was in Manhunt that readers of the Red Menace era first encountered an edgy alcoholic PI named Matt Cordell. Although originally published as by Evan Hunter, the byline and the protagonist magically changed their names to Curt Cannon when the stories were collected as the paperback original I LIKE ‘EM TOUGH (Gold Medal pb #743, 1958), soon to be accompanied by the novel I’M CANNON—FOR HIRE (Gold Medal pb #814, 1958).

Hunter’s career had skyrocketed so far into the stratosphere that he wasn’t interested in writing for the Hammer TV series, but three of his six Cordell stories from Manhunt were adapted by others into Hammer scripts. Hunter, needless to add, was a Scott Meredith client. So was Henry Kane (1908-1988), who found one of his Manhunt tales about PI Peter Chambers reconfigured as a Hammer exploit.

So was Robert Turner (1915-1980), who devoted a chapter of his memoir SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS ARE WRITERS BUT I WOULDN’T WANT MY DAUGHTER TO MARRY ONE! (Sherbourne Press, 1970) to his experiences working on the Hammer series. As Turner tells it, a whole pile of Scott Meredith clients got flown out to La-La Land and tried their hands at writing for the program but only a few succeeded.

First and by far the most successful was Frank Kane (1912-1968), who was credited with 14 original scripts, 5 more written with a co-author, and 6 Manhunt tales (three of them about his own PI Johnny Liddell) Hammerized either by himself or somebody else. Kane had a habit of using gallows-humor titles for his novels and stories, and both he himself and others tended to use the same type of title for their HAMMER episodes.

Witness the following lists:

KANE NOVEL OR STORY

Bare Trap

Gory Hallelujah!

Lead Ache

Morgue-Star Final

Poisons Unknown

Slay Ride

Slay Upon Delivery

Trigger Mortis

HAMMER SCRIPT BY KANE

Crepe for Suzette

A Detective Tail

A Grave Undertaking

Lead Ache (based on Kane’s short story)

Skinned Deep

Slay Upon Delivery (not based on Kane’s short story)

HAMMER SCRIPT BY SOMEBODY ELSE

Bride and Doom

The High Cost of Dying

Just Around the Coroner

Merchant of Menace

My Fair Deadly

Stocks and Blondes

Swing Low, Sweet Harriet

Robert Turner described Kane as “a big, bluff, hearty guy with a sometimes bawdy but always lively sense of humor… He drove [the producers] crazy, because he steadfastly refused to make carbon copies of his scripts.†He “could turn out a first draft in one or two days. He never gave it to [the producers] right away, though. Not after the first time, when they told him it couldn’t possibly be any good if he’d written it that fast. From then on he just threw the thing in a drawer for two or three days and visited around the lot.â€

He “would come to Hollywood for a month, write four or five scripts, and as soon as the last one was finished and okayed wouldn’t even wait for his check, but would head back to his family in New York….He always took the train….â€

Another well-known crime novelist turning out Hammer exploits was Bill S. Ballinger (1912-1980), who under his B. X. Sanborn byline wrote about a dozen scripts for the series. Most of what didn’t come from East Coast hardboilers was the work of four men who over the years turned out a small army of scripts for Revue Productions’ syndicated TV programs: Fenton Earnshaw, Lawrence Kimble, Barry Shipman and, most prolific of all, Steven Thornley (reportedly a byline of prime-time teleplaywright Ken Pettus).

How about the guys who called the shots? The busiest of the Revue contract directors who worked on HAMMER was Ukraine-born Boris Sagal (1923-1981), who signed 20 of the initial 39 episodes plus 5 from the second season. Sagal soon became one of the top TV directors but his career came to a messy end: while filming the mini-series WORLD WAR III, he walked into the tail rotor blades of a helicopter and was partially decapitated.

Also noteworthy among the first season’s directors was John English (1903-1969), one of the great action specialists who spent much of his creative life helming B Westerns and cliffhanger serials at the legendary Republic Pictures. English moved into television when the new medium displaced theatrical B features and spent several years at Revue.

He directed only five segments of HAMMER but “Peace Bond†boasts perhaps the most exciting climax of any of the 78 episodes. McGavin’s mano a mano with an evil lawyer (Edmon Ryan) represents Republic-style action at its no-prop-left-unsmashed finest, every moment perfectly choreographed and complemented by the background music of Republic veteran Raoul Kraushaar.

English’s best bud at Republic was my own best friend in Hollywood, William Witney (1915-2002), the Spielberg of his generation, a wunderkind who at the start of his career was the youngest director in the business. Between 1937 and 1941 the two co-directed 17 consecutive Republic serials, their visual styles so much alike that they often got into arguments about who had shot what.

In the late Fifties, after Republic folded, Witney wound up at Revue, directing episodes of many of the same series English was working on, including MIKE HAMMER. During its second season Bill helmed 13 segments, far more than anyone else except Boris Sagal.

His HAMMER work benefits from innovations like devising L-shaped sets, with the camera positioned at the right angle of the L so he could have it point east and shoot one scene while the technicians were preparing the north arm of the L for the next sequence, then have it swing around, point north and shoot that scene while the crewmen were tearing down the furnishings from Bill’s first shot and setting up what was needed for his third.

If you watch only one of his 13 HAMMER segments, make it “Wedding Mourning†— the last episode filmed, he told me — in which Hammer for once is portrayed as something very close to the brutal psycho Spillane all unwittingly had created. Mike falls for a woman and is about to get married and change his life when his love is murdered and he runs amok, shooting and beating a swath through New York’s lowlifes. If any of the 78 HAMMER episodes qualifies as telefilm noir, this is it.

In the cast lists of any Fifties series you’re likely to find a number of men and women who were prominent in movies from earlier decades and others who were to become famous on TV in the Sixties or later. Among those once better known who appeared in HAMMER episodes were Neil Hamilton, Allan “Rocky†Lane, Keye Luke, Alan Mowbray, Tom Neal and Anna May Wong. The first three also enjoyed later TV fame, respectively as BATMAN’s Commissioner Gordon, the voice of the titular horse on MR. ED, and KUNG FU’S Master Po.

The actors who weren’t all that well known at the time of their HAMMER roles but made their marks later include Herschel Bernardi, Barrie Chase, Michael Connors, Angie Dickinson, Robert Fuller, Lorne Greene, DeForest Kelley, Dorothy Provine and Robert Vaughn. Anyone who can identify all these folks’ claims to fame either is a telefreak of the first water or has the DVD set.

While cobbling this column together I was presented with a copy of the set and have begun watching the episodes. Some of them I haven’t seen in many years, others — mainly those directed by Bill Witney or Jack English — I taped when the series was broadcast on the Encore Mystery Channel.

Will I make it through all 78? Dunno. Will I find anything interesting enough for another column? No idea. But if McGavin’s later PI series THE OUTSIDER ever comes out on DVD it might be worth exploring.

Sun 17 Nov 2013

THE SECOND GREAT PAPERBACK REVOLUTION:

E-Books and the Second Coming of the Pulps and The Paperbacks

by

David Vineyard

It is common on this blog for myself, and others, to bemoan why so many of the great (and admittedly not so great) writers of the past are not represented in today’s book market. The lament usually goes something like this:

They don’t write them like they used to, and all the great old books are lost, forgotten. You can’t find (choose the name of your choice) in print. The only books out there are dull and badly written in comparison. The new generation doesn’t know what it is missing …

In the immortal words of Seinfeld: ‘Yada yada yada…’

Well, I sorry to deny my fellow curmudgeonly collectors and readers one of our pet hobby horses, but our favorite lament is no longer true, and so untrue that the solution to the problem is not in some dusty musty smelling used bookstore, crowded book fair or busy convention where you have to cram a year’s worth of book hunting and buying into a few cramped hours, but no farther away than a fingers touch away and under $10 in cost.

In the last 24 hours I have recreated some major elements of my lost collection, and the most it has cost me for a single volume has been $4, in many cases less than $1. Understand I’m not just talking about obscure or once famous writers from another age, though I’ve recovered my complete Charlie Chan, Philo Vance, Mr. Moto, Bulldog Drummond, Dr. Thorndyke, Father Brown, Sherlock Holmes, Raffles, and Tarzan collections — all for a grand total of $1.99 (the Tarzan); those have been around almost from the beginning, in public domain.

No, I’m talking about a second paperback and pulp revolution equal to the first, and, like the first, in cheap readily accessible attractive and easily transportable editions. Oh, and I might add so far I haven’t spent a dime for the devices to read them, though I certainly plan to buy an inexpensive Kindle soon. Carrying a thousand books in a device smaller than a trade paperback gives a new meaning to the word ‘pocketbook.’

More importantly, some of these writers haven’t been available at these prices since the 1980‘s.

Who am I talking about?

John D. MacDonald, Dan J. Marlowe, William Campbell Gault, Ross McDonald, Peter Rabe, Wade Miller (the complete Max Thursday for .99 each), Frank Kane, Brett Halliday, Mickey Spillane, Donald Hamilton, Stephen Marlowe, Ed Lacy, Henry Kane: and from the pulps, Nebel, Chandler, Hammett, Paul Cain (for free), Carroll John Daly, Robert Leslie Bellem, not to mention Doc Savage, the Spider, the Avenger, the Black Bat, even Nick Carter, Frank Merriwell, and the Rover Boys …

Almost all those books are under $10, most under $5 and many under $1. Some are even free.

Granted, you don’t have the pleasure of an actual book in your hands, and it takes a bit of time to adjust to reading in this format (arguably the Kindle, Nook, etc are closer to actually reading a book), but many of the complaints I’ve heard lodged against e-books here echo what was said of the pulps and paperbacks as well. E-books will never replace the feel of a book, certainly not a leather bound or quatro buckram edition with its scent and heft, but frankly I had less than 100 such books in my extensive collection and few of them were worth what I paid for them. E-books won’t appreciate in value either, but they are here, available, and no doubt will develop their own following.

To quote James Joyce, I’m not trying to convert you or pervert myself, but I am trying to point out that this is far and away the most important revolution in books since the paperback was born. When I began collecting it took me years to accumulate books by John Buchan, Sapper, Dornford Yates, Louis Joseph Vance, Maurice Leblanc, Talbot Mundy, Edgar Wallace, Rohmer, Van Dine, and others. Now all it takes is a few keystrokes and a WiFi or DSL connection. I could, with a little effort, and under $500 dollars, download my entire collection of over forty years worth close to $100,000, in less than eighteen hours — and that only because of sheer volume.

I don’t ask that you adapt to the e-book, or even read one, but don’t complain about expensive limited reprint editions or the scarcity of this material. Everyday more volumes are being added and new generations of readers are discovering these writers, people, I might add, who would not have purchased them from a paperback kiosk and certainly not in limited overpriced editions. Most of these books have reviews by people who read and enjoyed them and don’t know there ever was a paperback revolution.

I currently reside in a small town, a small and spectacularly illiterate community, where the only source of books are a high school library and the Dollar General, and neither updates its stacks often or carries much more than women’s soft core porn, vampire and ‘romantic suspense’ novels. A treasure is a remaindered Preston and Childs or Cussler. Once a month, if I’m lucky, I get to a Hastings. For now that’s it. But, at my fingertips I have access to books from around the world in countless languages and libraries as important as Oxford’s Boedelian and Harvard.

Like the first paperback revolution this includes an entire new world of original e-books, many better than you could hope, or no worse than what you find on the mass market book stands at Wal-Mart, and numerous sources of free books. I can also, for far less than the near $30 they cost on the stands, purchase the latest bestseller. You can even purchase an e-book “safe†for $20 to protect your collection — more than I can say for actual books.

Then too, those of us who have been married should welcome the end of those long forbearing stares when our collection threatens to over run the house having already driven the cat and both cars out of the garage and threatening to cause the ceiling to collapse by their sheer weight in the attic…

Books and collecting have always evolved. Don’t be the guy complaining because some German named Gutenberg put all those monks copying books out of business. This is not a fad, it’s a revolution, and standing in the way of one has never been a good idea.

How could any of us complain about our favorite writers being in print and finding new and enthusiastic readers? Because digital editions take up no actual physical space (a Kindle can hold 10,000 books and will only get more powerful), and cost virtually nothing to reprint, the possibilities are endless.

Most of us converted without pain from 16 mm to VHS to DVD, to Blu-Ray. This is the same thing, only here when a format goes kaput you don’t have to replace everything you own in Beta, you download a free converter and soon it’s all back. Granted Kindle won’t play on Nook and so on, but you can get a free app to read any format or get a free Calibre converter for extinct formats like Microsoft Readers LIT that take up little space on your PC and require no tech savvy to use.

For those of us born in the shadow of the first paperback revolution this one is even bigger, and likely more fundamental culturally. You don’t have to embrace it, but recognize what it means. Book collecting will never be the same again. This is the most important thing to happen to books since Gutenberg, I have no idea where it is going, but if it keeps my favorites from the past available I say it’s going in the right direction.

Somehow I don’t think Erle Stanley Gardner or Mickey Spillane would be the least bothered by having their work bring in money in another format — I can promise you Alexandre Dumas, the most business savvy author who ever lived (despite losing everything numerous times) wouldn’t mind at all.

Collectors, and I include myself, need to dismount our high horses before we fall off of them.

Oh brave new world that has such formats in it.

Wed 25 Jul 2012

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

Black Lizard’s first mystery anthology included the [Harlan] Ellison Edgar winner, “Soft Monkey.” The Second Black Lizard Anthology of Crime Fiction, edited by Ed Gorman (trade paperback, 1988), is 664 pages long with thirty-eight short stories and a full-length novel, Murder Me for Nickels, by Peter Rabe.

Most of the stories are reprints, but the list of authors reads like a Who’s Who of hardboiled detective fiction for the last thirty-five years, including Avallone, Max Allan Cdllins, Estleman, Gault, Hensley, Lutz, McBain, Pronzini, Spillane, Willeford, et al.

Of the book’s three new stories, I especially liked Jon Breen’s baseball mystery about a streaker (remember them?).

There is also a Hall of Fame quality to The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carroll & Graf, trade paperback, 1988), which in its 592 pages offers stories about almost every important private eye, including Philip Marlowe in “Wrong Pigeon,” the last story Chandler wrote.

Only Hammett (readily available elsewhere) seems to be missing among the authors who include current masters like Hansen, both Collinses (Michael and Max Allan), Lutz, Pronzini, Muller, Estleman, and Grafton. The editors also dug out early work by Carroll John Daly, Robert Leslie Bellem, Fredrick Brown, Gault, McBain, and Prather, as well as rarities: a Paul Pine story by Howard Browne and a private eye story by Ed Hoch, who doesn’t usually write in that genre.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.

Editorial Notes: A complete list of authors for the Black Lizard anthology is as follows: Stories by Michael Avallone, Timothy Banse, Robert Bloch, Lawrence Block, Ray Bradbury, Jon Breen, Max Allan Collins, William R. Cox, John Coyne, Wayne D. Dundee, Harlan Ellison, Loren D. Estleman, Fletcher Flora, Brian Garfield, William C. Gault, Barry Gifford, Joe Gores, Ed Gorman, Joe L. Hensley, Joe R. Lansdale, Richard Laymon, John Lutz, Ed McBain, Steve Mertz, Arthur Moore, Marcia Muller, William F. Nolan, Bill Pronzini, Ray Puechner, Peter Rabe, Robert Randisi, Daniel Ransom, Mickey Spillane, Donald Westlake, Harry Willeford, Will Wyckoff, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro.

Contents for the “Mammoth” collection:

Raymond Chandler, ‘Wrong Pigeon’ [aka ‘The Pencil’] (1971: Philip Marlowe)

Carrol John Daly, ‘Not My Corpse’ (Race Williams)

Robert Leslie Bellem, ‘Diamonds of Death’ (Dan Turner)

Fredric Brown, ‘Before She Kills’ (1961: Ed and Am Hunter)

Howard Browne, ‘So Dark For April’ (1953: Paul Pine)

William Campbell Gault, ‘Stolen Star’ (1957: Joe Puma)

Ross Macdonald, ‘Guilt-Edged Blonde’ (1953: Lew Archer)

Henry Kane, ‘Suicide is Scandalous’ (1947: Peter Chambers)

Richard S. Prather, ‘Dead Giveaway’ (1957: Shell Scott)

Joseph Hansen, ‘Surf’ (1976: Dave Brandsetter)

Michael Collins, ‘A Reason To Die’ (1985: Dan Fortune)

Ed McBain, ‘Death Flight’ (1954: Milt Davis)

Stephen Marlowe, ‘Wanted — Dead and Alive’ (1963: Chester Drum)

Edward D. Hoch, ‘The Other Eye’ (1981: Al Darlan)

Stuart M. Kaminsky, ‘Busted Blossoms’ (1986: Toby Peters)

Lawrence Block, ‘Out of the Window’ (1977: Matt Scudder)

John Lutz, ‘Ride The Lightning’ (1985: Alo Nudger)

Sue Grafton, ‘She Didn’t Come Home’ (1986: Kinsey Millhone)

Edward Gorman, ‘The Reason Why’ (1988: Jack Dwyer)

Stephen Greenleaf, ‘Iris’ (1984: John Marshall Tanner)

Bill Pronzini, ‘Skeleton Rattle Your Mouldy Leg’ (1985: Nameless Detective)

Marcia Muller, ‘The Broken Men’ (1985: Sharon McCone)

Arthur Lyons, ‘Trouble in Paradise’ (1985: Jacob Asch)

Max Allan Collins, ‘The Strawberry Teardrop’ (1984: Nate Heller)

Robert J. Randisi, ‘The Nickel Derby’ (1987: Henry Po)

Loren D. Estleman Greektown’ (1983: Amos Walker)

Sat 3 Mar 2012

Posted by Steve under

Publishers[8] Comments

If you like (love) old vintage crime fiction as much as I do, and if you have a Nook, Kindle or other similar electronic reading device, you’re in luck.

A new ebook website, Prologue Books, has been in the works for the past few months, and it’s now online at www.prologuebooks.com.

You’ll find a complete list of current offerings below. Greg Shepard of Stark House Press, one of the fellows responsible for this new line of books, tells me that other authors yet to come are Harry Whittington, Dan Marlowe, Helen Nielsen, G. H. Otis, Jack Webb, Gil Brewer, Louis Trimble, Barry Malzberg. Westerns are next. Science fiction and adventure are coming, he says. (The other fellow involved is Ben LeRoy, editor of Tyrus Books. Trust me. These guys know what they’re doing.)

My reaction? What a great idea! One whose time has come. The good stuff. The kind of tough, hard-boiled fiction I’ve been reading for over 50 years. Looking through the list of books below, I bought some of them new off the local drugstore’s spinner rack when I was still in my teens. (I still have them.) The others in my collection I had to scrounge up from used bookstores here and there all over the country, from Maine to St. Louis and back again.

And here they are again, all spruced up, the dust brushed off and ready for a new generation of readers. Personally all I could wish for are paper editions as well, but this is the next best thing. Believe me, this is the best news I’ve had all week.

Robert Colby

Run for the Money

The Faster She Runs

The Deadly Desire

The Captain Must Die

Secret of the Second Door

Lament for Julie

Kim

Beautiful But Bad

These Lonely, These Dead

Murder Mistress

The Star Trap

Kill Me a Fortune

In a Vanishing Room

The Quaking Widow

Richard Deming

This Game of Murder

Tweak the Devil’s Nose

Give the Girl a Gun

The Gallows in My Garden

Fletcher Flora

The Seducer

The Brass Bed

Skuldoggery

Park Avenue Tramp

The Hot Shot

Lysistrata

Wake Up With a Stranger

Killing Cousins

Leave Her to Hell

William Campbell Gault

Sweet Wild Wench

The Convertible Hearse

Square in the Middle

Vein of Violence

The Wayward Widow

The Bloody Bokhara

Murder in the Raw

Dead Hero

County Kill

Don’t Cry for Me

The Hundred Dollar Girl

The Canvas Coffin

Run, Killer, Run

Night Lady

Million Dollar Tramp

End of a Call Girl

Death Out of Focus

Day of the Ram

Blood on the Boards

Orrie Hitt

Shabby Street

Woman Hunt

Untamed Lust

Unfaithful Wives

The Sucker

The Promoter

The Lady is a Lush

Suburban Wife

Sin Doll

Sheba

Pushover

Ladies Man

I’ll Call Every Monday

Dolls and Dues

Frank Kane

A Short Bier

A Real Gone Guy

Trigger Mortis

Red Hot Ice

Johnny Liddell’s Morgue

Dead Weight

Stacked Deck

Henry Kane

The Case of the Murdered Madame

Martinis and Murder

Don’t Call Me Madame

Death of a Dastard

Armchair in Hell

Fistful of Death

Death is the Last Lover

M. E. Kerr

Fell Down

Fell Back

Fell

Ed Lacy

The Freeloaders

Two Hot to Handle

Whit Masterson

A Hammer in His Hand

A Shadow in the Wild

Badge of Evil

Dead, She Was Beautiful

Evil Come, Evil Go

The Dark Fantastic

A Cry in the Night

Marijane Meaker

Scott Free

Game of Survival

Wade Miller

Deadly Weapon

Murder Charge

Shoot to Kill

Uneasy Street

Murder – Queen High

Calamity Fair

Vin Packer

The Young and Violent

Girl on the Best Seller List

Something in the Shadows

Dark Don’t Catch Me

Come Destroy Me

Alone at Night

5:45 to Suburbia

Don’t Rely on Gemini

The Damnation of Adam Blessing

The Evil Friendship

The Hare in March

The Thrill Kids

The Twisted Ones

Three Day Terror

Intimate Victims

Kin Platt

Murder in Rosslare

Match Point for Murder

Dead As They Come

The Body Beautiful Murder

The Giant Kill

The Kissing Gourami

The Princess Stakes Murder

The Pushbutton Butterfly

The Screwball King Murder

Talmage Powell

With a Madman Behind Me

Man Killer

Start Screaming Murder

The Girl’s Number Doesn’t Answer

The Killer is Mine

The Smasher

Corpus Delectable

Peter Rabe

The Silent Wall

The Return of Marvin Palaver

The Box

My Lovely Executioner

Murder Me for Nickels

Journey into Terror

Blood on the Desert

Benny Muscles In

Anatomy of a Killer

Agreement to Kill

A Shroud for Jesso

A House in Naples

Charles Runyon

The Anatomy of Violence

Color Him Dead

Kiss the Girls and Make Them Die

The Prettiest Girl I Ever Killed

Thu 8 Sep 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 6: The Black Mask Brotherhood

The chances are that the 1957 to 1961 TV phase of the American Private Eye will be remembered as the most slickest in the TV genre. (“Slick,” as in the sense of smooth and efficient, streamlined.) There had been nothing else like before and nothing since has managed to equal the quintessence of its visual style.

In short, it was a curious phenomenon seemingly belonging to time, by way of inspiration, aided and abetted by style. This unique time period ranges from, say, Richard Diamond, Private Detective (CBS, 1957-59; NBC, 1959-60) to Michael Shayne (NBC, 1960-61). Fortunately, the phase didn’t last long enough to become a parody of itself (unlike the later TV Spy cycle) and remains therefore a largely unblemished sub-genre.

Hollywood films of the 1940s such as the obvious contenders The Maltese Falcon (1941), the 20th Fox “Michael Shayne” films with Lloyd Nolan (1940 to 1942), Murder My Sweet (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946), featuring private detectives, and fashionably now termed as film noir, had as their inspiration the modern literary genre: from early hard-boiled works by Hammett and Carroll John Daly to more contemporary authors such as Jonathan Latimer, Brett Halliday [Davis Dresser] and Chandler. All except Latimer had been contributors to the pulp magazines (Black Mask, Dime Detective, Spicy Mystery, Thrilling Detective, etc.).

This Hollywood studio period embodied the on-screen noir tough guy, epitomized by a Humphrey Bogart or by an unlikely Dick Powell (Cornered, 1945). They were tense and tight-lipped, yet agile. Men of a cynical disbelief that slipped easily into bemused irony. Their film world was often corpse-littered and bafflingly plotted.

The early period of TV Private Eyes (around 1949 to 1954) tended to stem from radio or were under the executive thumb of proprietorial sponsors. One of the earliest series was Martin Kane, Private Eye (NBC, 1949-54), which seemed to change its leading actor with each season. Charlie Wild, Private Detective (CBS, 1950-51; ABC, 1951-52; DuMont, 1952) was an extension of sponsor Wildroot Cream’s The Adventures of Sam Spade, Detective radio series (Howard Duff).

The Cases of Eddie Drake (DuMont, 1952) was followed by The Files of Jeffrey Jones (syndicated 1954-55); Don Haggerty played the featured PI in each. Disappointingly, these on-screen characters and their milieu belonged strictly to 1940s Hollywood.

The TV Private Eye phase of the late 1950s, on the other hand, appeared to be the result of several exciting events. Primarily, the advent of paperback priginals led by Fawcett’s line of Gold Medal books in 1950 (previously, paperback books had been reprints of hard cover editions). Genre authors published by Gold Medal in the 1950s or its companion imprint, Crest, included Richard S. Prather (with the Shell Scott novels), William Campbell Gault (Joe Puma novels), Stephen Marlowe (Chester Drum novels), Curt Cannon [Evan Hunter] (Cannon/Matt Cordell stories).

Additionally, Henry Kane for Avon & Signet Signet & Avon (Peter Chambers), Thomas B. Dewey for Dell (Pete Scofield) and Frank Kane also for Dell (Johnny Liddell). Reprinted from hardcover were Mickey Spillane for Dutton then Signet (Mike Hammer, of course), a publishing phenomenon, and Brett Halliday for Dodd Mead and Dell (Mike Shayne). Hard-boiled private eye stories seemed to be flavor of the month (or should I say, decade?).

Another strong influence appeared to be the increasing sophistication of jazz music and the contemporary jazz musicians’ sartorial inclination toward what was known as the Ivy League Look (think jazz saxophonist Gerry Mulligan or Craig Stevens in the 1958-61 Peter Gunn or even Dick Van Dyke in the 1961-66 sitcom The Dick Van Dyke Show).

Collegiate, soft-shouldered suits with button-down shirts and slim ties. Rather timely, for four albums which are now considered seminal jazz records (Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um and Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come) were all released in 1959.

I remember reading somewhere that the tough-as-nails TV Western hero evolved from his place on the prairie to the mean streets of the TV Private Eye. Interestingly, the Private Eye phase was active during the time of the TV Western stampede (where kiddie actioners like The Lone Ranger and The Gene Autry Show gave way to “adult” Westerns like Cheyenne, Rawhide and Gunsmoke in the mid-1950s).

For me, Scott Brady’s Shotgun Slade (syndicated 1959-61) may have been enjoyable for its account of a gun-toting investigator in the Old West — complete with jazz score! — but I am not at all sure about the theory that Jim Hardie (Tales of Wells Fargo), for instance, might have become someone like Stuart Bailey (77 Sunset Strip).

A listing of relevant TV Private Eye series during this period would include The Investigator (NBC, 1958), Markham (CBS, 1959-60), 21 Beacon Street (NBC, 1959; ABC, 1959-60), Coronado 9 (syndicated 1960-61), Bourbon Street Beat (ABC, 1959-60), Hawaiian Eye (ABC, 1959-63), Philip Marlowe (ABC, 1959-60), Johnny Midnight (syndicated 1960), Surfside 6 (ABC, 1960-62), The Brothers Brannagan (sic) (syndicated 1960-61) and Michael Shayne (NBC, 1960-61).

Some interesting-sounding pilot shows from the decade include “The Girl from Kansas” (1952) with Barry Sullivan as sleuth Nemo Grey (I can’t tell if the would-be series, to be called Nemo Grey, would be about a police or private detective); “Death the Hard Way” (1954) had William Gargan as PI Barry Craig (directed by Blake Edwards); “Mike Hammer” (1954) was an early try-out starring Brian Keith (written and directed by Blake Edwards); “The Bigger They Come” (1955) from A.A. Fair/Erle Stanley Gardner’s first Cool and Lam novel; “Man On a Raft” (1958) had Mark Stevens as Michael Shayne in an early attempt for a series; “The Silent Kill” (1959) was based on author William Campbell Gault’s Brock Callahan p.i. character.

I left my personal favorites until last. The phase included also the bloodthirsty Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer (syndicated 1958-59) with a suitably brutal, street-fighting, crew-cutted Darren McGavin (and yes, the author’s and character’s names together is the full title). The enterprising (answering service/car phone) Richard Diamond, Private Detective (CBS, 1957-59; NBC, 1959-60) with the always-watchable David Janssen (his first series) and an outstanding jazz score by Pete Rugolo.

Perhaps the best of the Warner Brothers TV private eye shows of the time, 77 Sunset Strip (ABC, 1958-64) was the first to offer an agency-based ensemble private detective team as well as a snappy signature tune. Blake Edwards’ Peter Gunn (NBC, 1958-60; ABC, 1960-61) stands as the epitome of late 1950s TV Private Eyes for me, dealing out action and sophistication in equal doses, along with Henry Mancini’s entirely jazz-based score.

The latter presentation went on to influence many other TV shows, most notably Staccato (aka Johnny Staccato; NBC, 1959-60; ABC, 1960), John Cassavetes’ gift to the small-screen as jazz pianist/private eye working out of a small Greenwich Village jazz club, often accompanying house band musicians Barney Kessel, Shelly Manne, Red Norvo and Red Mitchell.

They were all were taut crime dramas which if anything improved as they went on. The writing and direction was efficient, being vigorous and well-staged despite some unavoidable weaknesses in plotting and performance. The 1950s private eyes were indeed masterful but mannered heroes. By contrast, later makers of TV Private Eye series seemed to suffer from that garish and nervous over-sophistication which bedevilled so many producers in the age of color television.

A significant TV phase of the past that was sadly brought to a halt by two unrelated forces — the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the 1960s TV Spy craze — was the TV Gangster period, led by Quinn Martin’s The Untouchables (ABC, 1959-63). It’ll be my next project.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

Part 5.0: Theatre of Crime (US).

Part 5.1: Theatre of Crime (Hours of Suspense Revisited).

Part 5.2: Theatre of Crime (UK)

Wed 3 Aug 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 5.1: Theatre of Crime (Hours of Suspense Revisited)

Following the riches of the 1950s, the anthology series moved into its final period as a stimulating television form. The enormous mass of episodic series featuring regular characters placed the format of the anthology firmly on the back burner.

Both Dow Hour of Great Mysteries (NBC, 1960) and Boris Karloff’s Thriller (NBC, 1960-62) were essentially, and quite effectively, horror-fantasy series, many with strong elements of mystery.

Dow Hour used celebrated classics such as Mary Roberts Rinehart’s “The Bat”, John Willard’s “The Cat and the Canary” and Sheridan Le Fanu’s “The Inn of the Flying Dragon”.

Half of the premier season of Thriller was composed of crime/suspense stories under producer Fletcher Markle, which included tales by Charlotte Armstrong, John D. MacDonald, Cornell Woolrich, Don Tracy and Fredric Brown. Discovering that horror-fantasy worked even better with viewers when they transmitted “The Purple Room” (1960), producers Maxwell Shane and William Frye took over from Markle and concentrated on the macabre. They unleashed scary treats such as Robert Bloch’s “The Cheaters” and “The Hungry Glass”, Robert E. Howard’s “Pigeons from Hell”, and Harold Lawlor’s “The Grim Reaper”. Much to the viewers’ delight.

The opening season of Kraft Mystery Theatre (NBC, 1961-63; not to be confused with the 1958 series) was made up entirely of British cinema second features (B movies) and it was not until the second season (1962-1963) that the series proper began.

The first two episodes of the latter (crime thrillers “In Close Pursuit” and “Death of a Dream”) were directed by Robert Altman. It wasn’t until I happened upon the Mike Doran/Steve exchange in Mystery*File (July 2009) that one episode that had previously puzzled me, called “Shadow of a Man” (1963) starring Broderick Crawford as insurance investigator Barton Keyes and his assistant Jack Kelly as Walter Neff (teleplay credited to Frank Fenton from a story by James Patrick with no mention of James M. Cain or Double Indemnity), was finally laid to rest. Thanks to their information, “Shadow of a Man” proved to be a pilot for a proposed Double Indemnity TV series.

Something of an immediate sister show to the above, Kraft Suspense Theatre (NBC, 1963-65) boasted three interesting contributions: John D. MacDonald’s “The Deep End” (1964) and William P. McGivern’s “A Truce to Terror” (1964) and “Once Upon a Savage Night” (1964) [the latter published as Death on the Turnpike].

Shamley Productions returned with The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (CBS, 1962-65), but now with its crisp little half-hour story format enlarged to an hour. Among the stretched-out storytelling could be found such gems as Woolrich’s “The Black Curtain” (1962), Richard Matheson’s “Ride the Nightmare” (1962), Henry Kane’s “An Out for Oscar” (1963), the latter with teleplay provided by David Goodis, the superbly spooky “Where the Woodbine Twineth” (1965), from a Davis Grubb story, and the genuinely unsettling “An Unlocked Window” (1965), from a story by Ethel Lina White.

Although a mix of drama, comedy, musicals and would-be pilots, Bob Hope Presents The Chrysler Theatre (NBC, 1963-67) did present an altogether intriguing pilot, or rather a series of pilots, featuring Jack Kelly as private eye/secret agent Fredrick Piper. The first attempt was made with “White Snow, Red Ice” (1964), written by Richard Fielder. It was followed by “Double Jeopardy” (1965), co-starring Lauren Bacall, “One Embezzlement and Two Margaritas” (1966), written by Luther Davis, and, finally, “Time of Flight” (1966), written by Richard Matheson (here Kelly’s name changed to “Al Packer”).

Oh, there was also “Guilty or Not Guilty” (1966), a legal drama pilot starring Robert Ryan and co-scripted by Evan Hunter & “Guthrie Lamb” (the latter name belonging to a private eye character created by Evan Hunter [writing as Hunt Collins] for Famous Detective Stories magazine in the early 1950s). Unfortunately, all of the above remained unsold.

During the 1970s, between the TV pleasures of Harry O (ABC, 1974-76) and The Rockford Files (NBC, 1974-80), Joseph Wambaugh’s Police Story (NBC, 1973-78) was the only other series worth keeping an eye on (the author created the anthology for Columbia Pictures Television).

Arguably, one of the finest genre anthologies to grace the small-screen, even though it was nearly 40 years ago, the earthy stories culled from LAPD interviews were developed into some remarkable episodes, among them “Requiem for an Informer”, where a careful rapport develops between a detective and his street-wise informer, “The Wyatt Earp Syndrome”, focusing on Harry Guardino’s obsessive officer, and the two-hour “Confessions of a Lady Cop”, with Karen Black as a vice detective on the edge of a nervous breakdown. The series Police Woman (NBC, 1974-78) evolved from “The Gamble” (1974) and Joe Forrester (NBC, 1975-76) from “The Return of Joe Forrester” (1975).

Fallen Angels (Showtime, 1993; 1995) seemed to be created as something of a small-screen tribute to hard-boiled literature. The carefully constructed series unfolded its noir-ish stories at a leisurely pace, underlining a symbiotic relationship between actor and story.

In this writer’s opinion, all episodes were nothing short of superb. Many remain etched firmly on the memory. For instance, Jonathan Craig’s “The Quiet Room”, in which two corrupt cops receive their just punishment, Jim Thompson’s “The Frightening Frammis”, celebrating flashbacks and femme fatales, and Chandler’s “Red Wind”, featuring an interminably morose Danny Glover as Marlowe.

The above selected anthologies (including the earlier Part 5.0) had, admittedly, minimum influence on the TV Crime and Mystery genre in general, but their exposure of the work of important crime authors (the Chandlers, the Hammetts, the Christies) acknowledges the form as something of a television pinnacle.

The sheer range and diversity of these one-off presentations during the latter half of the last century remain as something to marvel. Perhaps this overview may serve to mark its passing.

The concluding Part of this history of genre anthologies will observe the UK television history.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

Part 5.0: Theatre of Crime (US).

Sat 23 Oct 2010

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

PETER GUNN. Pilot: “The Kill.” NBC-TV, 22 September 1958. Craig Stevens, Lola Albright, Hershel Bernardi, Hope Emerson. Guests: Gavin McLeod, Jack Weston. Written & directed by Blake Edwards. [The series: 1958-1960, NBC; 1960-1961, ABC.]

GUNN. Paramount Pictures, 1967. Craig Stevens, Laura Devon, Ed Asner, Sherry Jackson, Albert Paulson, M.T. Marshall, Helen Traubel, J. Pat O’Malley, Regis Toomey. Screenplay by Blake Edwards & William Peter Blatty. Directed by Blake Edwards.

PETER GUNN. TV-movie/pilot, ABC, 22 September 1958. Peter Strauss, Barbara Williams, Peter Jurasik, Pearl Bailey, Charles Cioffi, Jennifer Edwards. Written & directed by Blake Edwards.

Lt. Jacobi: Pete, I’ll go after you as fast as I go after Fallon (Fusco).

Peter Gunn: Then I have nothing to worry about. (Gunn walks away.)

Lt. Jacobi to Edie: Can’t you do something?

Edie: Sure. What would you like me to sing?

Some ideas are just too good for one telling. Roy Huggins novella “Appointment with Fear,” a Stuart Bailey private eye tale, was the basis for the films The Good Humor Man and “State Secret,” the pilot for 77 Sunset Strip (and at least two episodes), and the pilot for City of Angels. So Blake Edwards, with variations, used “The Kill,” the pilot for Peter Gunn, as the basis for the 1967 feature film and the 1989 refit with Peter Strauss.

The basic story, as outlined in “The Kill,” is that an aging gangster is killed by two assassins dressed as cops in a phony cop car. Peter Gunn owed the old time mobster his life and won’t leave his death alone.

An ambitious gangster (Gavin McLeod — called Fallon here, Fusco in the movie) wants to take over and blows up Mother’s, the jazz bar run by Hope Emerson where Peter Gunn’s chanteuse girlfriend Edie sings, as an example of how his extortion racket will work. Gunn figures it out, puts pressure on Fallon’s top man (Jack Weston) and sets him up as a target for the two phony cops.

It wasn’t as if borrowing was new to Blake Edwards. He began his career creating singing detective Richard Diamond for Dick Powell on radio, then moved into screenplays and television. He updated Richard Diamond as a smooth non-singing private eye played by David Janssen for television, then he also wrote and directed a pilot with Brian Keith for a Mike Hammer series.

Peter Gunn was very much a cross between the cool hip buttoned down and laid back Richard Diamond and the tough violent jazz themed world of Mike Hammer.

Peter Gunn, for the uninitiated, is a private eye in a riverfront town that is never named but always seems a bit wet and foggy. He operates out of Mother’s, a smoky bar where his girl friend Edie is the singer, and he stands at the bar and exchanges hip humor with the owner, Mother. His chief ally on the police force is Lt. Jacobi, a human, dogged, world weary policeman.

Peter is aided by a small army of informers and snitches, all colorful, eccentric, and prone to theatrics. The closest literary equivalent to Peter Gunn was likely Henry Kane’s Peter Chambers who has a similar jazzy offbeat quality — and ironically (or not), Kane wrote the only novelization of the television series.

To add to the cool dialogue, complex plots, and moody noirish look the series was blessed with perhaps the most recognizable theme in television history, Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn theme.

What the Monty Norman/James Bond theme is to spy fiction, the Gunn theme is to crime. It is simply unforgettable (little wonder, in addition to Mancini, at the time his orchestra included legendary John Williams.) Even people who never heard of Peter Gunn know that iconic theme.

One more element came into play: perfect casting. If there was a better choice than Craig Stevens to play Peter Gunn I can’t imagine him. Stevens was a minor B-actor whose biggest role was probably that of a shell shocked soldier in Since You Went Away and by the time of Peter Gunn had fallen to appearing in films like The Preying Mantis and Abbot and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Just before Peter Gunn he had an outstanding role as a cool gun man in Budd Boetticher’s Buchanan Rides Alone, which may well have led to his being cast as Gunn. For whatever reason, he took the part and ran with it. The result was like seeing Mike Hammer played by Cary Grant. It is simply one of the most iconic roles in television history, on a level with Lucy and Raymond Burr’s Perry Mason.

Craig Stevens is Peter Gunn. Much of the character and mood established with nothing more than a raised eyebrow or a his cat like walk. Craig Stevens is Peter Gunn the way Sean Connery was James Bond or Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes.

For American audiences, Peter Gunn and Stevens were the transition from Mike Hammer to James Bond.

The rest of the cast included Lola Albright as the sexy somewhat melancholy Edie who knows her man is only her man in a limited way:

Edie: Is it true what they say about you? Pete, gun for hire?”

Peter: True.

Edie: I’ve saved up. What say I buy you — a steak.

Hershel Bernardi was cast as Lt. Jacobi the world weary cop and veteran Hope Emerson was Mother, an imposing presence even on the small screen. Veteran character actors like J. Pat O’Malley and Regis Toomey were semi regulars as colorful informers.

The series ran only three seasons on NBC and then ABC. When it went off the air it found new life in syndication, and in 1967 Edwards decided to try again as a feature film. Stevens was back, but Lola Albright was replaced by Laura Devon as a rather wan Edie. Ed Asner was good as a tougher version of Jacobi and Helen Traubel played Mother. O’Malley and Toomey again appeared as informers.

The plot was expanded from “The Kill” with some fine variations — at least one borrowed from Mickey Spillane’s Vengeance is Mine. Albert Paulson was “Fusco,” the Fallon character from the pilot, M. T. Marshall had a standout role as Daisy Jane, a madam who ran a floating whorehouse, and Sherry Jackson appeared as a beautiful and mysterious kook who shows up naked in Gunn’s bed.

Gunn (finding Sherry Jackson naked in his bed): Collecting for the Heart Fund?

Sherry Jackson: No.

Gunn: Girl Scouts?

Jackson: No.

Gunn: Community …?

Jackson: That’s the one.

Gunn: I gave at the office.

The world had changed in six years though Gunn hadn’t, and the whole thing is faintly anachronistic, but it is done with such style that hardly matters. It’s a superior effort all around, with at least three outstanding set pieces, including a shoot out in a mirrored bedroom, a confrontation on a racket ball court (taken in part from “The Kill”), and the finale, a bloody brawl that may well be one of the most violent scenes filmed to that time.

Craig Stevens commands the big screen as he did the small one, but the time for Gunn was gone and though it did well, the critics weren’t kind and Gunn disappeared again. Stevens had several other series that ran varying lengths of time — Man of the World, Mr. Broadway, The Invisible Man, did a pilot for a “Thin Man” series, Nick and Nora (notoriously bad), and probably had his last big role in Edward’s S.O.B.

By 1989 Blake Edwards had moved onto bigger things, but he trotted out Peter Gunn yet again with a new actor in the role, Peter Strauss, then still fresh off his star-making role in Rich Man, Poor Man.

Again a gangster has been killed and a gang war threatens. Peter Gunn caught in the middle has to find the killers and stop the bloodshed.

As a private eye film this is not bad, but as Peter Gunn it just isn’t right.

Strauss makes his first appearance in a dinner jacket with a white silk scarf and looks like Michael J. Fox wearing his father’s suit. Edie has almost nothing to do and is largely replaced by a scatterbrained secretary (in the original series Mother’s was Pete’s office) who has far too much screen time. Peter Jurasik plays Jacobi as a petulant and cynical typical cop. Pearl Bailey has little to do as Mother.

Frankly it’s all tired and hackneyed. Not bad, but not Peter Gunn, not by a long sight. Peter Gunn in a turtle neck just didn’t fit somehow. That said, the film has it’s moments, with a nice variation on the shootout from The Big Sleep at the end. One nice touch, Lt. Jacobi acquires a first name — Hershel.

Strauss might have been good as a private eye. Just not Peter Gunn. As made for television private eye films go, this isn’t bad. If you had never seen Craig Stevens and the original you might even have been impressed.

But it’s Diet Coke, not the Real Thing.

The plot varies even more from “The Kill” than Gunn did, but there are enough similarities you won’t have any trouble recognizing where the idea came from. Charles Cioffi is the gangster this time.

In the years since Peter Gunn projects have come and gone. John Woo had one at one point. It would be nice if by some miracle everything came together and we got one more great Peter Gunn, but it seems unlikely. Gunn is very much of its time, an attitude, an actor, and a handful of people he interacted with, and very much one of the best themes ever written, bar none.

Not that we will be, but perhaps, just this once, we should be grateful for what we have.

Fri 10 Sep 2010

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

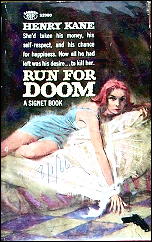

“Run for Doom.” An episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (Season 1, Episode 31). First air date: 17 May 1963. John Gavin, Diana Dors, Scott Brady, Carl Benton Reid, Tom Skerritt. Teleplay: James Bridges, based on the novel Run for Doom (1962) by Henry Kane. Director: Bernard Girard.

Nickie Carole (Diana Dors) is beautiful and talented. She works as a nightclub singer for Bill Floyd (Scott Brady), whose interest in her is intensely personal; sometimes to get her attention he slaps her around a little, but she seems to enjoy it. Floyd takes her for granted, however, and that will prove to be a fatal error.

Yes, Nickie is bad news, but that doesn’t stop naive young medico Don Reed (John Gavin) from wanting to marry her. Even after his father (Carl Benton Reid) tells him the findings of a private eye — that Nickie has already beeen married three times to well-to-do men — Don insists on marrying her.

When his father dies unexpectedly, Don comes into a lot of money; so whenever he waves a diamond sparkler under her nose, Nickie’s big eyes get bigger and Don gets even more attractive.

But the girl can’t help it; Nickie tries to seduce another man just to make Don jealous and because she’s bored with married life. What results from this fracas is a lifetime blackmail plan for Don unless he can figure out how to rid himself of this troublesome wench.

And then Floyd re-enters their lives with his own solution to the Nickie Carole dilemma, this time one that involves more than just slapping her around a little…

Diana Dors (a Brit whose accent is always on the verge of manifesting itself) had a reputation for being merely a sex kitten in the Jayne Mansfield tradition, but here she proves that she can act as well as sing provocatively in a strapless evening gown. There isn’t a false note in her performance; she is the perfect femme fatale — and she gets to perform two song numbers, as well.

In addition to Psycho (1960), John Gavin was a spy in OSS 117 (1968) and had two TV series, Destry (1964) and Convoy (1965). Hitchcock reportedly was unhappy with Gavin’s performance in Psycho, but he more than makes up for it here, traversing the emotional gamut from funny to morose and from naive to sinister.

Henry Kane wrote for TV as well as roughly 30 novels and about as many short stories, many of which featured his series character Peter Chambers. As for other media: Martin Kane, Private Eye (6 episodes, 1951-52), Mike Hammer (1 episode, 1958), Kraft Theatre (2 episodes, 1958), the screenplay for Ed McBain’s Cop Hater (1958), Brenner (1 episode, 1959), Johnny Staccato (1 episode, 1959), and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (2 episodes, 1963).

He even wrote a TV tie-in novel to Peter Gunn (1960), a character some claim may have been “inspired” by Kane’s own Peter Chambers.

You can see “Run for Doom” on Hulu here. For more on Henry Kane and his series character Peter Chambers, read Steve Lewis’s review of Until You Are Dead, earlier here on this blog.