Search Results for 'Raymond Chandler'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 26 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

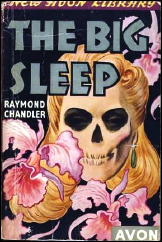

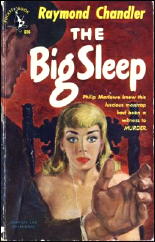

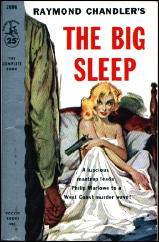

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Big Sleep. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1939. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #7, 1942; New Avon Library 38, 1943; Pocket 696, 1950; Pocket 2696, 4th printing, 1958.

Film: Warner Bros., 1946 (Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall; scw: William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, Jules Furthman; dir: Howard Hawks). Also: United Artists, 1978 (Robert Mitchum, Sarah Miles; scw & dir: Michael Winner).

Speaking of Film Adaptations of Classic Mysteries, Howard Hawks used to reminisce to interviewers about the scene in a book shop in The Big Sleep (Warner Bros., 1946) to the effect of: “I said to Bogart, ‘This scene is awfully ordinary; can’t we do something to liven it up?’ and he put on a pair of glasses and started lisping and camping it up, and it was funny, so I said, ‘Great! Let’s go with that.'”

Which is a good story, except that the passage in Chandler’s novel is written just like that: glasses, obnoxious effeminacy and all. Granted, the scene in Chandler’s book isn’t as funny as the one in Hawks’ movie, but ’tis there and ’twill serve.

The Big Sleep (Knopf, 1939) was another book I read in High School, but I reread it my senior year in College, and I revisit it every ten years or so since then, always finding something fresh and readable to make me glad I came back. The plot is a mess, and the quality of Chandler’s prose is sometimes strained when it should drop like the gentle rain from heaven on the place beneath, but when it works well, there’s nothing like it, and Sleep brings a colorful cast of bit players to pulp-life with energy delightful to behold.

Again, there’s room to carp. Chandler’s handling of gay characters is hysterically unsympathetic (“… I took plenty of the punch. It was meant to be a hard one, but a pansy has no iron in his bones whatever he looks like.”) and describing an over-decorated house, Marlowe says it “…had the stealthy nastiness of a fag party.” Well how would he know?

And again, that’s just carping about a classic. The Big Sleep works on several levels, and offers some happy surprises along the way. I particularly liked the passage cataloguing the detritus of a shabby office building where Marlowe notes, “against a scribbled wall a pouch of ringed rubber had fallen and not been disturbed.”

Nowadays of course, a writer would just say “used condom” and be done with it, but Chandler’s coy self-censorship offers the kind of unique charm that seems lately to have gone the way of all flesh.

Damn. Two references to Shakespeare and one to Samuel Butler in a single review of The Big Sleep; that’s gotta set some record for pretentiousness.

Mon 17 Nov 2008

A REVIEW BY STEPHEN MERTZ:

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Lady in the Lake. Alfred A. Knopf, 1943. Armed Services Edition #838, paperback, 1945. Pocket 389, ppbk, 1946. Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

I was really disappointed upon rereading this one for the first time in fifteen years and found it far from the “masterpiece” which Barzun and Taylor dubbed in it their Catalogue of Crime. According to Frank MacShane’s Life of Raymond Chandler, Chandler was in the dumps when he wrote this, his fourth novel, plagued by personal hassles as well as anxiety over the war in Europe.

It shows. The first half of the book is paced quite nicely and in the first two chapters in particular hero Philip Marlowe is in top wisecracking form. But for the most part the verve and spark of Chandler’s best work are sadly lacking.

By any standards other than Chandler’s own this could pass as a minor but competent private eye novel. But it is Chandler, and here he’s just going through the paces. All of his stock characters and situations are on hand: the brutal cop, the honest but tired cop, the good girl, the mystery girl (two, in fact), Marlowe at constant odds with the law and his own client, being lied to in his search for a missing wife by everyone, every step of the way.

But the writing is peculiarly flat. The plotting, never Chandler’s strong point, is slipshod. The murderer’s identity is glaringly obvious. Marlowe’s solution of the case is unsubstantiated guesswork. The solution itself makes not an iota of sense, raising far more questions than it answers.

But, most irritating of all, a number of very skillfully drawn characters — some quite integral to the story — appear briefly, speak their lines, are talked about for the rest of the book, but never appear on stage again, giving the whole project an uncomfortable, vaguely lopsided effect.

Chandler is my favorite Eye writer, the yardstick by which I measure all others who work the genre, and it hurts like hell to say these things. But it’s hard to believe that The Lady in the Lake is by the same man who gave us such milestone works, such true masterpieces, as Farewell, My Lovely and The Long Goodbye.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1979.

Fri 18 Dec 2009

In the Revised Crime Fiction IV, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Erle Stanley Gardner are denoted as series characters in a series of three novels by author William F. Nolan:

The Black Mask Murders. St. Martin’s, 1994.

The Marble Orchard. St. Martin’s, 1996.

Sharks Never Sleep. St. Martin’s, 1998.

None of the above are given credit as fictional characters in other detective novels. Hammett and Chandler both appeared in Chandler, by William Denbow, for example; and obviously Hammett appeared in Joe Gores’ Hammett.

Question: Are there other novels, ones I’m not thinking of, in which any of the above (including Gardner) appeared as fictional characters?

And as long as I’m asking, what other real life mystery writers may have shown up as characters in novels written by someone else? Josephine Tey, I know, in a couple of novels by Nicola Upson, but since they were published after 2000, they’re beyond the scope of CFIV. Disregarding the date, are there others?

Wed 7 Oct 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

WILLIAM DENBOW – Chandler. Belmont Tower, paperback original, 1977.

A while ago back, Bill Crider said something in his blog about Chandler, by William Denbow. The cover says it’s “…the toughest novel since The Maltese Falcon and Farewell, My Lovely,” but it’s more like a cheap attempt to exploit the success of Joe Gores’ Hammett (1975).

Like any responsible critic, Crider savaged the book, but I remembered buying it at a grocery store when it first came out, and I remembered thinking it wasn’t awful. And that’s all I remembered — I’m afraid I was quite drunk at the time. So I figured I’d try reading it sober and see what it was really like.

Well it just ain’t that bad. It ain’t that good, either, but somehow it didn’t strike me as completely awful.

For starters, I should warn potential readers (both of you) that there’s a lot of flat-footed explication here, some of the characters don’t exactly come to life on the page, and there’s a truly dreadful conversation between the fictional Raymond Chandler and the fictional Dashiell Hammett where Hammett comes up with the name ‘Philip Marlowe,’ and while I was getting through it, I seriously considered ripping my own eyes out rather than reading another line, it’s that bad. So you’ve been warned.

On the other hand, as I say…

Well, the plot moves along quickly, probably because it has to in a hundred-and-fifty-page paperback; the bad guys are engagingly nasty; one or two of the characters do come to life on the page; there’s some good research, and author Denbow occasionally comes up with bits like:

The elevator moved like silk. It seemed to rise on a column of thousand dollar bills.

Hammett opened the door and the reek of stale booze and cigarette smoke hit Chandler like a fist.

“What’s his name?” Chandler.

“Maybe I should just call the cops.”

“Maybe you should do a lot of things. Here’s two more dollars.”

It was a stale smelling little store crammed with newspapers and pulp magazines. The store carried The News, The Jewish Daily Forward; Chandler didn’t see Black Mask, and he figured there was enough real crime people didn’t read crime stories.

I don’t care what anybody says, that’s good writing. There’s also a vivid shot of a stint in a Mexican jail, and an interview with a half-drunk widow just enough like the scene with Jessie Florian in Farewell, My Lovely to evoke it without imitating it.

In all, what you’ve got here is a book that doesn’t merit a lot of praise, and I’m not going to lend it out to my friends, but when I finished reading it, I put it back on my shelf.

Which I guess is something.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA: William Denbow, according to Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, was the pen name of George Stiles. Chandler is his only entry in CFIV under either name. Nothing else is known about Stiles. (He does not appear to be the British composer of such stage and screen musicals as Honk! and Peter Pan, as the latter was born in 1961).

Mon 14 Aug 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

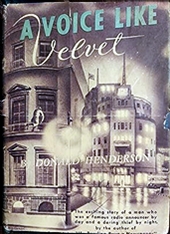

DONALD HENDERSON – A Voice Like Velvet. Random House, US, hardcover, 1946. Previously published in the UK as The Announcer (Hurst, 1944), as by D. H. Landels. The Detective Club [Collins], UK, hardcover/paperback, 2018/2021, with the inclusion of the short story, “The Alarm Bell.” Introduction by Martin Edwards.

Mr. Ernest Bisham kept as still as possible behind the green velvet curtains and listened to the clock ticking, Suddenly he slipped from behind the curtains and made for the door. He went unchallenged along a corridor and opened the first door he came to. Nobody was in it, it was a bedroom. He went to the window and softly opened it. A few minutes later he was hurrying along a side street and panting slightly.

Ernest Bisham is a cat burglar, a second story man, known by Scotland Yard as “the Man in the Mask.†He is not quite Raffles or the Baron, being middle aged, married, and a bit heavier than he was when he was younger. He lives with his wife Marjorie and his sister Bess, and is both highly respected, and a fixture in every home within the broadcasting range of the Broadcasting House (think BBC which Henderson wrote for creating the first soap opera broadcast, Front Line Family, later known as The Robinsons, and the radio play The Trial of Lizzie Borden among others) as the voice of Broadcasting House, Ernest Bisham, the Announcer, newsreader, famed for his closing, “… and this is Ernest Bisham reading it,†in a voice compared to velvet.

For Americans unfamiliar with the UK and the BBC (*) it is hard to comprehend the role the legendary voice of the BBC played in dominating a culture and a way of life, From Buckingham to Whitechapel from the South of England to the Midlands and the North the voice of the BBC was a fixture, a respected and admired figure, the calm assured vaguely upper class sounding voice of a nation, particularly during the War years.

And in Ernest Bisham’s case that voice belongs to a thief.

Without berating the point, the novel quietly puts the reader into the mind and ego of Mr. Bisham but never bores with heavy-handed psychological breast beating. Finding that balance between the melodrama of a thriller (the realm of most gentleman cracksmen) and the dark near Gothic brocade of the serious crime novel Henderson manages to walk a tightrope never making a misstep. Though not as dark as Gerald Kersh’s Prelude to Midnight and Night and the City, Henderson is in the same vein of sharply observed recognizable humans in crisis.

Henderson was an admirer of John Dickson Carr, but he began writing in the shadow of Francis Iles (Anthony Berkeley) and his work is informed by the Iles’ books Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact, two works that freed the British crime novel from the Golden Age mode of the detective story and aristocrats dying in vast manor houses on isolated weekends.

Most writers are lucky to write one classic genre novel over long careers. Some have more, but they are scattered over years of writing and working in the field, and some few like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler have their whole output considered classics.

But it is a rarity to find a writer who only wrote three books, two in the genre of crime fiction, and those two books both classics in the field.

Mr. Bowling Buys a Newspaper was Henderson’s first book, and the better known of the two, the story of a serial killer who only reads the paper after a kill in hope that the police are going to stop him before he kills again. That book was highly praised by critics and writers including Raymond Chandler (who claimed to have read it three times) and Ian Fleming.

A Voice Like Velvet took a more torturous route to its stature as a classic of the crime genre.In fact the book was first published in the UK in 1944 during the War as a mainstream novel as The Announcer, and it was not until its American publication that it was recognized as a classic of the crime genre under the better known American title by Random House.

Driven by the compulsion to spice his life with excitement, Bisham’s chosen manner is cat burglary, he is well aware that he risking everything he has earned, that his marriage, his life, his prestige, are all endangered by his recklessness, and now Chief Inspector Hood has Bisham in his sights and is having him followed, which makes the game even more exciting. As Hood assures him cat to potential mouse:

“I know the public likes to weave its own romance out of things, eh? The life of a detective is supposed to be the most exciting life!†he laughed. “And so is the life of an Announcer, Mrs. Hood assures me of that,†he laughed again. “And so is the life of a cat burglar! Or I suppose! I suppose the public will be very upset if the Man in the Mask is sent to prison. There’s something unromantic about years of penal servitude!â€

While there is suspense and action in the book it is not a thriller. Like Iles, whose work inspired it, the suspense rises from the thoughts and actions of the protagonist, his compulsion, his quick wits, and his inevitable mistakes, but unlike Iles, A Voice Like Velvet would make a delightfully dark Ealing comedy

This was Henderson’s best reviewed novel despite its first small print run. He died at age 41 shortly after it was published in the States under its better known title, and was recently brought back in print in the UK as Velvet by the Detective Club with an attractive jacket, and introduction by genre writer, historian, and editor Martin Edwards, and with “The Alarm Bell†a powerful short by Henderson.

A Voice Like Velvet is well worth your time, a classic of British crime fiction both charming, suspenseful, and ironic.

(*) For anyone interested there is another classic of BBC crime fiction, Death at Broadcasting House (1934) by Val Gielgud and Eric Maschiwitz as Holt Marvell, which was filmed and could recently be seen on YouTube.

Sun 6 Aug 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

ARTURO PEREZ-REVERTE – What We Become. Spanish title: El Tango de la Guardia Vieja. Atria Books, US, hardcover, 2016. Washington Square, US, softcover, 2017.

There was a time when he and his rivals had a shadow existence. And he was the best of them… at least once in his life he was capable of betting everything he had on the table of a casino and traveling home by tram car, cleaned out, whistling “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.â€

There comes a time when I want to settle down with a sweeping romantic novel, mind you not a Romance novel, nor a Gothic novel, nor yet a love story. The Romantic Novel need be none of those things. Instead it is a broader definition of romance, of travel to exotic locations, adventure, of high personal stakes and of human emotions under pressure.

Arturo Perez-Reverte, the bestselling Spanish writer whose novels The Club Dumas (filmed as The Ninth Gate with Johnny Depp), The Seville Connection, and his books about Spanish Renaissance era mercenary soldier Captain Alariste (a two hour film with Viggo Mortenson and a streaming television series) are virtually the definition of a modern Romance novelist, particularly works like The Nautical Chart, The Fencing Master, The Siege, and Queen of the South, which has become a popular international streaming channel hit and remains one of my personal favorite modern novels.

It is almost impossible to read Perez-Reverte and not think of old Warner Brothers films and Bogart or Cary Grant with Ingrid Bergman or Lauren Bacall a lush Max Steiner score and Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet lurking in the background.

With What We Become Perez-Reverte gives us a tale with echoes of Casablanca, Notorious, and To Catch a Thief that spans across multiple decades as two lovers cross paths at different crisis of their lives and that of the world around them.

The lovers are Max Costa and Mercedes (Mecha) Inzunza. Max, a suave thief (eventually Legionaire, deserter, spy, con man, and poseur) is crossing the Atlantic to Buenos Aires on a luxury liner, working his way across dancing with wealthy passengers.

Among those passengers is Mecha, a young bride of a famous composer, Armando de Troeye, who finds herself swept away during a tango by the dashing thief and plunged into a passionate if short love affair in decadent 1928 Buenos Aires. That affair ends as suddenly as it began.

They meet again in 1937 in Nice in the shadow oncoming world war and renew their passion briefly as Max crosses the path of a Spanish spy and again their love affair is cut short.

“I never liked wars. Men like me are usually on the losing side.â€

Finally an aging Max and Mecha meet in Sorrento twenty-nine years after they first met in the shadow of the Cold War where his passion for Mecha, her adult son (who undoubtedly has Max’s smile) there for a chess match with a Russian master, and Max subtly blackmailed by Italian agents, though he is too old for the game.One last theft ties them all together and one last temptation and salvation of sorts.

…all the lies, the doubts and disasters, rooms in boardinghouses and squalid dwellings, fake passports, police stations, prison cells, the humiliations of recent years, loneliness and humiliation, the dim light of endless bleak dawns…

Part Eric Ambler, part Graham Greene, with Perez-Reverte’s uniquely Spanish voice coloring the tale, the book is by turns erotic, kinky, elegant, brutal, violent, suspenseful, and evocative of a Europe that once was of nervous borders crossings, great poverty, and great wealth, moving from the glamour of pleasure palaces to seedy clubs and seedier assignations (Lions at the Kill wasn’t a bad name, but it promised more than it offered.) evoking Harold Robbins or Sidney Sheldon one instant and Alexandre Dumas pere or Raymond Chandler the next without missing a beat.

Arturo Perez-Reverte has yet to disappoint me, whether hinting at something diabolical in the old book trade, uncovering secrets in an ancient church, exploring the international drug trade, swashbuckling through the Inquisition, pitting a fencing master against his deadliest student, investigating a serial killer in the middle of a city under siege, or taking on a Conradian treasure hunt his voice and style are unique, his style evocative of past masters and defiantly unapologetically and gloriously literary, new, and literate.

I can’t promise you, but I don’t think you will ever hear “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo†quite the same way after you meet Max.

Sun 12 Feb 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY TONY BAER:

RAY LORIGA – Tokyo Doesn’t Love Us Anymore. Translated by John King. Grove Press, softcover, 2004. First published in Spain, 1999.

Futuristic tale about a drug company rep who sells pills that erase memories. Long term or short term. Want to get over grief? Erase the memory that the person ever existed. Want to get rid of trauma? Eliminate the traumatic memory. Want to be happy? Take out all the sad.

The book starts with the salesman in Arizona. He’s very good at his work. But he starts to use his own stuff. He has his own tragic memories he can’t handle. And soon he can’t remember anymore.

Each day becomes the same. He cannot remember his parents’ names. Is he married? Is she alive?

He’s transferred to Thailand. But he can’t stop using.

And as the book progresses, the salesman’s memory continues to deteriorate until he can no longer function.

And the narrative itself, fairly straightforward to begin with, starts to become repetitive and confused, as the text and the salesman’s mind deteriorate together.

It’s a similar theme to Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But where the protagonist there decides that keeping a tragic memory of love is still better than nothingness — this book shows what would have happened had the character proceeded with the severance of a memory of a failed relationship that served as a core particle of one’s soul. The soul can no longer hold.

Aside from the story and execution being compelling, the author’s use of simile is as good as anything I’ve read since Raymond Chandler:

‘Days that slip away from me like maggots from inside a shoebox full of holes.’

‘It leaves you like a Christ held up by only one nail.’

‘When she undresses next to me I feel like someone who goes into a ruined church to pray.’

‘I suppose it’s easier for these people, these poor brutes who work as heavies in bars, to headbutt you than not to. Just as it was easier for Hitler to invade Poland than to play the viola.’

‘Happy lines that spread like the milk from a glass that’s been knocked over across an oilcloth table covering.’

‘She says that probably it’s just men who leave their bodies at death, while women remain fastened to theirs like sunken ships at the bottom of a river.’

‘I dress slowly looking at my own clothes with the surprise of someone who attempts to set up a video recorder following the instructions for a washing machine.’

‘Life is a process of acceleration….. Hours for a child are eternal. Hours for a man, on the other hand, fall down from the sky like rain and there’s nothing you can do to stop them.’

It’s a good book. It’s not as revolutionary as the blurbs on the cover insinuate. But it’s good. Don’t kill yourself trying to get ahold of it. But if you like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Philip K. Dick, it’s worth checking out.

Fri 6 May 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY JIM McCAHERY:

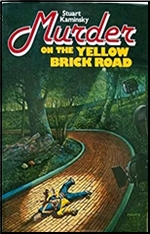

STUART KAMINSKY – Murder on the Yellow Brick Road. Toby Peters #2. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, 1977. Penguin, paperback, 1979.

This is the second in Stuart Kam1nsky’s historical series starring his 1940’s Hollywood private investigator, Toby Peters (a.k.a. Tobias Leo Pevsner), who made his own debut last year in Bullet for a Star. This second entry is far superior to the first. Once again, Hollywood stars join the fun in both major and minor roles.

In this vehicle Toby is summoned from the Warner Brothers lot (where he helped Errol Flynn in Bullet) to M.G.M by an urgent call from Judy Garland, who has just discovered the body of a murdered Munchkin on the still-standing publicity set of Munchkin City from The Wizard of Oz, released more than a year earlier. Peters is hired by Louis B. Mayer himself to keep the investigation quiet and protect Judy, whose own safety seems at stake. Toby’s interview with the “little” suspect arrested in connection with the murder convinces him of his innocence.

Peters, of course, whose wife has already walked out on him and who shares office space with a dentist, is a progeny of the classic Hammett/Chandler tradition:

“My nose is mashed against my dark face from two punches too many. At 44 I’ve a few grey hairs in my short sideburns, and my smile looks 1ike a cynical sneer even when I’m having a good time, but there are a lot around town just as tough and just as cheap. I fit a type, and in my business I was willing to play it up rather than try to cover.”

And again:

“I was doing what private detectives are supposed to do. I was walking the mean streets. I was acting like a damn fool.”

Indeed, Raymond Chandler also has a bit part as himself in the novel. He spots Toby while doing research on flophouses and decides to shadow him, but is waylaid for his efforts. Since Toby is the first real detective he has ever met, our investigator lets him tag along on the case so he can drink in some local color and dialogue first hand.

A second fatal stabbing, a defenestration., and two attempts on Toby’s life all ensue before the climax, in which even Judy has a hand (or an elbow, to be more exact).

Murder on the Yellow Brick Road is a well-paced and very neat yarn, indeed, even if it doesn’t require a wizard to spot the culprit. The dialogue is crisp and lively, especially between Toby and his antagonistic brother, LAPD Lieutenant Philip Pevsner, whose boiling point is nil whenever he runs up against his younger brother.

Add Clark Gable in a minor role as a prospective witness and several other M.G.M. stars in walk-through parts and it all adds up to quite a pleasant stroll down memory lane as well. Unfortunately, there was a very careless printing job by St. Martin’s Press on the first edition which will hopefully be corrected in subsequent printings, including that scheduled for the Mystery Guild.

Kaminsky’s third work is already in progress and will involve Toby Peters with the Marx Brothers.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 1, Number 3 (May 1978).

Sun 13 Mar 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

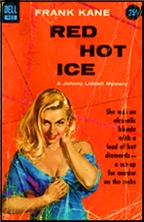

FRANK KANE – Red Hot Ice. Johnny Liddell #9. Ives Washburn, hardcover, 1955. Dell 901, paperback, 1956, Cover by Victor Kalin.

Johnny Liddell is hired by the long-suffering agent of a luscious former star who’s become an uncontrollable lush, and as a result, she now owes $12,000 to the owner of an traveling airborne casino (which is quite an opening gimmick in its own right). To that end she agrees to pay him off using a small fortune in uncut diamonds she’s hidden from the IRS over the years.

When Johnny hires a guy to monitor the transfer, both the guy and the blonde end up dead. The cops think Johnny’s buddy couldn’t resist temptation, and things went bad when he did. Johnny naturally sees things differently, but it’s up to him to prove it.

Kane’s prose is smooth and easy in this one. There are no highs, à la Raymond Chandler — I found no particular lines or longer passages worth quoting, as on occasion I do do – but there are no lows, either. What follows is a lengthy and straightforward murder investigation, in which Frank Kane, the author, is quite good in describing rundown if not out-and-out squalid settings in the city (Manhattan) and environs (New Jersey and Long Island). The latter in fact is where in fact Johnny is at one point taken for a ride – a fairly standard cliché in these kinds of stories, but Kane somehow manages to make it seem fresh again.

Even better is that not only is Red Hot Ice a pretty good PI novel, it is also a detective story, complete with fair play alibis and other clues – well almost. If the New Jersey police had done their job thoroughly, and not just a one-sided one, the case would have been solved all that more quickly – the only semi-sour note I found in this one. Not a classic, in other words, but you can do a lot worse.

Thu 24 Feb 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

HENRY KANE. “Suicide Is Scandalous.†Novelette. Peter Chambers. First appeared in Esquire, June 1948. Collected in Report for a Corpse (Simon & Schuster, 1948). Reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carrol & Graf, 1988).

It’s only my opinion – I have no stats to back this up – but as an author of any number of crime novels, and in particular, the creator of New York City-based PI Peter Chamber, Henry Kane has largely been forgotten in recent years. One exception is, of course, Mike Nevins’ covered his early years in one of the monthly columns he does for this blog. One of the stories covered, in fact, is this very one. Go here.

This is one of the longest excerpts I’ve ever inflicted upon readers of this blog. Bear with me. A little old lady is sitting in Peter Chambers’ office on the other side of his desk. Bear with me. Here goes:

She put the handkerchief away. “The Lieutenant sent us.”

“What Lieutenant?”

“The man downtown. The Detective-lieutenant.”

“Parker?”

“Yes, sir. Lieutenant Parker.”

“A real policeman.”

“A fine, good man.”

“The best.”

“He said this was where to throw it.”

“I beg your pardon.”

“That’s what he said.”

“Throw what?”

“My money. That is, if I insisted on throwing it away.”

“I beg your pardon.”

The smile came back, very tired among the faint wrinkles on her face, and it did something to you, no matter you’re a cynical wiseguy private richard battened down behind a desk over which too much evil has spewed. It got to you, in a corner inside of you, like “Stardust” on strings in a sawdust saloon after a good many brandies. I grunted.

“How much?”

Her eyebrows peaked. “How much?”

“How much do you insist on throwing away?”

“Oh. He said you were expensive. He also said you were a crook.”

“Look, lady– ”

“He was joking, of course. A thousand dollars, perhaps fifteen hundred … ”

“Oh.” Good-bye Stardust, because business is business, and you have got to have the pretzels for your beer. On the other side of the. desk sits your sucker — always; they wouldn’t be on the other side of that desk if they didn’t need you badly. Either you squeeze them, or they squeeze you: you learn that early, Always, on one side of the desk sits a sucker. Could be me.

“Two thousand,” I said.

Now either you find that an extraordinarily fine piece of writing, or you don’t. Kane’s prose, at least in this story, I’d place on the spectrum somewhere between Raymond Chandler and the Dan Turner stories by Robert Leslie Bellem, but closer to Chandler than the out-and-out wackiness of a Dan Turner story:

“Don’t know nothing from absolutely nothing.” He put a wide hand on my chest and he shoved with relish and sharp determination, and the door slapped shut in my face. Mr. Gino Stark got filed away as a handsome young man with a tough-guy complex that needed treatment. Something psychiatric. Like a haymaker.

I took a cab, still rankling along the chest and rumbling around the stomach and trying to engage reasons for administering the treatment for our Gino’s complex, all of which is good for the passage of time, because before I knew it I was paying off the hackie in front of Two Ninety Park.

I pushed my hat back and I looked up at the narrow four sandstone stories of a very svelte little pigmy amongst the flat-faced monsters that go to make up our canyon of Park. No doorman. No nothing. Just a silver-grilled ninon-backed glass door with an ivory boundary and a horse’s head for a phony knocker and a shining lock. I stuck the key in that Williams had given me and I was in a hallway with enough plush for a lupanar, and a curlicue stairway. Very dandy, but a walk-up, nevertheless. Ah, me, and the rasp of a sigh: your detective trudged, grudgingly, bending over to study nameplates. On the second floor front it said BENTLEY.

So, OK. What’s the story about? Chambers’ client, the little old lady from the first except above, does not believe her daughter committed suicide. The police are convinced; that’s why she’s hired Chambers. But besides suicide being scandalous, there is a small matter of a will. The dead girl was rich. Her will leaves half to her mother, half to her sister. If it was murder, and the sister did it, who gets all the money?

Besides being an above average PI story in and of itself, “Suicide Is Scandalous†ends with a lot of detective work going on. There was, in fact, so much detective work going on that I found it confusing. Oh well. You can’t have everything.