Thu 29 Feb 2024

Nero Wolfe on Page and (Small U.S.) Screen: Champagne for One by Matthew R. Bradley.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[3] Comments

Champagne for One

by Matthew R. Bradley

Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novel Champagne for One (1958) finds Austin “Dinky” Byne asking Archie a favor: to sub for him at the annual dinner party his aunt, ex-client Louise (Mrs. Robert) Robilotti, throws on the birth date of her late first husband, philanthropist Albert Grantham. At table will be Albert’s twins, Celia and Cecil; unwed mothers Helen Yarmis, Ethel Varr, Faith Usher, and Rose Tuttle; and fellow “chevaliers” Paul Schuster, Beverly Kent, and Edwin Laidlaw. The mothers are “graduates” of Grantham House in Dutchess County, “financed until they got jobs or husbands,” invited to Fifth Avenue to keep in touch…if not necessarily to find said husbands among the upper crust of society.

Forewarned by second-timer Rose that Faith has long kept a bottle of cyanide on her, and might choose that night to use it, Archie watches her carefully until she takes a fatal drink of champagne, and knows she did not administer it herself. Cramer visits Wolfe, making clear in his presence that he thinks Archie is mistaken or lying, but will not rule homicide out; hard on his heels, Laidlaw tries to hire Wolfe to learn why. Believing it was suicide, he fears being arrested for murder if the police uncover the fact that, under a false name, he had a liaison in Canada with Faith, then a clerk at Cordoni’s flower shop, her presence at Grantham House reported to Laidlaw by Byne—apparently unaware he was the father.

Wolfe agrees either to prove suicide or to expose the killer, but mistrusts the “remarkable coincidence” that neither Laidlaw nor Faith knew the other would be there. In return for not revealing that Dinky faked a cold to get out of the party, Archie gets an audience with Mrs. Blanche Irwin at Grantham House, who also doubts suicide and says Byne chose the mothers from the list she gave him. Archie returns home, where Orrie has brought them, and corroborating his statement earns a “quite satisfactory” (“He gave me a satisfactory only when I hatched a masterpiece”) for Ethel; Mrs. James Robbins, a Grantham House director, had gotten Faith a job at Barwick’s furniture store and an apartment with Helen.

Helen recalls that Faith once reported meeting her mother on the street and running away after a scene, but later regretted telling Helen she wished her dead. Two days after hiring Wolfe, with no progress, Laidlaw covers by visiting with the other chevaliers and Cece to accuse him of doing them an injury by linking them with a spurious murder investigation, but the two parties are at an impasse. Archie receives an urgent summons from Laidlaw, dogged by the D.A., as Wolfe is siccing the ’teers on the mother, Elaine, who—per Lon at the Gazette—lammed after authorizing Marjorie Betz to claim the body for cremation; prefiguring the title of a 1963 entry, “I wished the trio luck in their mother hunt and left.”

Somebody mails the D.A. (now Ed Bowen again—I give up) a note outing Laidlaw as the father, yet while he is livid, having admitted nothing, Wolfe is gratified at having goaded the killer into action: “Now he is doomed.” Cramer interrupts the interrogation into who could have known, forcing his quarry to slip out the back and bearding Wolfe in the plant rooms to no avail. Just as Wolfe tells Archie to see Celia, who gave a flippant reason for rejecting Laidlaw’s proposal but may have known about Faith, she calls asking him to the house; on arrival, she admits to being a decoy for her mother, who wants to see him along with the Police Commissioner (now Bob Skinner again—whatever), because of said note.

Asked once again to walk back his statement, Archie tactfully withdraws and, frustrated while waiting for Saul to flush Elaine from her Hotel Christie hideout, blows up at Wolfe. Replying that “You are headstrong and I am magisterial. Our tolerance of each other is a constantly recurring miracle,” Wolfe suggests Byne deserves closer scrutiny; tailing him to Tom’s Joint, Archie finds Saul tailing her there as well, and threatened with the police, they agree to see Wolfe. Separated, Dinky asserts that he’d been intimate years ago with Elaine, who requested the meet to ask about Faith’s death, while she volunteers only the second fact, and during the interview, Orrie arrives bearing a leather case from her room.

This contains a letter from Albert revealing that he had been her lover; supported her and Faith, if not acknowledging paternity due to Elaine’s promiscuity; and arranged for Byne to share with her the annual $55,000 tax-exempt income from a $2 million portfolio. One of the provisions, Elaine confirms, halved her payments if Faith died, and Byne, who now clearly had a motive if not necessarily opportunity, admits he typed the note to deflect the investigation away from him, but got cold feet after mischievously arranging for Laidlaw and Faith to be at the party. Then, as Wolfe leans back, closes his eyes, and start pushing his lips in and out, Archie opines, “I really should have a sign made, genius at work…”

To determine how the crime was committed, Wolfe has Cramer and Stebbins gather the suspects to restage it in his office; Purley voices Wolfe’s observation that the distinctive way Cecil carries the glasses would enable an onlooker to know which of the pair picked up he would proffer to Faith. Waiting in the wings, Elaine is introduced to Louise, who slaps her face, having learned from Byne of Faith’s paternity, and invited her there to kill her. Standing at the bar as Hackett, the butler, poured, Louise dropped the poison into the glass, making her own son an unwitting delivery system, and it is later learned that, aware of the cyanide Faith carried, she procured some, knowing that suicide would be assumed.

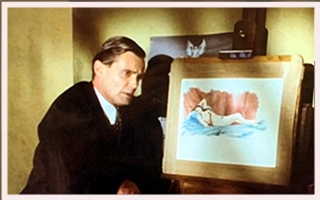

Directed by co-executive producer Timothy Hutton, who played Archie, “Champagne for One” (4/29 & 5/6/01), a two-part first-season episode of A Nero Wolfe Mystery, was the first of four written by William Rabkin & Lee Goldberg; the latter related his experience in a Mystery Scene article reprinted here by Steve. Two of the guest-stars, Marian Seldes (as Louise) and Michael Rhoades (as Kent), made their only other appearances in “Door to Death” (6/4/01), while David Hemblen is credited with one of three as orchid fancier Lewis Hewitt, mentioned in the novella. As in “Prisoner’s Base” (5/13 & 20/01), Aron Tager is billed as “Commissioner Skinn,” although correctly referred to in the dialogue.

Louise’s dislike for Archie, dating to when he and Wolfe (Maury Chaykin) recovered her jewelry, is obvious the moment he arrives at the shindig for Helen (Kathryn Zenna), Ethel (Janine Theriault), Faith (Patricia Zentilli), and Rose (Christine Brubaker). They freshen up after dinner as Archie gets better acquainted with Louise’s son, Cecil (Steve Cumyn); her fortune-hunting second husband, Robert (David Schurmann); and chevaliers Schuster (Robert Bockstael), Laidlaw (Alex Poch-Goldin), and Kent. Then it’s dancing time, with Shostakovich’s Jazz Suite No. 2: VI. Waltz 2, and Kari Matchett, later seen in a recurring role as Lily Rowan, aptly portraying Celia, who also danced with Archie at the Flamingo.

After a fez-wearing Hackett (James Tolkan) pours the soon-to-be-deadly champagne, and Faith collapses, Archie stays by the body while having the band leader (Ken Kramer) call the police. Later, when told why Byne (Boyd Banks) gave Archie an entrée to Mrs. Irwin (Nancy Beatty), Wolfe scoffs, “Nothing is as pitiable as a man afraid of a woman”; Part 2 opens as Saul (Conrad Dunn), Fred (Fulvio Cecere), and Orrie (Trent McMullen) receive their orders. Cramer (Bill Smitrovich) and Wolfe are equally apoplectic during the plant-room confrontation, with Archie recalling the Clara Fox incident from The Rubber Band (1936), while Seldes, again ill-served by her participation in the show, chews the scenery.

When Wolfe confronts her with Albert’s letter, Elaine (Nicky Guadagni) launches herself across the desk at him, and we are treated to the delicious spectacle of Wolfe rearing back to kick her in the chin. Chaykin also beautifully portrays his unprecedented, “unqualified admiration” (“You not only have eyes but know what they’re for”) of the attentive Purley (R.D. Reid), who exchanges glances with a proud Cramer. Despite Hemblen’s inclusion in the credits, I detected no sign of Hewitt whatsoever; since several of the episodes exist in multiple versions for domestic and international broadcast and/or home video, he may appear in one of those, or simply be credited despite ending up on the cutting-room floor.

Goldberg observed that A Nero Wolfe Mystery “was, as far as I know, the first TV series without a single original script—each and every episode was based on a Rex Stout novel, novella, or short story. That’s not to say there wasn’t original writing involved, but it was Stout who did all the hard work…. The mandate from [the] executive producers…was to ‘do the books,’ even if that meant violating some…rules of screenwriting…. More often than not, that meant loyalty to the dialogue rather than to the structure of the plot or the order, locations, or choreography of the scenes.” He and Rabkin adapted Prisoner’s Base (1952), “Poison à la Carte” (1960)—our next post—and “Murder Is Corny” (1964).

— Copyright © 2024 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Up next: “Poison à la Carte”

Edition cited —

Champagne for One: Bantam (1960)

Online sources: