Search Results for 'Ross Macdonald'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 3 Aug 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

PHILIP MACDONALD – The Polferry Riddle. First published as The Choice (Collins, UK, hardcover, 1931). Reprinted as The Polferry Mystery (Collins, UK, hardcover, 1932). Reprinted under this title by Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1931. Also: Vintage Books, US, paperback, September 1983.

This one starts out as an ace number one detective puzzler, complete with a dark and stormy night, two visitors to the mansion rescued from the river, then sudden death, with the young wife of the home’s owner found with her throat slashed some time during the night in her bedroom. No weapon can be found.

The three men give each other solid alibis. Each of four others asleep upstairs could have done it, but none of them have a motive. The house was locked tight. An outsider could not have done it. Even Colonel Anthony Gethryn is stumped. With no leads and no evidence the case is put on hold until two of the four members of the household meet with fatal accidents — or are they?

A good chunk of the middle of the story basically becomes a thriller, as Gethryn and his friends from Scotland Yard make a frenzied chase halfway across England to avert the murder of a young woman who was also one of the four.

What each of the “accidents” also does is narrow down the list of possible suspects to the original killing, one at a time, and still the police are stumped. No one could have done it, and with no weapon in the room, it could not have been suicide.

But with Anthony Gethryn on the case, not all is lost, of course. I think the ending is a cheat, though, and I say this reluctantly, since until then, this was a highly readable example of the Golden Age of detective fiction. When it comes down to it, though, I don’t think Gethryn’s logic holds up, nor was I happy when the vital clue was found at nearly the very last moment. Why the police didn’t find it in their original investigation, when they claimed they scoured the house from top to bottom, I have no idea. Put this one solidly in the “Disappointing” category.

Thu 19 Feb 2015

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

Reviewed by Mark D. Nevins:

JOHN D. MacDONALD – Free Fall in Crimson. Harper & Row, hardcover, 1981. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback, 1982. Reprinted many times since.

I’m coming to the end of my run of the McGee series: Freefall in Crimson is the antepenultimate (how often does one get to use that word?), and so I’m somewhat disappointed to say, having just finished it, that it’s probably my second-least-favorite in the series. (My least favorite is Nightmare in Pink: the story seemed contrived and the psychedelic drug references have really not aged well.)

The set-up in Crimson gave no indication that the book would fail to please: the estranged son of a wealthy businessman suspects his father was murdered, and locates problem-solver McGee through some old mutual connections (including a femme fatale from #4, The Quick Red Fox).

Sounds like a typical kickoff for Travis, but the book fails to deliver the goods, at least by the standards JDM set for himself. I have a few thoughts on what’s “wrong” with Crimson:

1. After the emotional intensity of The Green Ripper [reviewed here ], JDM may simply have been set for a let-down. (Green is far from my favorite, but it’s a massive step in a different direction from the series’ trajectory — an exhausting experience for the reader and, I expect, for the author as well.)

2. JDM is a master of storytelling and pacing, and both seemed a bit left-footed here. The chapters and “story chunks” felt disproportionate, and the “mystery” didn’t really hang together: a quick pivot from tracks discovered in the bushes to deep undercover with motorcycle gangs; some amateur porno stuff that seemed like an afterthought and lazy; and a mob scene that advances the plot in a clunky deus-ex-machina way. Even the “economics” didn’t hang together as credibly as they do in so many of the other mysteries–and that’s an area JDM loves.

3. The violence was a bit much — and more egregious than thrilling. Part of that was because it was rushed through (the main baddy Grizzel’s rampage was quick, and much of it “off-screen”), and part was that the bad guy didn’t have the deep intensity of some of the other major psychologically broken bad guys Trav has faced before. (My points 2 and 3 actually cross here–the last 30-40 pages of the book felt like they had been written in a single draft, and not polished up and filled out.)

I also wonder if, and this may be a reach, JDM wasn’t also having a sort of change-of-heart as he wrote this book — hence the strange rough treatment of Meyer at the end. As Travis the protagonist has started to get weary of the world and its changes, has MacDonald the author also grown weary of the mystery/thriller genre? To some extent Green and Crimson seem to criticize the genre itself by the way they yank us out of the comfortable mood we’ve gotten used to getting into, in a comfortable chair with a McGee in our hands. I’ll need to think more about this angle as I make my way through Cinnamon and Silver.

I can’t believe there are only two McGees left. I have sometimes thought it would be great to have someone else take a crack at a new McGee — but it would have to be a very careful choice, and I don’t like Stephen King (who has apparently offered) as a candidate. I’d choose a more “literary” writer, much as the Fleming estate has been doing with the James Bond series. Just like, as I’ve often thought, I’d love to see Garry Disher write a new Stark/Westlake “Parker” novel.

One final problem with Crimson: it’s oddly lacking in the sorts of poetic writing I’ve come to love in a McGee book. There were a few pages I dog-eared, but the passages were short and lacked the usual elaborate internal monologue:

“That is one of the great troubles, I thought, after I hung up. The people you have great empathy with are never conveniently located nearby. Many are, but the rest are scattered far and wide. You see them too seldom. But you can always pick up right where you left off. You know who they are. They know who you are. No reintroductions required.”

and

“Once in a great while, like once every fifty miles, I even got a look at a tiny slice of the Gulf of Mexico, way off to the right. And remembered bringing the Flush down this coast with Gretel aboard. And wished I could cry as easily as a child does.”

(If you’ve read The Green Ripper, that last one should make you choke up a little.)

Tue 27 Jan 2015

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Reviewed by Mark D. Nevins:

JOHN D. MacDONALD – The Green Ripper. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1979. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback, 1981. Reprinted many times since.

I noted in my review of the previous entry in the Travis McGee series, The Empty Copper Sea, that the overall tone of the books seemed to be changing — and with The Green Ripper, the change is really palpable.

To start, this book follows directly from the prior: one lovely lass in danger in Copper actually lived through that book’s climax (“Travis Girls” have even less likelihood of survival than “Bond Girls”), and by the beginning of Green, Travis is starting to think “she’s the one.”

Of course, that doesn’t last long, and the main plot trajectory is McGee going undercover to infiltrate a religious cult that’s up to no good. (I’m avoiding spoilers that you can probably guess.)

Published in 1979, this story feels a lot more current and “real” than the Gold Medal vibe of the first 3/4ths of the series: the story is plausible (and foreshadows events like Waco, Texas); Travis comes alive as a character in his anger and frustrated helplessness; and the overall feeling is much more Nightly News than Drug Store Spinner Rack: it’s like the Polaroid colors of the rest of the series snap into something more like digital focus in Green.

In some ways I miss the nostalgia of the earlier series, but the verisimilitude and violence in this one show MacDonald working at a new level. This is a fine thriller, and would work great as a stand-alone for a new reader; but in the context of the 21-book series (with, I am lamenting, only 3 more to go) The Green Ripper is a real high point as well as a powerful inflection point.

Since one of the things that pleases me most about this series is MacDonald’s “literariness” via McGee’s voice, I’ll again share a passage I dog-eared:

An empty path to walk. It leads toward superstition and paranoia, two whistle stops on the road to incurable depression. Once upon a time I took a random walk across a field. I went hither and yon, ambling along, looking at the sky and the trees, nibbling grass, kicking rocks. The first Jeep to start across that field blew up. So did the people who went to get the people who’d been in the Jeep. And I stood right there, sweaty and safe, trembling inside, while the experts dug over ninety mines out of that field, defused them, stacked them, and took them away. That’s the way it goes sometimes. Philosophy 401, with Professor McGee. Life is a minefield. Think that over and write a paper on it, class.

and

I put the pin in my pocket. Talisman of some kind. Rub the tiny green face with the ball of the thumb. Like a worry stone, to relieve executive tensions. The times I remembered seeing it, she had worn it on the left side, where the slope of the breast began. She had bought it, she said, at a craft shop in San. Francisco at Girardelli Square. I hadn’t been there with her. All the places I hadn’t been with her, I would never be with her. And at those unknown places, at unknown times, there would be less of me present. There can be few things worse than unconsciously saving things up to tell someone you will never see again.

Wed 27 Feb 2013

“SHOOT HIM ON SIGHT!†– William Colt MacDonald. Ace F-389, paperback original; first printing, 1966. Ace ‘Tall Twin’ Western, 2nd printing, 1972; paired with The Troublemaker, by Edwin Booth.

Most westerns, it has been said before, and probably by me, are crime stories. They just happen to take place in the west, and mostly in the late 1800’s. Rustling, bank robberies, feuding between cattlemen and homesteaders and so on, all crime fiction, but unless there’s an element of detective work, Al Hubin does not include it in his bibliography of Crime Fiction, and rightly so. There’s a matter of intent, as well. Most western writers were (and are) writing westerns, and not crime fiction.

And of that aforementioned element of detective work, there is, I have to admit, none in this book. Not that there isn’t a crime, and it’s fairly obvious who the villain is, to the reader that is, and not the narrator of this tale, which is told – and I think this is unusual for westerns, isn’t it? – in first person by John Cardinal, who is on the run from the law.

It seems that to help out his foster parents, he extorted money from a mean, tight-fisted banker and then, knowing that he did wrong, lit out of town. What he doesn’t expect, though, is that his reputation as an outlaw would grow and grow, with WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE posters going up all across the west. Thinking that this is due to sheer laziness on the part of the law – blaming him when the local sheriffs cannot catch up with their own local desperadoes – the noose that John Cardinal has placed around his own neck grows tighter and tighter. He quickly learns to survive in wilder and wilder towns, trying his utmost to live up to his reputation.

Until he reaches the crookedest town of them all, that is, which is to say Onyxton, a town that’s run by Shel Webster, and whose girl friend is a beautiful dance hall hostess named Topaz. And this is where John Cardinal stops and makes a stand, where he finds out who he is, who’s been behind the problems he’s had in life, and what on earth are guns and ammunition doing in boxes labeled sewing machines being sent to small villages just across the border in Mexico?

A number of MacDonald’s other westerns are listed in Hubin, by the way, many of them featuring a rangeland detective named Gregory Quist, and if I have ever read any, it was so long ago that I do not remember. John Cardinal’s forte, on the other hand, seems merely to be being in the right place at the right time, once he’s decided that Topaz is the girl for him, that is.

Here’s a long quote from pages 112-113, a picturesque scene from Webster’s dance hall:

The noise was deafening: the music, the stamping of heavy feet on the dance floor, whirring of the wheel, click of poker chips and everyone talking at once. Cigar and cigarette stubs littered the floor, waves of tobacco smoke drifted through the room. I glanced through the room and finally spied Topaz, seated alone at a corner table. She was dressed about as I’d seen her yesterday, though the dress was of a different pattern, some sort of green and white figured material. Drooped loosely about her shoulders was a white, fringed Spanish shawl. God, she was beautiful, her shining red-gold hair looked as though every hair lay in place. Sleek, was the word for it. Then I thought of Shel Webster, and I scowled. I glanced around, but didn’t see anything of him; probably he was in the adjoining barroom. Not that it made any difference. He couldn’t have stopped me from going to her. I was like one of those big moths attracted to a shining flame.

There’s not a great depth involved here, as you can plainly see, but this is a smoothly told tale that’s not only tasty but a whole lot of fun to read.

— Reprinted from

Durn Tootin’ #5,

July 2004 (slightly revised).

Tue 24 Aug 2010

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

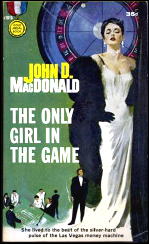

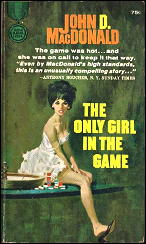

JOHN D. MacDONALD – The Only Girl in the Game. Gold Medal s1015, paperback original; 1st printing, July 1960. First hardcover edition: Robert Hale, UK, 1962. Reprinted many times.

If there was justice in the world, writers would rise each morning and bow three times in the direction of John D. MacDonald’s grave. If that seems a bit extreme, read this description of a typical night in a Las Vegas casino, better still “listen” to it, its cadences and its rhythms:

Casino play was exceptionally heavy. All tables were in operation, and the customers stood two and three deep around the craps and roulette. The murmuring crowd noises blended with the chanting of the casino staff, the continuous roar of the slots, the music from the Afrique Bar and the Little Room, and the muffled burst of applause from the Safari Room where the dinner show was coming to an end. As he worked his way through the throng, Hugh was once again aware at how truly joyless these casino crowds really were.

When play was this heavy there was a special electric tension in the air, but there was something dingy about it. There was laughter, but no mirth. This was the raw sweaty edge where luck and money meet in organized torment. Money is equal to survival. So it is as mirthless as some barbaric arena where slaves are matched against beasts. People in casinos ignore each other. It is a place where each man is intensely and desperately alone.

There is a tendency to discuss MacDonald’s work as if he was yet another suspense novelist, and while he wrote some fine suspense novels, I have always thought of him as first and foremost a novelist. His concerns are those of the mainstream of American literature, and while few writers had his skill or ability at creating suspense, what sets him apart from almost every other writer in the field in that novelist’s eye.

His special skill was not only in creating suspense and character but illuminating the darker byways of the everyday world of business and life. His plots and characters intersect at the place where the day to day world of business breaks down and lines are crossed morally and criminally. No one ever took a more jaundiced or more clear eyed view of the morality — and lack of it — of the average American business enterprise, whether it be a Florida real estate deal gone bad, a con game out of control, or the operation of Vegas casinos.

Vegas and its casinos are the perfect milieu for both MacDonald’s savage moral eye and his very human and sometimes morally fragile characters. Hugh Darren, the hero of this novel, is the assistant manager at the Cameroon’s hotel, one of the big casinos. He is ideally suited to his job, a person with a sharp mind, people skills, and a clear eyed view of the world.

The Cameroon was once the worst run hotel on the strip. Hugh changed all that. But this is a city and a world where success isn’t measured just by results. Sometimes it is measured by whose knife is in your back or at your throat.

Hugh has just run afoul of Max Haines, who runs the casino side of the operation who “knows a lot about how things run around here.” He knows things about their boss Al Marta too, and about secrets the manager of the hotel might not know — or care to know.

Hugh wants to run the hotel at a profit. Max is old school and believes the hotel should lose money to better support the casino, the real source of money. And making sure the margins for the casino stay where they always have been is a job Max does, and boss Al Marta turns his head from, at any cost.

As might be expected, there are two notable examples of MacDonald women in this one. First is Betty Dawson, “a tall brunette with unusually dark blue eyes, and a loveliness of face that was reminiscent of Liz Taylor.” Betty is a singer (“I’ve got no voice and I can’t play much piano …”) who works in one of the hotels rooms and has recently fallen hard for Hugh, the kind of stand up guy she never had in her life before: “We just didn’t have this kind of thing in stock when you first started to trade with us, Betty,” is how she sees it:

Don’t ever love me, Hugh. Just let me love you. I’m ready for hurt. I’m braced for it. You are worth too much to ever fall in love with what I have become.

Betty also acts as a hostess at the hotel. It’s not exactly prostitution — she doesn’t have to sleep with customers — but she does have to lead them on. She knows who and what she is, she doesn’t yet know what it will cost her beyond what it has already cost, her self respect, and something of her heart and her soul.

But for the time being Betty is the happiest she has been in a long long time, and anyone who has ever read John D. MacDonald should know that excess joy is never a good sign.

Sex is one of MacDonald’s great themes, not only the healing power of good sex, but the destructive dangers of the other kind. He sees it both as a blessing and a curse, a redemption and a damnation. His heroes tend to redeem the women in their lives both with sex and with compassion, but it is never cut and dried.

Too much has been made over the redemptive aspect of sex in MacDonald’s books, and not enough perhaps of the awful toll it sometimes takes. Contrary to what some critics like to suggest, a good man is not always enough to save a MacDonald heroine, and even in the McGee books there is a stubborn refusal to allow easy answers.

His heroes are often catalysts in the life of the women in his books, but MacDonald seldom suggests that is enough. It is only one part of healing, one part of life, not everything.

Some critics would do better to actually read MacDonald, rather than simply repeat what they have read about him.

The other MacDonald woman is Vicky Shannard, “… in her thirtieth year, a cuddly dumpling, a pwetty widdle pigeon, a blonde, pink and white, cushiony little cupcake …” who parlayed a history of stripping and living as a professional guest to marriage to Temple Shannard a moneyed older man from New Providence, a golden tongued promoter who operates in the Bahamas and is now in Vegas. But lately their marriage is drifting apart and coming to the Cameroon isn’t going to help.

Vicky is a type MacDonald is never particularly kind to, but he does draw them as they are with due prejudice, but also with an honest eye. She isn’t a monster and Tempe isn’t a victim. They are just people who can’t overcome who and what they are.

At heart John D. MacDonald has the pure American streak of the Calvinist about him. He is attracted to and repelled by the glamour of money and power. Glitter, sin, and easy money bring out the savage in him even as he cannot ignore them or stay away.

All of these people might not create quite so much drama anywhere else, but as Hugh explains to Vicky in a statement that might be the theme of the novel:

“Vicky, dear, when you give people the maximum opportunity to make damn fools of themselves, sexually, financially, and alcoholically, in an environment that makes movie sets look like low-cost housing all sorts of things can happen.”

Finally there is Homer Gallowell of Fort Worth, Texas, a figure that appears in many MacDonald novels in many forms. Homer is a canny old coot, a player and an operator, the sane voice of a man who “had the hard bitten look of a man who had spent the first half of his life sleeping on the ground.”

Gallowell is the kind of individualist who MacDonald always champions over the corporate mind of any business enterprise, smart, tough, straight, and sentimental about only two things — good men and women and good booze.

He’s a fairly common figure in business related novels of the fifties and sixties, the last of a breed before buttondown minds accompanied button-down collars, before the bottom line became the moral standard.

Homer has come to Vegas and the Cameroon to beat the house at its own game.

Homer is an old friend of Betty Dawson too, which is why Max Haines thinks she may be able to play him, because Homer is the one thing Vegas fears more than card counters and con-men — an intelligent gambler with enough money to give them a run for their money, to play their odds, and to win. Max had used Betty for this kind of thing before:

“Now that wasn’t so bad was it?”

“It was as easy as cutting your own throat, Max.”

To give him full credit, MacDonald makes the operations and philosophy of a casino and the machinations of Homer, Max, Al Marta, and Tempe Shannard as suspenseful as any spy novel or bank heist. No one wrote as compellingly about the high pressure world of money and power.

As the strands of the novel tighten into a single skein, the center falls apart as it so often does in MacDonald’s novels. The sham that is Tempe and Vicky’s marriage begins to shatter, Betty’s past begins to catch up with her, and Hugh Darren’s basic morality and honesty is about to come in conflict with Vegas version of the bottom line.

It seemed to Hugh as he sat there that this was a very bad place on the face of the earth, that it was unwise to bring to this place any decent impulse or emotion, because there was a curiously corrosive agent adrift in this bright desert air. Here, attuned to the constant clinking of the silver dollars in forty thousand pockets, honesty became watchful opportunism, friendship became a pry bar, love turned to licence, and legitimate sentiment drowned in a pink sea of sentimentality.

It would not be a good thing to stay in such a place too long, because you might lose the ability to react to any other human being save on the level of estimating how to use them, or how they were going to use you. The impossibility of any more savory relationship was perfectly symbolized by the pink-and-white-and-blue neon crosses shining above the quaint gabled roofs of the twenty-four-hour-a-day marriage chapels.

We are all familiar with MacDonald’s use of color- coded themes, but someone should write a paper on his use of the color pink. He seems to embody all the sins and flaws of the American Dream in the color pink.

The crisis comes when Betty Dawson, her own morality awakened by being asked to play Homer, defies and crosses Max Haines, and through her Hugh Darren faces his own moral and ethical crisis. But when Max and Al push Hugh too far and hit him too hard, he reacts in the true manner of a MacDonald hero and with a little help from Homer …

“What is the one thing in the world most important to these fellers? What do they love the best.”

“Money.”

“And what’s the greatest weapon in the world?”

“Money.”

Hugh and Homer bring down Max Haines and his pals, but at a cost they would neither of them have cared to pay. Some heroines can’t be saved and some dragons are never really slain.

The cabs are bringing the marks in from McCarran Field to fill up the twelve thousand bedrooms. At all the places the gaudy roster of the strip — El Rancho, Sahara, Mozambique, Stardust, Riviera, the D.I. Sands, Flamingo, Tropicana, Dunes, Cameroon, the T-Bird, Hacienda, New Frontier — the pit bosses are watching all the money machines.

Smoke, shadows, colors, sweat, music, the bare shoulders of lovely women, the posturings of the notorious — and that unending, indescribable, chattering roar of tension and money, I shall never see it again, but I will always know it is going on, without pause or mercy, all the days and nights of my life.

The names have changed, the strip is bigger and gaudier than ever, more a playground and fantasy than ever, but MacDonald’s savage critique remains as true and as well observed as before. No one ever looked harder, longer, or more honestly at the phony sentiment, cruel lies, and emotional paucity of big money and big business.

Whether in the standalone novels or the Travis McGee books, whether writing about crime or business that deteriorates into crime, his great theme was an anger and even grief over the soul-numbing results of wounded people in a society with too few second chances.

MacDonald, in the true tradition of the American novel, and not just the hard-boiled school, still echoes Twain’s Huck Finn at the end of his adventures. “I been there before.” That echoes across American literature, that sense of loss and frustration, that realization that life indeed goes on, and we have all “been there before” and will be there again.

Sat 15 Aug 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

THE PRINCESS COMES ACROSS. 1936. Carol Lombard, Fred MacMurray, Douglas Dumbrille, Alison Skipworth, William Frawley, Sig Ruman, Porter Hall, Misha Auer. Screen story: Philip MacDonald, based on the novel The Duchess by Louis Lucien Rogger. (The latter may not exist in book form.) Director: William K. Howard.

Why they insisted on putting Carol Lombard in dramas is one of the great unexplained mysteries of Hollywood. She was born for screwball comedy, and graces some of the highpoints of the genre from Hawks’ Twentieth Century to Wellman’s Nothing Sacred, to the divine Lubitsch’s To Be Or Not To Be.

The Princess Comes Across isn’t quite in that illustrious company, but it’s close. The title alone is worth the price of admission.

Lombard is a would-be actress, Wanda Nash of Brooklyn, who went to Europe and got nowhere. She plans to cash in and hit New York big, though, by pretending to be a mysterious princess, Olga of Sweden, a Garbo-like figure sure to have the press in a frenzy by the time she hits New York.

What she hadn’t counted on was a romantic bandleader in the person of Fred MacMurray as King Mantell, and murder on the ship home. The result is a delightful comedy-mystery that sometimes gets lost among the surfeit of films in that genre from the same era.

Lombard made several films with MacMurray, and allegedly complained she wasn’t getting bigger stars as leading men, but the two are a good team, and if Fred was still a fairly minor leading man at this time, he wasn’t that far off from the films that would propel his career to major star status.

He has an easy-to-take quality that made him ideal for these roles that could have been either dull or strident in lesser hands. MacMurray manages to hit all the right notes, and compliments Lombard as well as bigger name leads like Cary Grant, John Barrymore, or her husband Clark Gable. He was one if the stalwarts of the screwball comedy genre in his own light.

The voyage is a hardly a vacation for anyone. There’s a blackmailer on board targeting Wanda and others, a killer who has taken the identity of one of the other passengers, and to add insult to injury, a convention of international detectives headed for New York.

Poor Wanda couldn’t have picked a worst boat for her trip. Then too she is falling for bandleader MacMurray, the last thing she needs in her life — a musician.

Of course with a mix like that, it’s only a matter of time until a body shows up and sets those nosy professional sleuths to sleuthing, and when their attention turns to Princess Wanda and King Mantell, they have no choice but to turn detective themselves to unveil the real blackmailer and killer.

Dumbrille and Ruman are among the police officers, Inspector Lorel and Steindorf. The set-up reminded me a little of C. Daly King’s novel Obelists at Sea, in which a convention of psychiatrists on a cruise all play detective while New York police Captain Michael Lord keeps his silence and tracks down the killer.

Like all good screwball comedies, the lines flow fast and furious, and the mystery is played for laughs, but with some genuinely spooky moments at night in the inevitable fog as Lombard tries to elude the killer.

Everyone is at the top of their form, and despite all a list of six screenwriters (four credited, two not, including J. B. Priestley), the script holds together extremely well, thanks to Philip MacDonald’s succinct adaptation of Rogger’s novel. (If you ever wondered exactly what the screen story was in relation to the screenplay, this is a good example where a strong story holds together all the disparate contributions of an army of screenwriters.)

We can be fairy certain it is MacDonald who keeps the mystery element in focus, while the comedy spins off of it. That said, I’d love to know what British novelist J. B. Priestley’s contribution was. He was no stranger to mystery and suspense or comedy in books or plays.

The comedy mystery was a specialty of this era: The Thin Man, Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back, The Mad Miss Manton, Arsenic and Old Lace, Whistling in the Dark, Slightly Larcenous, Grand Central Murder to name just a few, and it mixes well with the screwball school.

The high point was likely W. S. Van Dyke’s It’s A Wonderful World and George Marshall’s antic Murder, He Says, but Princess is no slouch, and Lombard and MacMurray are both genuinely attractive and believable.

Somehow this one has been neglected, but it doesn’t deserve that fate. It’s one of the brightest moments of the comedy mystery film at a time when these were being made with all the skills the studio system could bring to bear. The Princess Comes Across, and delivers, a jewel of a comedy mystery.

Sat 23 May 2009

Introduction: The following is an email that David Vineyard sent me following my request for a photo of mystery writer Philip MacDonald. A photo’s since been

found, but I thought the rest of David’s comments were worth sharing.

— Steve

I know a lot of classical detective fans don’t care for MacDonald because he tends toward suspense and even melodrama, but I’ve always thought his best books a sort of antidote to the driest and most formal of the golden age.

I love a good puzzler, but some of the practitioners sometimes forgot that one of the essential parts of the definition of mystery involves some sort of emotional response, not merely intellectual stimulation. Only Freeman ever managed to be dull and interesting, and Dr. Thorndyke is a hard act to follow and most got the dull part right, but not the interesting part.

Thorndyke is unique among fictional detectives in that he came first, and then the real life model, Sir Bernard Spilsbury. Most people don’t realise how much impact Thorndyke had on actual forensic investigation. I don’t know if it still is that way, but the box the forensic kit used to be carried in was always green after Thorndyke’s green forensics kit.

Much of the actual procedure of evidence collection used by the Yard and then by police around the world was taken from Freeman’s descriptions, and the actual forensics box based on his.

I ran across a terrific article in a 1914 issue of the New York Times on their archive site. Seems when Thomas Hanshew, author of the “Cleek, Man of Forty Faces” books (John Dickson Carr was a huge fan), was suspected to have been Bertha M. Clay when he died.

Hanshew, an actor who was one of Ellen Terry’s stock company, and died in England where he was living (and where the Cleek books are set), was a hugely prolific writer who wrote some 150 novels.

Clay, who was Charlotte M. Brame, was a popular writer of books for women (notably young women) whose work was issued in paperbound editions similar to the Nick Carter Nickel Library.

When she died in 1884 Street and Smith were unwilling to give up the golden goose, and apparently Hanshew, John Corryell (Nick Carter), and others took over, sometime writing from her notes, other times probably writing their own books.

The article is particularly kind to both Hanshew and Clay, and not the least snobbish (well, a little when it refers to her young female readers with mint on their breath — waiting in vain, we assume, for that first kiss), and even gives a few examples of how Hanshew changed Clay’s originals to his own style.

The article comes complete with a very nice drawing of Hanshew, who was a handsome fellow. If you have never read the Hanshew books, many of them can be downloaded from Google Books On-Line library, and while they are full of melodrama and over the top writing, you will begin to see what Carr liked about them. I freely admit I sometimes get my fill of the literary and want something bad but fun. Hanshew made the cut in Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek books, and deserves it. He is a true alternative classic.

Hanshew doesn’t play fair as a detective novelist, but Cleek is an interesting character. The heir of a royal throne, he is the finest cracksman in London (The Vanishing Cracksman), but as usual true love turns his hand and he reforms, being hired by Maverick Narkom (great name) Superintendent of Scotland Yard as a consulting detective.

High handed and theatrical (as you might expect from an actor) the books are bad writing at its best. One of the stories seems to me may have been the source for one of Dorothy Sayers Wimsey shorts, the one where Lord Peter finds the sculptor is hiding real bodies in his bronzes.

Impossible crimes and locked rooms are common stuff, but the solutions are often of the poison unknown to science type. The Google edition available of Cleek of Scotland Yard includes the photos from either a silent film or play (I’m not sure which).

Little as either Clay or Hanshew is known now, it seem strange that they should have merited a New York Times article in 1914. Anyway, sometime you might treat yourself to a taste of Cleek, his true love Alicia, his servant Dollops, Mr. Maverick Narkom, and Margot, Queen of the Apaches (French Apaches, not American ones). Readers once read this breathlessly, and truth be told even today they can take your breath away, though not perhaps as they intended to.

Fri 1 May 2009

I’ve received this inquiry in this afternoon’s email. I’m sure I’ve seen a photo of Philip MacDonald on one of his book jackets, but so far I haven’t come across it. I found this one on the Internet, but this is the one that Charles already has. Anyone else?

My name is Charles Seper, and I’m currently working on a film documentary of Philip MacDonald’s author grandfather — George MacDonald. I intend to make mention of Philip in the movie also.

My problem is finding a good photograph of him. The only one I’ve managed to procure thus far is very small and of poor quality. Do you by any chance know of any?

Philip was often asked to speak at various Hollywood functions, so I know there must be a good photo of him somewhere. I also know he wrote many books that I haven’t yet read, so I thought perhaps you might have one which has a picture of the author on the cover.

If you have any idea where I might find a photo I would much appreciate it.

Sincerely,

Charles Seper

Thu 9 Aug 2007

On July 14th I received an email from Al Hubin, author of Crime Fiction IV, about a new discovery that he had made:

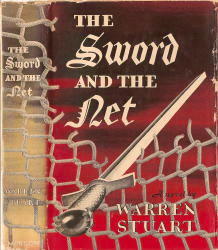

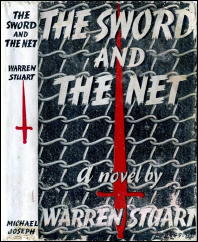

“FYI…to my considerable surprise, I found in Philip MacDonald’s CA [Contemporary Authors] entry the listing of The Sword and the Net as by Warren Stuart. I don’t think anyone’s made this observation before…”

Here’s the Warren Stuart entry as it is (or was) in CFIV:

STUART, WARREN

* The Sword and the Net (Morrow, 1941, hc) Joseph, 1942.

There’s nothing remarkable about the entry. There are many, many authors with only a single title included in CFIV, about whom nothing is known, neither the author nor the book.

Al, of course, did the sensible thing. He ordered a copy of the book immediately. As soon as he received it, he read through it and send me a copy of the dust jacket cover and the blurbs that describe the book on the inside flaps of the dust jacket:

Very occasionally a publisher presents a novel with a story so packed with exciting action and dramatic suspense that he hesitates to reveal any significant part of the plot for fear of spoiling the enjoyment of the reader.

The Sword and the Net

By WARREN STUART

is just that kind of book – so thrilling and unexpected that we are deliberately withholding all description beyond the bare essentials.

THE TIME of the story is 1940-41.

THE PLACE – Berlin and Sweden briefly, then New York and California

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS:

OTTO FALKEN: Aristocratic young German, war ace and hero …

CAROLYN VAN TELLER: The rich, beautiful widow of a New York banker …

[continued on back flap]

RUDOLPH ALTINGER: Ostensibly successful head of a large construction firm in San Francisco …

GUNNAR BJORNSTROM: A withered, kindly, cheerful old gentleman originally from Sweden …

WALDEMAR INGOLLS: A German officer in the last war, but for years resident of California and an American citizen in the highest sense of the word …

CLARE, his daughter: A courageous, lovely girl as bitterly anti-Nazi as her father …

Other Characters: Nazi officials and officers, Swedish peasants, secret agents; seamen; Americans of every type; Nazi saboteurs and spies.

A spy story? Well, perhaps; but much more than that, for the author has blended a subtle development of character and the poignant love story of two people into a tale so packed with action that the pages almost turn themselves.

Before getting to Al’s first-glance opinion of the book, I’ll point out the story also appeared in Two Complete Detective Books, Number 15 (Fall, 1942). The lead novel in that issue was Death Turns the Table, by John Dickson Carr, and of course I have a cover image to show you, one found on eBay at some time in the past.

Here’s Al’s initial reaction: “The story is quite unlike anything I recall of MacDonald’s work … slow moving, interesting but not compelling or fully persuasive. If MacDonald actually wrote it (and we have no other candidates), I’m certainly not surprised it was published under a pseudonym — and one which, so far as I know, was not publicly acknowledged during his lifetime.”

Truthfully, though, Al and I have been scooped on this rather unexpected find. In the latest issue of CADS, #52, which arrived just days ago, is a short announcement of the discovery by Tony Medawar, and more, a short synopsis and review of the book by that noted scholar of mystery fiction himself.

Since I can do no more than a few excerpts from his comments, a few excerpts are all you are going to get. Otto Falken, the hero (or rather anti-hero) whose actions the book follows, is selected by Hitler for a secret mission. Eventually he is required to assist a team of saboteurs in this country. From here, I quote:

“… a thriller rather than a detective story, and something of a Hitchcockian thriller at that. […] It is possible that the plot was first conceived for the cinema.

“… the story […] is not unpredictable but […] is compelling and the novel builds to an exciting climax in the hills outside San Francisco. A fascinating addition to the canon of a fascinating writer and well worth the search.”

As the news becomes more widely disseminated, the search is going to be much harder. A word to the wise may already be too late.

PostScript: Tony also mentions in a footnote to his review something else I didn’t know. As “W. J. Stuart,” MacDonald did the novelization of the 1950s science fiction novel, Forbidden Planet (Farrar Straus & Cudahy, hc, 1956; Bantam A1443, pb, 1956).

Also please note: The link to information for CADS is for issue #51,but #52 can be ordered from Geoff Bradley at the same address, but the price has gone up from $11 to $12. Tell him I sent you.

[UPDATE.] 07-28-09. British bookseller Jamie Sturgeon has come across a copy of the first UK edition (Michael Joseph, 1942), and he’s sent me a scan of the dust jacket. He also adds: “Interestingly apart from a ‘puff’ from James Hilton there’s no other blurb or anything else about the plot/author anywhere.”

Thu 13 Jun 2024

JACK WILLIAMSON – Bright New Universe. Ace G-641, paperback original, 1967. Cover art by John Schoenherr. Collected in Seventy-Five: The Diamond Anniversary of a Science Fiction Pioneer (Hafner Press, hardcover, 2004).

Idealism is confronted with reality, as Adam Cave meets opposition, then disappointment, as he rejects the material comfort which could be his on Earth. The Moon is the site of Project Lifeline, aimed at sending signals to space, seeking other life in the universe. He does not know contact has been made, with his own father, believed dead, and organized opposition has already been created,

His conflict is with those who feel change is always destructive, and indeed with white racists who know their values cannot withstand the shock if the alien culture as it overwhelms Earth’s. The symbol of his triumph is a small Negro boy who now has the power of a transgalactic civilization at his fingertips.

There is a message here, and it is obvious. […] The characters are symbols and little more. It comes as a shock to realize how crude the writing style is, as compared to a craftsman such as [for example] mystery writer Ross Macdonald. There are the ideas, though. Williamson meant for better things, but [this time around], he doesn’t succeed.

— July 1968.