Fri 29 Sep 2023

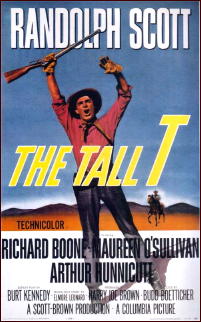

A Western Movie Review: THE TALL T (1957).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[15] Comments

INTRO. Jon and I went to see this as the first film of a Randolph Scott double feature last night. It was showing at the New Beverly Theater in Hollywood, the one owned by Quentin Tarantino. While tempting we didn’t stay for the second feature, but I think a large number of the audience did. The theater wasn’t jam-packed, but as a rough estimate, it was filled to sixty percent capacity, maybe more.

It was good to see the film on the big screen in an actual theater, with an audience that came to see the movie, not to have a party. It also made me wonder if anyone involved in making the film back in 1957 had any idea that here and now, some 65 years later, the movie would still be around to keep fans watching an enjoying.

The review below was first posted on this blog on 19 January 2015.

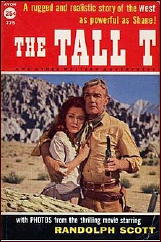

THE TALL T. Columbia Pictures, 1957. Randolph Scott, Richard Boone, Maureen O’Sullivan, Arthur Hunnicutt, Skip Homeier, Henry Silva, John Hubbard, Robert Burton. Screenplay by Burt Kennedy, based on the story “The Captives,” by Elmore Leonard, published in Argosy, February 1955. Director: Budd Boetticher.

To start off with, let me tell you that this is one of my favorite Western films of all time. I won’t tell you that it’s number one, because I’ll be honest with you as well as myself and say that it isn’t, but it’s in the top five.

In part it’s the actors. Randolph Scott isn’t a lawman doing his job with professional dignity and humor, a common role he had in westerns. In The Tall T he’s a struggling former cowhand, no more than that, but he was good at his job. But now he’s living alone and struggling to make a go of his own small ranch, as honest with himself and others as the day is long.

Richard Boone is the villain of the piece, who along with a pair of low-life outlaws he rides with (Skip Homeier and Henry Silva) holds up a stage only to find that it’s not the regularly scheduled one, but one chartered by the man who married the plain-looking daughter of the richest man in the territory, a rabbit of a man who gives up his wife as part of a ransom scheme to save his own hide. Scott, who just happens to be on the stagecoach, is caught up in the plan and as chance would have it, is made a captive too.

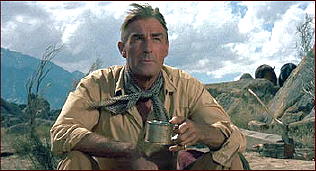

As their captors, Richard Boone and his two cohorts are as murderous and vicious as they come. For some reason, though, Boone lets the yahoos he associates with do all the shooting, and as he confesses to Scott over an open fire, he has a wish to have a piece of land himself. Only Richard Boone could have played the part. A killer who aches with the need for someone intelligent to talk to.

I don’t know how they managed to make Maureen O’Sullivan so plain looking, but she is, and at length she admits that she her knows exactly why her new husband married her. But it’s Randolph Scott who makes the movie work. Rugged, steely-eyed and quiet-talking, but with little ambition more than to make a living on his own, he’s also more than OK with a gun, a fact that in the end turns out to be rather important.

Other than the actors, though, it is the storytelling, the combination of script and directing, that simply shines. The budget probably wasn’t all that large, but the story simply flows, with no wasted moments, every scene essential to the story. This is a movie that’s down to earth and real, and made by professionals on both sides of the camera.

As for Elmore Leonard’s story, the one the movie is based on, you don’t have to read more than two or three pages before you know where the timing and the pacing of the movie came from.

Most of the movie is taken straight from the story, at most only a long novelette, with only a couple of substantial changes. The campfire scene between Scott and Boone referred to above was added, and the way Scott and the woman defeat their captors was re-orchestrated, both changes for the better.

Everyone agrees that Elmore Leonard’s crime fiction was always the best around, but to my mind, his western fiction, which came along earlier, is even better. That includes “The Captives,” beyond a doubt, and the movie is even better yet. To my mind, near perfect.