Search Results for 'redhead'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 21 Mar 2020

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

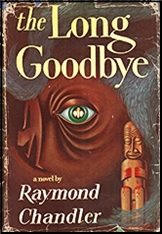

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Long Goodbye. Philip Marlowe #6. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1954. Pocket #1044, paperback, 1955. Reprinted many time, both in paperback and hardcover. TV adaptation: “The Long Goodbye” on Climax, 07 Oct 1954. with Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe. Film: United Artists, 1973, with Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe.

The title of this novel is apt. It is a long book and a complex one, and its detractors say they wish Chandler had said goodbye two-thirds of the way through. What these critics fail to understand is that the novel is one of the most realistic looks into the day-to-day life of a private investigator, and the central plot element, that of Philip Marlowe’s friendship for the mostly undeserving Terry Lennox, is a compelling unifying element. In it we also see a different side of Marlowe than in Chandler’s other novels: the man who is as honorable in his personal relationships as he is in his professional ones.

The story begins when Marlowe first sees Terry Lennox, dissolute man-about-town: he is “drunk in a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith outside the terrace of the Dancers,†a ritzy L.A. nightspot, with a redheaded girl beside him whose blue mink “almost made the Rolls Royce look like just another automobile.” The girl leaves Terry, Good Samaritan Marlowe takes over, and a friendship begins.

It is a friendship that Marlowe himself questions, but it persists nonetheless. Marlowe tells Lennox he has a feeling Terry will end up in worse trouble than Marlowe will be able to extricate him from. and in due course this proves true. The redhead, Terry’s ex-wife, whom he admittedly married for her money, is murdered in the guesthouse at their Encino spread and the trouble that Marlowe sensed begins.

Lennox runs to Mexico, and it is reported that he made a written confession and shot himself in his hotel room. But something feels wrong: The Lennox case is being hushed up, and Marlowe begins to wonder if his friend really did kill his ex-wife. A letter that arrives with a “portrait of Madison” – a $5000 bill that Terry had once promised Marlowe – convinces him his suspicions are justified.

He tells himself it is over and done with, but he isn’t able to forget. The matter plagues him while he is working a case involving an alcoholic writer of best sellers in wealthy Idle Valley (where, he says, “I belonged … like a pearl onion on a banana split”). It begins to plague him even more when Sylvia Lennox’s sister, Linda Loring, appears and plants additional suspicions in his mind. The suspicions spur him onward, and finally his current case and the Lennox case come together in a shattering climax.

At the end Chandler neatly ties off all the strands of this complicated story, and provides more than a few surprises. An excellent novel with a moving ending.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 28 Feb 2020

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

RAYMOND CHANDLER – Farewell My Lovely. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1940. Pocket Book #212, paperback, 1943. Reprinted many times.

Many critics consider The Long Goodbye to be Chandler’s finest novel. This one disagrees. That distinction should probably go to Farewell, My Lovely – a more tightly plotted, less self-indulgent and overblown book, with characters, scenes, and prose of such artistry that it ranks as not only a cornerstone private-eye novel but a cornerstone work in the genre. Its near-flawless construction is all the more awesome when you consider that like The Big Sleep, it is a product of “canniballzation”: It makes extensive use of “The Man Who Liked Dogs” (Black Mask, March 1936); “Try the Girl” (Black Mask, January 1937); and “Mandarin’s Jade” (Dime Detective, November 1937).

Marlowe’s client in this case is Moose Malloy, a giant ex-con with a one-track mind: All that matters to him is finding his former girlfriend, Velma, a redhead “cute as lace pants,” who disappeared after he was sent to prison. Marlowe is a reluctant detective, his first encounter with Malloy having ended in the wreckage of a bar, Florian’s, where Velma once worked and a black bouncer suffering a broken neck; but Malloy won’t take no for an answer.

As Marlowe’s search for Velma develops, “the atmosphere becomes increasingly malevolent and charged with evil.” Among the characters he meets are a foppish blackmailer named Lindsay Marriott; a gin-drinking old lady with secrets and a fine new radio; a beautiful blonde with no morals and a rich husband who doesn’t give a damn; a Hollywood Indian named Second Planting who has “the shoulders of a blacksmith and the … legs of a chimpanzee”; a phony psychic, Jules Amthor: Dr. Sonderborg, who runs a private psychiatric clinic staffed with thugs; Laird Brunelle, the tough operator of a gambling ship called the Royal Crown; and L.A. and Bay City cops, some of whom are as crooked as a dog’s hind leg.

The climax, in which Marlowe and Moose Malloy both come face-to-face with the elusive Velma, is a stunner. Like a number of other scenes — especially Marlowe’s drugged imprisonment in Sonderberg’s clinic, in a room “full of smoke [that] hung straight up in the air, in thin lines, straight up and down like a curtain of small clear beads”-it remains sharp in one’s memory long after reading.

Farewell. My Lovely was filmed twice, once in 1944 as Murder, My Sweet, With Dick Powell as Marlowe, and once in 1975 under its original title, with Robert Mitchum in the starring role. The Powell version is the better of the two, even though Mitchum, aging and slightly seedy, better captures the essence of Marlowe. (Powell isn’t bad, though-a surprisingly gritty performance for an actor who began his career as a crooner in Busby Berkley musicals.) Mike Mazurki’s portrayal of Moose Malloy in Murder My Sweet is more memorable (and credible) than Jack O’Halloran’ s in Farewell. And the noir style of the earlier film better captures the flavor of Chandler’s work than the arty, full-color remake.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 6 Aug 2019

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER -The Case of the Stuttering Bishop. Perry Mason. William Morrow, hardcover, 1936. Pocket #201, paperback, January 1943. Reprinted many more times. Film: First National / Warner Brothers, 1937 (Donald Woods, Ann Dvorak, Joseph Crehan). TV adaptation: Season 2 Episode 20 of Perry Mason ( 14 March 1959.

This isn’t a review. I never finished the book. I got only so far and I stopped. Thinking I might try again where I let off, I realized that I didn’t really remember what was going on, so I stated skimmed through from the beginning, and taking notes as I went. Herewith, the players, with appropriate page numbers:

1. Perry Mason — the kind of attorney you’d want fighting for your interests if you ever get into a legal jam, except if you’re a rich father with an wastrel son, in which case he’ll turn you down flat, no matter much fee he could charge.

1. Bishop William Mallory — a visitor from Australia who comes to Mason as a client, wishing to know about the statute of limitations in a manslaughter case; the problem is, he stutters — is he a real bishop?

5. Della Street — Mason’s highly trusted personal secretary; they go out together for the occasional meal and dancing, but any closer on a personal basis, they never get.

7. Paul Drake — head of a private detective agency with seemingly unlimited manpower at his beck and call; Mason hires him to check out the bishop as well as any manslaughter cases still open from 22 years before.

10. a cab driver — the one who brought the bishop to Mason’s building; he was asked to wait, but the bishop seems to have gone out a back way without paying the fare.

11. Jackson — Mason’s law clerk, a quite capable individual, but a non-factor in this story.

12. Jim Pauley — house detective at the hotel where the bishop is checked in; he has a sharp eye: he noticed someone following the bishop when he went out, and a redheaded dame who was waiting for him when he returned; when she leaves, he goes up to the bishop’s room and discovers a fight has taken place in the bishop’s room and the bishop concussed (and sent to the hospital).

17. Charlie Downes — one of Drake’s operatives who was following the bishop, then the redhead.

19. Janice Seaton — the aforementioned redhead; she claims she’s a trained nurse who answered an ad placed in a newspaper by the bishop; she found the bishop injured, treated him and left him in bed.

27. Renwold C.Brownley, Oscar Brownley (son), and Julia Branner, who married Oscar 22 years before [as reported by Paul Drake] — but while the latter was driving their car after getting married, she hit and killed a man; hence the (trumped up) manslaughter charges. Oscar is now dead, but the girl thought to be his daughter is living with Renwold; the girl’s mother is still a fugitive from justice.

32. Philip Brownley — [as Perry tells Della] a grandson of Renwold also living with him.

33. Janice Alma Brownley — [as Della tells Perry] Renwold’s granddaughter, who was on the same ship as the bishop as he traveled from Australia to the US; did the bishop suspect she was an imposter?

44. Julia Branner — in person, in Mason’s office; on the advice of the bishop, she is hoping to hire him as her attorney. The bishop has told her that the girl claiming to be her daughter (and Renwold’s granddaughter) is a fraud.

From here, it gets complicated. When Renwold Brownley is supposedly shot and killed, no body can be found, in spite of eyewitnesses to the shooting. And what’s worse, the story that Mason’s client tells gets sounds fishier and fishier.

Tue 12 Feb 2019

Posted by Steve under

Magazines[18] Comments

THE TORTURED HISTORY OF MANHUNT

by Jeff Vorzimmer

The first issue of Manhunt appeared on newsstands in late 1952 and within two years became the widely acknowledged successor to Black Mask, which had ceased publication the year before. The stories in Manhunt captured the noir of Cold War angst like no other fiction magazine of its time and paved the way for television anthology shows such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

Manhunt can best be described as a joint venture between publisher Archer St. John and literary agent Scott Meredith, both based in New York. In 1952, St. John published comic books and had recently ventured into and, in fact, developed 3D comics and graphic novels. His company, St. John Publishing, produced what is considered the first graphic novel, It Rhymes with Lust, in 1950, which was part crime, part romance, and followed that up later the same year with The Case of the Winking Buddha. Neither book sold very well and the line, dubbed “Pictures Novels,†was discontinued after the second title.

Archer St. John, always an admirer of Black Mask magazine, the premier pulp magazine from the 1920s through the 40s, felt that since that magazine’s demise there was a void in the world of crime-fiction magazines and an opportunity. Of course, comic book publishers don’t usually have big editorial staffs nor do they solicit manuscript submissions. For that, St. John approached Scott Meredith, a literary agent who was beginning to turn the publishing world on its ear with practices such as charging would-be writers reading fees and submitting manuscripts to publishers simultaneously, creating an auction system of competing bids.

For Scott Meredith it was an opportunity to get his stable of writers in print and create another stream of income. St. John served as the front man to avoid any ethical questions or conflict of interest charges that Meredith might otherwise face. St. John would manage the production of the magazine from layout and illustration to the printing and distribution of the magazine while Meredith’s office would supply a steady supply of fiction and editing.

Of course, it was not a very well-kept secret within the publishing business. Those in the business, with even a passing familiarity with the roster of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, would notice a preponderance of his clients on the pages of Manhunt. In fact, all ten of the most prolific contributors to the magazine were Meredith authors who, between them, contributed over one-fifth of all stories that appeared in Manhunt over the course of its fourteen-year run.

Manhunt has often been referred to, then and now, as a closed shop, only available to the Meredith stable of authors, but that’s not entirely true. As often as not, writers not represented by an agent would submit stories directly to Manhunt. These were forwarded to the Meredith office and occasionally published in the magazine, though the authors were not usually signed to a publishing contract on the strength of a single story.

This would sometimes create awkward moments when a producer from a television studio such as Revue, producers of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and M Squad, would call up the agency looking to secure the rights to a story they read in Manhunt. The Meredith agent would stall the producer, scramble to locate and sign the author, then make the deal.

Archer St. John originally wanted to call the magazine Mickey Spillane’s Mystery Magazine to compete with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, albeit with grittier, more hard-boiled stories. Having Spillane’s name on the masthead would have been appealing to both St. John and Meredith in that, by 1952, Spillane’s first six books had combined sales of 20 million copies. His first book, I, The Jury had sold 3.5 million copies by 1953, when it was adapted for the screen.

When Scott Meredith checked Spillane’s contract with his publisher, Dutton, he found a clause that gave the publisher total control of Mickey Spillane’s name in conjunction with any books or periodicals. If they were to use Spillane’s name on the magazine they had to get Dutton’s permission. However, Dutton balked at the idea.

Dutton felt that short stories were a distraction for Spillane, and they wanted him to get back to the business of writing novels. At that point, it had been over a year since Spillane had delivered his last novel to them (and it would be ten years before he delivered his next one). The name of the magazine was changed to Manhunt, a named borrowed from a then-defunct crime comic book.

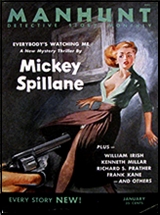

St. John intended to kick off the magazine with a Mickey Spillane story. He had heard that Collier’s Magazine had turned down a novella Spillane had written, “Everybody’s Watching Me,†and offered to serialize the novella in the first four issues of the new magazine and pay Spillane $25,000 (equivalent to $237,000 today). If Spillane’s name could not be on the masthead, it would at least be on the cover of the first four issues.

The print run of the first issue, dated January 1953, was 600,000 copies and sold out in five days. It was digest size (5½”x7½”), 144 pages and priced at 35¢ and $4 for a year’s subscription. In addition to the lead story by Spillane, the issue also included stories by Cornell Woolrich under the name of William Irish; Ross Macdonald, under his real name, Kenneth Millar; and Evan Hunter, later known by the pen name Ed McBain.

It also included a story featuring Richard Prather’s detective Shell Scott, featured in six novels of his own over the previous three years, and, who rivaled Spillane’s Mike Hammer in popularity, and another featuring Frank Kane’s Johnny Liddell. Stories by Floyd Mahannah, Charles Beckman, Jr. and Sam Cobb (Stanley L. Colbert) rounded out the issue.

St. John had his favorite artist, Matt Baker, a black man in the predominantly white world of comic book illustration, do the artwork for Manhunt. Baker was the artist who had done the panels for the first of the two graphic novels St. John had published, but brought an entirely new look to the Manhunt illustrations, heavy ink and each highlighted with a different spot color. Each story had one illustration on the first page in a style not unlike Manhunt.

Pages from the February 1953 issue of Manhunt with illustrations by Matt Baker

Baker himself would do most of the illustrations for the first nine issues, thereby setting the style used for the entire 15-year run. Up-and-coming young artists such as Robert McGinnis, Walter Popp and Robert Maguire, as well as older, more established artists, such as Frank Uppwall and Willard Downes, painted the covers.

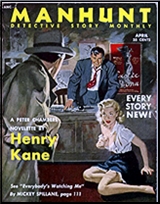

The editorial note on the contents page of the second issue stated that the press run of the first issue probably should have been closer to a million copies. St. John apparently split the difference and ran 800,000 copies of the second issue. In addition to the second installment of “Everybody’s Watching Me,†the lead story was another by Kenneth Millar, a Lew Archer story titled “The Imaginary Blonde†under his new pseudonym John Ross Macdonald.

There were also two more stories by Evan Hunter under the pseudonyms Richard Marsten and Hunt Collins, a Paul Pine story by John Evans, as well as stories by Jonathan Craig (Frank E. Smith), Fletcher Flora, Richard Deming, Eleazar Lipsky and Michael Fessier.

In addition to the contributors of the first two issues, the third issue was notable in that it included stories by older, more established writers such as Leslie Charteris with a Saint story, Craig Rice (Georgiana Craig) with a John J. Malone story, as well as stories by William Lindsay Gresham and Bruno Fischer.

The third issue also contained another two stories by Evan Hunter, one under the pseudonym Richard Marsten. In fact, Evan Hunter contributed 16 stories to the first 9 issues of Manhunt under his own name and various pseudonyms and 48 stories over the entire life of the magazine, making him the most prolific contributor by far. For a magazine that was supposed to be all about Mickey Spillane, it was turning out to be about Evan Hunter.

By mid-1953, St. John, with Meredith’s help, started a campaign to lure big name authors to Manhunt. They approached James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, Rex Stout, Erle Stanley Gardner, Nelson Algren and Erskine Caldwell. They offered as much as $5,000 (about $47,000 today) for a 5,000-word story. This was the kind of money writers could expect from the slick magazines, but not from the pulps.

Many writers like Erle Stanley Gardner initially balked at the idea of publishing in Manhunt, but eventually succumbed. Gardner’s first response to his agent was, “I hate to turn down an offer of $5000 for a story, but, confidentially, I don’t like this magazine concept with which Manhunt started out. I think it is a definite menace to legitimate mystery fiction.â€

By the end of the decade all the big-name writers, including Gardner, had agreed to publish stories in Manhunt, though many appeared only once, the last being the only appearance by Raymond Chandler. His story, “Wrong Pigeon,†previously published only in England, appeared in the February 1960 issue.

The year 1953 would be the peak year for St. John Publications. Manhunt was turning out to be one of its biggest-selling titles, spawning spin-off titles Verdict and Menace, and its 3D comics were selling millions of copies. The company had 35 different comic book titles with several lines of romance comics, Mighty Mouse and Three Stooges comic book lines, for a total of 169 issues published that year.

Another of Archer St. John’s projects was a man’s magazine that would include articles of interest to men, photos of women in various stages of undress and quality fiction. However, he was concerned about the post office not allowing the mailing of what they would certainly deem pornographic material to subscribers. After Playboy appeared in December 1953, he was emboldened to move ahead with the project.

In 1954, Archer brought in his 24-year-old son Michael to help run the business, while he focused on the new men’s magazine, Nugget. Again, he turned to his favorite artist, Matt Baker, to do the illustrations in the magazine. Although that year would turn out to be another good year for St. John Publications, there was trouble on the horizon.

In the spring of 1954, there was a backlash against violence in comic books that were clearly aimed at children. The crusade was led by New York psychiatrist Fredric Wertham who published the now-infamous Seduction of the Innocent, a book-length study of the adverse effects of violent comic books on young minds, and led to a Senate investigation, which issued its own Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency Interim Report that included a list of comic book titles it deemed inappropriate for children. There were, of course, some St. John titles on the list.

It was also apparent in early 1954 that 3D comics were just a passing fad. Sales of 3D comics plummeted to the point that, by March of 1954, 3D titles had all but disappeared. The sales of comic books in general were in a slump, brought on in large part by the scare created by politicians and PTA groups after the Wertham study.

Other forces were coming to bear that would have a personal effect on Archer St. John and the fate of St. John Publications. In August of 1954, President Eisenhower signed The Communist Control Act, which outlawed the Communist Party in the United States. Anyone who had ever been a member of the Communist Party could face imprisonment or even the revocation of citizenship.

Archer’s brother, the famous journalist Robert St. John, living a self-imposed exile in Switzerland and doing research for books on South Africa and Israel, was determined by the FBI to have been a member of the Communist Party. On September 24, 1954, Robert St. John was summoned to the American Consulate in Geneva and stripped of his passport. When Robert asked why his passport was being taken from him, the reply from the Consul-General was that it was because of his Communist Party activity.

Robert turned to his brother Archer back in the States for help to get his passport reinstated and the necessary affidavits for the appeal. Over the following months Archer, who was very close to his brother Robert, became increasingly frustrated by the stonewalling he got from the U.S. government on his brother’s case.

Adding to his personal turmoil was the fact Archer was separated from his wife and living at the New York Athletic Club. His employees at St. John Publications also suspected he was addicted to amphetamines in addition to being an alcoholic. By mid-1955 Robert’s case had still not been decided, though he had submitted numerous affidavits from noted citizens that affirmed that he was never a member of the Communist Party.

In August, Archer told family members that he was being blackmailed, but didn’t give anyone any details. His son Michael told him not to give in to the blackmailers. Archer told his son that he was staying at the apartment of a friend but wouldn’t tell Michael where.

On Friday night August 12, 1955, Robert St. John got a call in Switzerland from Archer in New York who told him, “Never in my life have I felt so frustrated. I feel like I’m banging my head against a stone wall. I see no possibility of my getting your passport back. I’ve done everything in my power to help you, but I’ve failed. I’m sick over this.†The next morning Robert got a call telling him that his brother had overdosed on sleeping pills, an apparent suicide. He was 54 years old.

At times, Archer St. John’s life resembled a story from the pages of Manhunt — Al Capone’s gang once kidnapped him when he was young newspaper publisher — and his death was no different. The apartment where Archer had been staying was a duplex penthouse owned by an attractive, redheaded former model and divorcee named Frances Stratford. She had been sleeping in an upstairs bedroom and had found Archer downstairs lying next to the couch, unresponsive, at 11:30 a.m. that Saturday morning.

A couple had been seen leaving the apartment the night before, and the police were investigating. On Monday, the New York Daily News reported, “A couple of shadowy West Side characters, a man and a woman, suspected of feeding dope pills to magazine publisher Archer St. John, were being hunted … by detectives investigating St. John’s mysterious death in the penthouse apartment of a former Powers model.â€

After St. John’s death, his wife, Gertrude-Faye, known as “G-F†or “Geff,†showed up at the offices of St. John Publications and promptly fired the entire staff, including Matt Baker. Apparently, she hadn’t wanted anyone around who knew about her husband’s affairs. The irony was that none of the staff knew anything about St. John’s private love life, not even Baker who was probably as close to him as anybody.

Despite the failure of the previous Manhunt clones, Verdict, which lasted only four issues in late 1953 and Menace, which lasted two issues, the following year, Michael St. John decided to expand his own editorial staff and to introduce yet two more titles, Mantrap and Murder! in 1956. Unfortunately, the new titles suffered from the same lackluster sales of the first two spin-off titles and were discontinued just as quickly.

Undaunted by the failure of four new titles in as many years, Michael kept searching for a formula that would repeat the success of Manhunt. What Michael and his business manager, Richard Decker, came up with was an opposite, more genteel, direction. They approached Alfred Hitchcock with an offer to license his name and image for a mystery digest.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine was an immediate success and, in fact, sales would steadily increase throughout the rest of the decade while those of Manhunt were in steady decline, down to 169,000 by 1957. Its digest size, with two-column layout and heavily inked spot color illustrations, were identical to Manhunt’s.

In an effort to boost sales of both Manhunt and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, St. John and Decker decided to increase the size of both magazines from their current digest size to regular magazine size to get, what they hoped would be, more attention on newsstands. What it got Manhunt was the unwanted attention of the Federal District Attorney.

After only the second issue at the bigger magazine size, Michael St. John, Richard E. Decker, Charles W. Adams (the Art Director) and Flying Eagle Publications (a subsidiary of St. John’s Publications and holding company of Manhunt) were indicted on March 14, 1957, for “mailing or delivery copies of the April, 1957, issue of a publication entitled Manhunt containing obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy or indecent matter†in violation of United States Penal Code 18 U.S.C. §1461.

In District Court in Concord, New Hampshire, St. John’s lawyers moved to have the charges dismissed on the grounds that the complaint didn’t identify what article was specifically being charged in the issue as “obscene, lewd, filthy or indecent.†They argued that “the indictment is so loosely drawn that it would not afford them protection from further prosecution.†District Court Judge Aloysius J. Connor agreed and threw out the indictments on August 7, 1957.

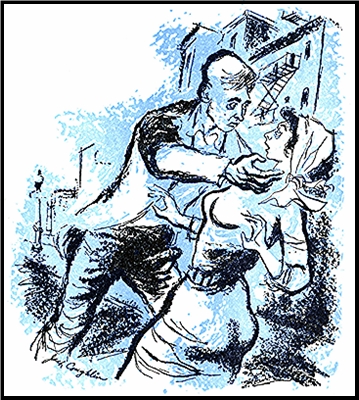

Federal prosecutors promptly refiled charges with specific complaints: “All six of the stories have definitely weird overtones and can certainly be characterized as crude, course, vulgar, and on the whole disgusting. But tested by the reaction of the community as a whole — the average member of society — it seems to us that only the feature novelette, ‘Body on a White Carpet,’ and the illustration appearing on page 25 accompanying the story entitled ‘Object of Desire,’ could be found to fall within the ban of the statute as limited in its application by the important public interest in a free press protected in the First Amendment.†The defendants faced a fine of $5,000 ($43,000 in today’s dollars) and up to five years in prison.

The offending illustration by Jack Coughlin accompanying the story

“Object of Desire†on page 25 of the April 1957 issue.

On December 1, 1958, the final verdict of the District Court jury was that Flying Eagle Publications and Michael St. John were guilty and fined $3,000 ($26,000 today). Judge Connor gave St. John a separate fine of $1000, a suspended sentence of six months in jail and two-year probation. Richard E. Decker and Charles W. Adams were acquitted. Michael St. John immediately appealed the verdict and the case went to Federal Appeals Court.

On January 21, 1960, the Federal Appeals Court in Boston set aside the verdict of the District Court and ordered a new trial. Chief Judge Peter Woodbury found that the prosecutors had erred in their instructions to the jury by telling them that two defendants, Decker and Adams, originally listed on the indictment had “been separated from this action†rather than that they were acquitted.

A year later the Court of Appeals upheld the decision of the Circuit Court on January 10, 1961, and Judge Bailey Aldrich upheld the original fine of $5,000. After three years and nine months of litigation, St. John Publishing was financially drained. The circulation of Manhunt had dropped to 100,000, and Richard Decker had split with St. John in the summer of 1960, taking Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine with him to Palm Beach, Florida.

Scott Meredith had always been annoyed with what seemed to be chronic cash-flow problems at St. John, and it only got worse. The magazine limped along for the next six years, and fewer of Meredith’s writers appeared in the magazine. Only 33 stories by the top ten Meredith contributors appeared in the 1960s.

Only three Evan Hunter stories appeared in Manhunt in the 60s, the last story, fittingly, in the last issue of April/May 1967. By then the circulation had dropped to a little over 74,000 copies. Michael St. John decided to get out of the publishing business entirely and sold off all the assets of St John Publishing, including Nugget.

— From the forthcoming book The Best of Manhunt, Stark House Press, July 2019

Sources:

Aldrich, Baily, Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals, Flying Eagle Publications v. United States, 285 F.2d 307, January 10, 1961

Ashley, Michael, author, Kemp, Earl and Ortiz, Luiz editors, Cult Magazines A-Z: A Curious Compendium of Culturally Obsessive & Curiously Expressive Publications, 2009, Nonstop Press

Benson, John, Confessions, Romances, Secrets, and Temptations: Archer St. John and the St. John Romance Comics, 2007, Fantagraphics Books

Benson, John, Romance Without Tears, 2003, Fantagraphics Books

Fugate, Francis L. and Roberta B., Secrets of the World’s Best-Selling Writer, 1980, William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Carlson, Michael, “Interview with Mickey Spillane,” Crime Time website, June 29, 2002

Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, July 8, 1925, pg. 16

Collins, Max Allan and Traylor, James L, Spillane (to be published in 2020)

Cook, Michael L., Monthly Murders: A Checklist and Chronological Listing of Fiction in the Digest-Size Mystery Magazines in the United States and England, 1982

Horowitz, Terry Fred, Merchant of Words: The Life of Robert St. John, 2014, Rowman & Littlefield

Meredith, Scott and Meredith, Sidney, The Best From Manhunt, 1958, Perma-Books

Morgan, Hal and Symmes, Dan, Amazing 3-D, 1982, Little, Brown and Company

Morrison, Henry, Literary Agent and former Scott Meredith Literary Agency employee (1957-1964), Interview, January 29, 2019

Nashua Telegraph, Nashua, NH, January 22, 1960, pg. 2

Nashua Telegraph, Nashua, NH, January 11, 1961, pg. 2

New York Daily News, New York, NY, August 15, 1955, pg. C5

N. W. Ayers & Sons Directory of Newspapers and Periodicals, 1954-1967

The Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa, Canada, March 2, 1957, pg. 2

The Portsmouth Herald, Portsmouth, NH, March 15, 1957, pg. 7

The Portsmouth Herald, Portsmouth, NH, December 2, 1958, pg. 8

Quattro, Ken, Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could, 2006, www.comicartville.com

Waller, Drake, It Rhymes with Lust, 1950, 2007, Dark Horse Books

Woodbury, Peter, Chief Judge, United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit, Flying Eagle Publications v. United States, 273 F.2d 799, January 21, 1960

Sun 10 Feb 2019

I’ve asked Greg Shepard, publisher and editor-in-chief at Stark House Press, to tell us what’s come out from them recently or what will be showing up soon. He has most graciously agreed:

News from STARK HOUSE PRESS

by Greg Shepard

This year Stark House Press will celebrate being in business for 20 years. Our first book was a hardback collection of fantasy stories by Storm Constantine. We followed that with a few more Constantine projects, then jumped into Algernon Blackwood territory, a supernatural sidestep on our way to crime.

Twenty years in the publishing business has brought us full circle; in January, 2019, we published the definitive biography of Algernon Blackwood by Mike Ashley — The Starlight Man. This is not only the first paperback edition, but also the most complete version, since Ashley added back in all the bits his UK hardback publisher asked him to take out back in 2001, with lots of new pictures as well.

Although our primary focus has mainly been “men’s†hardboiled, noir fiction of the 40s to the 60s — our lead title for January was Lead With Your Left and The Best That Ever Did It by Ed Lacy, two gritty, New York cop mysteries — we recently began adding more of the women’s suspense authors from that era, too. In November of 2018 we issued End of the Line by Bert & Dolores Hitchens as part of our Black Gat series. This is one of five railroad mysteries that Dolores wrote with her rail-detective husband, Bert. But Dolores also wrote a lot of fine standalone mysteries during the 1950s, and we will be bring six of those back over the next couple years, starting with Stairway to an Empty Room and Terror Lurks in the Darkness next fall.

In February, we will be proudly publishing two novels by the incomparable Jean Potts. She won the Edgar Award for one them, Go, Lovely Rose, and was nominated for the other one, The Evil Wish. Both are excellent novels of psychological suspense, the first story dealing with the murder of a woman whom everyone in town hates, the second concerning a murder that is planned but not executed, leaving distrust and suspicion in its wake. Booklist has already labeled these “two masterpieces†and we’re excited to be bringing them back, with more to come.

Stark House will also be reprinting the works of Bernice Carey and Helen Nielsen. Back in November of 2016 we reprinted Woman on the Roof by Nielsen, and in May we have two more of her clever Southern California mysteries to offer: Borrow the Night and The Fifth Caller. Also in May we will be publishing (for the first time in paperback) Carey’s The Man Who Got Away With It and The Three Widows. Carey set her novels in small town California where she lived, often peppering them with her own brand of social justice. As Curtis Evans says in his introduction, “the most significant contribution of Bernice Carey to mid-century crime fiction was her commitment to exploring realistic social conditions in her novels.” She also created some very interesting characters.

Over in the noir camp is one of my personal favorites, Gil Brewer. We published two of his noir thrillers, The Red Scarf and A Killer is Loose, back in October. Brewer was the master of momentum. He’d create a desperate situation for this protagonist—usually involving lots of cash and a young, willing woman — and turn him loose to frantically pursue each with equal amounts of sweat and lust.

This year, we are reprinting Redheads Die Quickly, the definitive collection of Brewer stories edited by David Rachels back in 2012, with five new ones added. And later this year we will be complementing this volume with two new Brewer collections: Death is a Private Eye, set for August, and Die Once — Die Twice, tentatively scheduled for early 2020; each volume edited and introduced by David Rachels.

In March, Stark House is following up its Carter Brown program with three more Al Wheeler mysteries: No Law Against Angels, Doll for the Big House and Chorine Makes a Killing. If you don’t recognize these titles, that’s because No Law was published here as The Body (the very first Brown book to be published in the U.S.) and Doll as The Bombshell.

Back in the late 1950s, when Brown’s Australian publisher started to populate the world with his books, the feeling was that they needed Americanizing. So these first few Wheeler stories were revised for the U.S. audience. I thought it’d be more fun to reprint the original Australian versions, so that’s what we’re doing. In fact, Chorine has never been published in the U.S. at all, so that’s a first for most American readers.

Those are just a few of the highlights. There’s more: Jeff Vorzimmer has edited the mammoth The Best of Manhunt and will be discussing it in a separate post. That’s our big summer title, set for July. I am also working on a second trio of Lion Book noirs, another two-fer of Barry N. Malzberg satires (The Spread and The Social Worker), our final Peter Rabe volume (New Man in the House and Her High School Lover), plus lots of odds and ends over at Black Gat Books, including authors like Noël Calef, Ovid Demaris, Fredric Brown and Louis Malley.

Sat 5 Jan 2019

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

KENNETH MILLAR – The Dark Tunnel. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1944. Lion #46, paperback, 1950. Gregg Press, hardcover, 1980. Also published as I Die Slowly. Lion Library LL52, paperback, 1955.

Ross Macdonald penned his first novel, The Dark Tunnel, in 1944 under his birth name Kenneth Millar. A detective story where the protagonist is a professor rather than a private investigator, the book is best categorized as a work of mystery fiction with strong elements borrowed from the type of thrillers that inspired many a Hitchcock film. Although by no means a flawless work, Millar’s debut novel demonstrates the author’s fluidity with language, particularly the hardboiled vernacular that has become the trademark patois of those writers who have followed in the tradition of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

Published during the Second World War – and soon before Millar entered service in the U.S. Navy – The Dark Tunnel refers to a physical place detailed in one of the more action oriented portions of the novel. It likewise serves as an apt metaphor for Germany’s descent into Nazism. After all, Germany was not some backwater, uncivilized country; it was a country with a rich cultural and literary tradition that nonetheless chose a dark path.

The novel follows the path of Dr. Robert Branch, a literature professor at an unnamed Midwest university set in the fictional town of Arbana (a clear stand-in for Ann Arbor, Michigan). After Branch’s colleague, Alec Judd, informs him of a Nazi spy ring operating in Michigan, Branch is plunged into a nightmarish world of murder and subterfuge wherein he both witnesses one murder and is falsely accused of another. Millar’s academic background – he went on to receive a doctorate in literature after the Second World War – influences his prose, lending the work a frenetic Kafkaesque quality that is more refined than some of his lesser known contemporaries.

Then there’s the girl. A beautiful redheaded German actress named Ruth Esch with whom Branch had a whirlwind romance when he was in Munich in 1937, well before the United States was at war but after the Nazi jackboots had taken power. When Ruth Esch reappears in Arbana, years after being interned in a concentration camp, Branch’s past and present collide in a maelstrom of brutal political violence.

Critics may bristle someone at Millar’s treatment of the dual subjects of homosexuality and transvestitism, both of which play pivotal roles in the unraveling of the mystery and which (Plot Alert) are linked, at least implicitly, with Nazi decadence. These topics, while not overtly exploited for sensational purposes, do lend the work a pulpy, sordid feel that likely shocked some readers when the book first appeared on bookshelves. Some may feel the emphasis on the villains’ sexuality to be a distraction from what is otherwise an impressive tale of an ordinary American man thrust into a world he doesn’t fully comprehend.

More distracting for me, however, was the suspension of disbelief constantly required to accept that a professor of literature would speak in such a hardboiled manner, let alone mouth off to authority figures such as the police and the feds. Robert Branch comes across as a working class PI masquerading as a professor, a product more of the school of hard knocks than of the mandarin university system.

Millar was clearly finding his voice at this point in his career. Academia was the world he knew. So it made perfect sense for him to create a character set in the milieu he best understood. But it’s clear that inside Robert Branch, there was a cynical Lew Archer waiting to get out and make his presence to the world known.

Fri 13 Apr 2018

BERNARD MARA – A Bullet for My Lady. Gold Medal 472; paperback original; 1st printing, March 1955.

I didn’t buy my copy of this book when it first came out, although I might have and I lost or misplaced it later on. But I have had the copy I just read for probably just under 35 years. How do I know? (You ask.) Inside the front cover it has the stamp of a used bookstore I used to go to, a place called Tessman’s, and that’s where I spent all of my spare change when we first moved to Connecticut in 1969. All told, I must have stopped in there on the average of once a week. The price is stamped in, too. All of the paperbacks they had were 20 cents each. Gee, how I’d love to back there today.

But I digress. Bernard Mara was one of two pseudonyms used by the rather famous Irish-born Canadian author Brian Moore. You might recognize him as the author of such novels as The Luck of Ginger Coffey, I Am Mary Dunne, The Magician’s Wife and others. He was nominated for the Booker award three times, and none other than Graham Greene called him “my favorite living novelist.†(Taken from his 1999 obituary in the LA Times.)

Not bad for someone who started out by writing paperback originals for Harlequin-Canada, Gold Medal and Dell:

— as Brian Moore

Wreath for a Redhead. Harlequin #102, Canadian pb original, 1951.

= Reprinted as Sailor’s Leave, Pyramid #94, 1953.

The Executioners. Harlequin #117, Canadian pb original, 1951.

= No US edition; reprinted in Australia by Phantom Books (paperback).

— as Bernard Mara

French for Murder. Gold Medal #402, pb original, May 1954.

A Bullet for My Lady. Gold Medal #472, pb original, Mar 1955.

This Gun for Gloria. Gold Medal #562, pb original, Mar 1956.

= Reprinted as Wild as by Edwin West in a pirated edition (Zodiac pb, 1963).

— as Michael Bryan

Intent to Kill. Dell First Edition #88, pb original, 1956.

Murder in Majorca. Dell First Edition A145, pb original, Aug 1957.

You might find this interesting. Here is how one Internet source describes his early work:

… Following a tentative start as a short-story writer, he began trying his hand at hack thrillers in the Chandler-Hammett mode, under the name of Brian Mara, before taking off into serious fiction in 1955 with

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne.

Other than the books above, only a few of his later books could be described as being mystery-related. Using Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV as a source, they are:

The Revolution Script. Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1971.

The Color of Blood. E. P. Dutton, 1987.

Lies of Silence. Doubleday & Co., 1990.

The Statement. E. P. Dutton, 1996.

Copies of A Bullet for a Lady, in about the same condition as the one I have, are offered on ABE at $30.00 and up. Not bad for a 20¢ investment, and now I really wish I could go back. (And take a look at the prices wanted for the Harlequin editions. They don’t seem to be scarce, but my oh my.)

What I do not think is precisely true is that Moore was writing in “the Chandler-Hammett†mode. I think someone was stretching matters there, using the only names the writer could think of (or thought his readers could identify with). Hammett and Chandler are always used as a crutch by (and for) people not so familiar with the field, when they cannot come up with names on their own.

I’m reminded a little of Eric Ambler myself, but with a hero a little more knowledgeable and capable than some of the innocents (more or less) in Ambler’s work, guys here and there overseas, mostly postwar Europe, who fall into trouble and struggle to get out, and trouble not of their own doing. The adventuresome kind of guy, scraping by, doing this and that, independent and on his own. Jack Higgins’ earlier heroes fall into this category, people like Jack Nelson in The Khufra Run. But since he came along later, then how about Harry Bannock in Edward S. Aarons’ Girl on the Run?

It is no coincidence, I do not believe, that the Aarons book was also published by Gold Medal, nor that later on many of Higgins’ earlier books first appeared in paperback in this country as Gold Medal’s.

The hero in Bernard Mara’s book is Josh Camp, and he is a partner in a small (two person) aviation company based in France, specializing in small jobs that take them all over the world. In 1955, when this book was written, the world was huge, and men who flew around it on their own were greatly to be admired.

When Camp’s partner goes missing in Spain, Josh does not hesitate. He immediately goes to find out what went wrong. And as soon as he lands in Barcelona, he is met by a beautiful woman who tells him that Harry is dead. This is on page 7, and this is where the story begins.

Mara [aka Brian Moore] had a way with words, even at this early stage of his career. Josh checks into the hotel where Harry stayed in Barcelona, and the elderly bellhop leads the way to up to his room. From page 22:

We went up. My room had a thirty-watt light bulb, a bathroom so small you could shave and shower at the same time, and a small balcony looking down at a street as narrow as an alley. A sign on the back of a door said it cost the equivalent of seventy-five cents a night. I gave Grandfather a bill and he left. The place was clean, but being in it made you feel dirty. I took my jacket and shirt off and began to wash. Harry must have been pretty broke to stay here. Not that we hadn’t stayed in worse places when the going was rough. But Spain is the cheapest country in Europe and Harry was on expenses. Still, if he was running from something, the Strasbourg was an ask-no-questions joint.

The language is picturesque, and for readers never more than 200 miles from home, Mara/Moore makes them feel as if they were. I must have led a sheltered life myself. Look at the lady on the cover. If I ever met a lady like that, I know that I wouldn’t be able to say a word. I wouldn’t even begin to know what to say.

In the first 50 or so pages, Josh meets: three women, all enigmatic but beautiful in varying ways; one tough guy; one second- or third-rate toreador; a dwarf; miscellaneous (but not very friendly) cops; and assorted cab drivers and hotel staff. They all have different agendas, especially the three women and the second- or third-rate toreador. All the cops care about is getting Josh out of the country, and they give him only 24 hours to do so. And therefore only 24 hours to discover how Harry’s death happened and who was responsible.

When I got to page 57, I made myself a note. It says, “Do you know what? None of this makes any sense.†On page 67, Mara/Moore rightly decides that a sort of a recap is in order, and by page 84, the true story starts to come out. What it is that the bad guys want and at the same time, to some extent, at least, an idea of who the good guys are.

As you may know, Gold Medal paperbacks in the 1950s were usually only 160 pages long. They could almost be read in a day, and this book is no exception. It may surprise you if I were to tell you that it is the first half which is the more interesting – the half in which confusion is king – but it is so. Once the story rights itself around and heads off in the right direction, it is as if the mystery is gone, as if the story from that point on is a mere formality, as though (but not quite) it’s only going through the motions.

Go figure. An “A minus†perhaps for the first half, and a “C plus†for the second. The works out to a solid “B,†doesn’t it? That’s just about what I would have called it, anyway. If I were still using letter grades.

Thu 3 Aug 2017

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Remember MGM-TV’s THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E.? It was one of the most successful of the many quasi-spy series that flooded prime time in the wake of the early James Bond movies. The stars were Robert Vaughn as Napoleon Solo and David McCallum as Illya Kuryakin, with Leo G. Carroll as their boss, Alexander Waverly. The series ran for four seasons (1964-68), the first in black-and white and the remaining three in color.

I began law school at around the time U.N.C.L.E. debuted but, despite a grueling study schedule, managed to catch most of the first season’s episodes, which were reasonably serious with lots of action. Once the series switched to color it also switched to spoofery and camp. I stopped watching.

But millions stuck with Solo and Illya, and once the ratings showed that U.N.C.L.E. was a hit, MGM-TV commissioned a series of tie-in novels, 23 in all, the first of which was written by Michael Avallone (1924-1999). I had no interest in junk paperbacks but in 1970, when I moved to East Brunswick, New Jersey and was working as a Legal Aid attorney, I discovered that my apartment was only a few blocks from Avallone’s house and called him.

That was the beginning of a weird off-and-on relationship that lasted till his death. Before becoming a neighbor of his I had known very little about him, but after we met I began to collect his books, of which there were dozens. Many of them were movie or TV tie-in novels for which he was paid around $2,000 apiece and which he ground out on his smoking typewriter in a few days or a week. I don’t recall reading any of these, but I did get him to sign them and squirreled them away.

After my wife died and I moved into a condo, I segregated all the tie-in books and put them into a cabinet with sliding doors which were generally kept closed. A couple of months ago I happened to open one of those doors and, since the books were arranged alphabetically by author, discovered a bunch of Avallone that I’d never read, including that MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. novel and two tie-ins from the unsuccessful spin-off series THE GIRL FROM U.N.C.L.E. (1967-68), which starred Stefanie Powers as April Dancer and Noel Harrison as Mark Slate. I decided it was time to tackle the trio.

Avallone’s great contribution to pop culture was the Avalloneism. You can’t pick up any of his 200-odd books without finding yourself awash in lines you’d swear couldn’t possibly have been published. But they were. Thousands of them. Small wonder that I soon began to think of Avallone as the Ed Wood of the written word. These three tie-in books offer further proof that my name for him was not off the mark.

In THE THOUSAND COFFINS AFFAIR (Ace pb #G-553, 1965) Solo and Illya fly to a remote German village to find out what diabolical device killed an U.N.C.L.E. scientist while in his tub and why, just before dying, he put on his clothes backwards.

It’s no surprise that the culprit is a minion of the evil agency THRUSH, a villain called Golgotha who comes straight out of the Weird Menace pulps of Avallone’s teens. Solo solves the puzzle when he remembers that the dead man was a mystery nut with a particular fondness for Ellery Queen—and that one of the best known Queen novels, THE CHINESE ORANGE MYSTERY (1934), had to do with a corpse who was also dressed backwards.

Someone, quite possibly Avallone himself, called the book to the attention of Fred Dannay, who was half of the Ellery Queen collaboration and the closest to a grandfather I’ve ever known. A number of years after the incident Fred told me that he’d been furious with Avallone for having given away the raison d’être of the CHINESE ORANGE puzzle. But Avallone couldn’t understand what the fuss was about. Hadn’t he promoted Queen? In a paperback that sold a gazillion copies, hadn’t he plugged one of the most famous EQ titles?

Whether the book really sold that well remains a mystery. In later years Avallone publicly accused the publisher of having cheated him out of huge royalties. The name in the copyright notice is MGM-TV, and most likely he wrote it as a work made for hire, earning a flat fee and no more. In any event Ace had nothing more to do with him. But a year later, when MGM-TV launched the GIRL FROM U.N.C.L.E. series and made a tie-in book deal with another publisher, it was Avallone who was tapped to write the first two entries, the only ones that appeared in the U.S. although three more came out in England.

More than half a century has passed between the time Avallone’s contributions to the U.N.C.L.E. saga appeared and the time I pulled them out of my sliding-doored cabinet and read them. I was not disappointed.

First let’s take THE THOUSAND COFFINS AFFAIR, which should have won an Edgar had there been such an award for largest number of words misspelled. In a mere 160 pages we encounter such gems as propellor, esconced, earthern (twice!), jodphurs and cemetary. We are also treated to butchered German locutions like dumbkopf, Vast ist?, Seig heil! and nicht yahr.

Illya’s patronymic or middle name, never given in the TV series, is rendered as Nickovetch, which is gibberish. (The genuine Russian name closest to Avallone’s invention is Nicolaievitch, which I happen to know only because it was the patronymic or middle name of Tolstoy.) And there’s hardly a page without at least one juicy Avalloneism. I will show mercy and offer only a handful, complete with page references.

There was something damnedably odd— (19)

The mechanized bug shot over the road, whipping like the mechanical rabbit at a quinella. (41)

Stewart Fromes’ ten stiff naked toes wore no shoes. (57)

Jerry Terry said “Oh!†and that was all. For Napoleon Solo, it said it all. Oh, indeed. (82)

Like a dead fish, Solo’s right arm fell to his side. (100)

The unexpected was always likely to happen when you least expected it. (140)

When we turn to the second and third of Avallone’s contributions to the saga we find more of the same. THE GIRL FROM U.N.C.L.E. #1: THE BIRDS OF A FEATHER AFFAIR (Signet pb #D3012, 1966) not only recycles some of the misspellings like propellor and esconced, it describes one of the bad guys as both a Hindu and a Sikh.

On one page he’s killed by a bullet in the back of the neck and on the very next page we are told that “[b]lood from his blasted skull dripped to the floor.†As if those gaffes weren’t enough, Stefanie Powers’ first name is spelled wrong on the front cover. (That one we have to chalk up to Signet.)

Storywise it’s typical Avallone, with first Slate and then Dancer kidnapped by THRUSH in a plot to swap them for a top enemy scientist, who claims to have discovered the secret of eternal life and is being held at U.N.C.L.E. headquarters. It turns out that the scientist has an identical double who’s operating as a mole inside the good guys’ stronghold but no one in U.N.C.L.E. suspects they might be twin brothers as in fact they are.

At one point while April Dancer is being held prisoner, a THRUSH man relieves her of “her handbag, personal effects, and even her bra (without having had to undress her).†Neat trick if you can pull it off!

Of Avalloneisms the book has no shortage. This time I’ll limit myself to five.

Noise echoed around the room, gobbling up echoes. (20)

“You’re a fool,†the redhead hissed. (23)

His kindly brown eyes were unaccustomably grim. (69)

Her bra, taut from immersion, was strangling her breasts. (72)

The whipsaw wore a long green velvet dress. (80)

Tugs and seagoing freighters mooed like enormous cows in the harbor. (103)

Whoops! Was that six? Just goes to show that quoting from Avallone is habit-forming.

THE GIRL FROM U.N.C.L.E. #2: THE BLAZING AFFAIR (Signet pb #D3042, 1966), in which Stefanie Powers’ name is again misspelled on the front cover, pits our heroic agents against an organization calling itself TORCH and described on the back cover as “so fantastically evil it puts THRUSH to shame!â€

April begins by foiling an assassination plot in the Ruritanian kingdom of Ostarkia, then joins Slate in Budapest before the two of them go on to Johannesburg on the trail of a TORCH scheme to fund its plans for world domination with South African diamonds. There seem to be fewer Avalloneisms this time around, but those that survived the Signet editorial process, such as it was, are choice.

Kurt’s beady eyes roved between them, not sure what they were talking about, not certain as to exactly what to do next. (59)

The colt in the chair was straining at the leash now. (69)

The man with the withered face frowned a frownless frown. (71)

Like so many little men wanting to be bigger than they ever really were in the first place. (126)

In case I’ve whetted your appetite and you’re determined to read more of these cubic zirconia without visiting your shelves or a secondhand bookstore, I’ve put together a much more extensive catalogue from the trilogy, again complete with page references, which I’ve provided because I wouldn’t want anyone to think I’m making this stuff up. You’ll find the bonanza of boners by clicking HERE. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

Wed 28 Jun 2017

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

TULSA. Eagle-Lion Films, 1949. Susan Hayward, Robert Preston, Pedro Armendáriz, Lloyd Gough, Chill Wills, Ed Begley, Harry Shannon, Lola Albright. Suggested by a story by Richard Wormser. Director: Stuart Heisler

I’m going to be honest with you. I enjoyed watching Tulsa way more than I ever expected to. And really, this surprised me. For at the end of the day, there’s nothing all that special about this Technicolor melodrama/modern Western hybrid. Directed by Stuart Heisler, who directed Humphrey Bogart in Tokyo Joe (1949) the very same year, the film stars future Academy Award winner Susan Hayward as Cherokee Lansing, an Oklahoman rancher of mixed heritage who hits it big in the eponymous city’s 1920s oil boom.

When Cherokee’s rancher father gets killed in an accidental oil rig blowout, she decides that the best way to get even with Bruce Tanner (Lloyd Gough), the oilman she holds responsible is for her to join the business herself. Joining her on her ambitious quest to make a name for herself in the oil industry is geologist Brad Brady (Robert Preston) who, to no one’s surprise, ends up falling for the headstrong redheaded beauty. Complicating matters for Cherokee is her longstanding friendship with local rancher Jim Redbird (Pedro Armendáriz), a man who wants no part in Cherokee’s increasingly ruthless and ambitious plans to become an oil tycoon.

What makes Tulsa worth watching, however, is not the rather mediocre and predictable plot. No. It’s that, for a low budget western from the late 1940s, Tulsa has surprisingly lots to say about both environmental conservation and race relations in Oklahoma. Some of it is heavy handed, but a lot of it was perhaps just subtle enough to make an impact on some moviegoers when the film first opened.

Still, if message films aren’t your cup of tea, there’s always Susan Hayward, who is a joy to watch. And there’s a rather spectacular fire sequence at the end of the film, with images of rows of oil derricks up in flames. People must have noticed that intense finale, for it was enough to earn the movie an Oscar nomination for special effects in 1950.

Thu 18 May 2017

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

THE NIGHT EVELYN CAME OUT OF THE GRAVE. Phoenix Cinematografica, Italy, 1971, as La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba. Phase One, US, 1972; dubbed. Anthony Steffen, Marina Malfatti, Enzo Tarascio (as Rod Murdock), Giacomo Rossi Stuart. Direcctor: Emilio Miraglia.

The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave starts off as an uncomfortably sleazy enterprise before transforming into a gripping, moody Gothic thriller. Directed by Emilio P. Miraglia, this stylish Italian giallo film has the typical sex and violence that is prevalent in the genre. But what it also has – what gives the film a little something extra – is a Gothic atmosphere that owes as much to Roger Corman’s cinematic adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories and poems as to the emerging Italian proto-slasher genre of which it is indubitably a part.

Although an Italian film with dialogue in Italian (there’s also apparently an English language version), the movie is set in England. Aristocrat Alan Cunningham (Anthony Steffen) lives a decadent lifestyle in his family’s estate. His wife, the beautiful redheaded Evelyn, has recently died. But not before he was able to confront her about her infidelities. So Alan is a little … mentally unbalanced. So much so that he has a penchant for bringing red headed prostitutes back to his lair so he can have his way with them.

All that changes when he meets Gladys (Marina Malfatti), a stripper who Alan decides is going to be his next wife. All seems well finally for the tormented Alan. But when Alan’s family members begin to die in horrifically mysterious ways, it seems as if he may be cursed. Perhaps his wife Evelyn has indeed come back from the grave to exact revenge. Or maybe someone is playing a giant prank, a cruel trick to send the wealthy Alan over the edge in order to inherit his large fortune.

If you can manage to overlook the giant plot holes in the story, you might just find yourself a bit enthralled with The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave. Although it’s not nearly as good a film as Dario Argento’s output from the same era, it has a stylish flair, some really dark humor, and an effective score composed by Bruno Nicolai.