December 2010

Monthly Archive

Thu 23 Dec 2010

It’s a couple of days early, but I’ll wish you a Merry Christmas and the Happiest of Holidays right now, with plenty of time to spare.

I’ll also take a short break from blogging until early next week. Maybe this bit of time off will give me a chance to get caught up on email, but yes, I know, you’ve heard me say that before.

Thanks to all of the contributors to this blog over this past few months. I’ve learned something from every review and every article you’ve sent me, and from every comment that’s been left. This blog wouldn’t be the same without you.

— Steve

Thu 23 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

WAYWARD. Paramount, 1932. Nancy Carroll, Richard Arlen, Pauline Frederick, John Litel, Margalo Gillmore, Burke Clarke, Dorothy Stickney, Gertrude Michael. Based on a novel by Mateel Howe Farnham. Director: Edward Sloman. Shown at Cinefest 28, Syracuse NY, March 2008.

Showgirl Nancy Carroll marries Richard Arlen, whose very upper-class family is not at all happy with his new wife. They are stuffy and Carroll’s theatrical background and breezy manner alienate most of the family except for a black-sheep in-law (John Litel), who drinks too much and shares Carroll’s dislike of formality.

The family is dominated by Arlen’s mother, splendidly played by a stern and unforgiving Pauline Frederick. Misunderstandings abound until Arlen finally sees through his mother’s duplicity and forces her to back down and accept Carroll into the family.

Carroll, Frederick and Litel bring the film fitfully to life, but Arlen’s inability to stand up to his mother for most of the film makes you wonder what Carroll saw in him in the first place. A ’30s soaper that added little luster to the program.

Editorial Comment: Besides the cast and crew,there’s no other information about this film on IMDB — no synopsis, no comments, nor any other external links. There has never been an official release, and in all likelihood there never will be one. Quite surprisingly, though, if you were so inclined to try, you should be able to find a copy on DVD rather easily on the collector-to-collector market.

Wed 22 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

DONALD HAMILTON – Smoky Valley. Dell First Edition #18, paperback original; reprinted several times, first by Dell, then Fawcett Gold Medal.

◠THE VIOLENT MEN. Columbia, 1955. Glenn Ford, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward G. Robinson, Dianne Foster, Brian Keith. Based on the novel Smoky Valley by Donald Hamilton. Director: Rudolph Maté.

A while ago on this blog I mentioned a pleasing little Western called The Violent Men (Columbia, 1955), and last month I managed to seek out the book it was based on, Smoky Valley, by none other than Donald Hamilton.

It turned out to be a fun read, and no less interesting to see how it was re-jiggered for the movie.

Smoky Valley tells the brief story of John Parrish, a broken Civil War vet come west for his health, and it picks up just as the neighbors who nursed him to recovery are being forced off their land by a nasty rancher and his nastier son-in-law, who own that icon of the genre, The Biggest Spread In The Valley, and mean to make it bigger.

In the way of Western good-guys, Parrish avoids conflict as long as possible and even eats a certain amount of dirt before striking back with that cool, deadly efficiency a writer like Hamilton puts across so well.

Indeed, it’s Hamilton’s quiet-but-deadly prose that lifts this thing out of the ordinary. Hamilton knew about guns, horses and men, and he could structure a story to show off his skill with them.

This was translated very ably to the screen in the movie; one particularly remembers Brian Keith casually loading his gun while everyone else talks about settling this thing peaceably, or Parrish (Glenn Ford) coolly murdering a gunman — both scenes straight from Hamilton’s book, tautly written and ably filmed.

But the main difference between page and screen is Barbara Stanwyck. I don’t know what led Columbia to put Stanwyck in this film. Her character doesn’t appear in the book, but once she was in it, they had to build up a good part for her.

And they sure did. Playing the cattle baron’s dissatisfied trophy wife (starring again with Edward G. Robinson ten years after Double Indemnity) she projects her dominant personality against a back-drop worthy of her, somehow without overbalancing the story. Neat trick, that.

We still get the basic elements and the full flavor of Hamilton’s tight little novel, with the added attraction of a fine actress at her bitchiest, particularly in a definitive moment when she shows her love for her crippled husband by throwing his crutches in the fire as hes trying to escape a burning house.

Tue 21 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

The Good Witch of Laurel Canyon. Premiere episode (of 12) for the CBS TV series Tucker’s Witch, 6 October 1982. Cast: Rick Tucker: Tim Matheson; Amanda Tucker: Catherine Hicks; Ellen Hobbes: Barbara Barrie; Marcia: Alfre Woodard; Lt. Fisk: Bill Morey. Guest cast: Danny: Ted Danson; Babs: Alexa Hamilton. Created and written by William Bast and Paul Huston. Director: Peter H. Hunt.

Husband and wife PI’s Rick and Amanda Tucker hunt for the person who is strangling married women in high-rise elevators. Want to guess how it ends?

The gimmick for this series is an odd one. Amanda is a witch. However this is no PI Bewitched. Amanda is trying to learn to control her special powers, special powers that is public knowledge.

The acting, especially Catherine Hicks, is the only thing going for this series, and some would claim the occasional cheesecake views of Hicks is the only reason to watch.

Before the opening credits we watch the killer in action. What follows is not some Columbo-like mystery, but instead a cliche-filled, lazily written romantic comedy mystery that fails in nearly every way possible.

Need to find a clue? Let the witch have a hunch about something and you have your clue or if she is wrong you have your comedy.

Feature a Los Angeles police department that accepts hunches from an unreliable witch, as well as does not notice all the victims were members of the same video dating service. A video dating service that gives all its members a pointless charm for no reason other than the writers need a clue for their witch to find.

Nearly every TV mystery cliche is in this one episode. Rick does not want to talk about the case because he wants to go on vacation (no signs they are packed to go anywhere). Seconds later they get a call that a client wants to hire them for this mystery. Rick tries to convince the paying client to drop case. Flighty sweet Amanda’s Mother who lives with them.

Wacky neighbors. Understanding stupid cop friend. Woman overhears them discuss the murders in first person and misunderstands. PIs break the law stealing personal property to find out who did it. They are so obvious about it the killer finds out. Killer tries to kill Rick in a car by cutting the brake line. Spend screen time watching the “out of control” car run over things.

Killer decides to make Amanda the next victim. Rick rushes to her rescue (though Amanda does hold her own vs the killer). Episode ends with cute bit where the loose ends are summed up during adorable characterization action.

You know you are watching bad 80’s network TV when the smartest character is Dickens, Amanda’s cat who uses the phone answering machine to let Rick know Amanda is with the killer. Top that, Lassie!

Reviewed from YouTube videos: Part One.

Tue 21 Dec 2010

From detective fiction researcher John Herrington comes the following inquiry, which I paraphrase:

I have been looking for Jay Shane, an author who published a couple of westerns for Robert Hale in the UK. I thought it might be a pseudonym until I found the blurb below on Amazon. According to Social Security death records, the dates are correct.

So far I’ve only found a couple of westerns by him, as well as various works on TV repair etc. I wonder if you can post something on your blog to see if anyone can identify his crime fiction, or anything else he wrote.

Here’s the Amazon blurb:

“Jay Shane, the author of both Western novels and Technical literature was born in 1911 in Saskatchewan, Canada. Mr. Shane passed away just two months after having finished the writing of this novel in April of 2009 at the age of 97. Mr. Shane made his living repairing Color Televisions and owned and operated a shop for most of his career. His avocation however was writing and had successfully published many fiction including Westerns and Detective novels and wrote technical articles for the TV repair industry other non-fiction books and articles for the electronics industry. Always interested in character profiles, Mr. Shane had researched extensively the social and cultural characteristics of the time period for this novel in an effort to accurately represent the kind of world in which the Apostle Matthew would have lived.”

Sun 19 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

REVIEWED BY J. F. NORRIS:

CHARLES FELIX – The Notting Hill Mystery. Bibliographic information included in the essay that follows.

I have had a book hanging around my home for about the past five years, and I vaguely recall moving it around from box to box for some time. It is an anthology with the rather bland title of Novels of Mystery of the Victorian Age (Pilot Press, UK, 1945; Duell Sloane & Pearce, US, 1946) and weighs in at a hefty 800+ pages.

Only last month did I finally open the thing. The title hinted at what I hoped would be a book of forgotten tidbits that I would keep me busy reading for a few weeks, but a quick scan of the Table of Contents told me why I left it untouched in a box for so long. Of the four “novels” listed only one really qualified as such and the other three were more novellas.

Three of the titles were extremely familiar and (in my opinion) not worthy of inclusion as they have remained in print since their initial publication. Those long lasting works are: The Woman in White, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde and Carmilla.

The fourth title, however, gave me the reason as to why I hung onto the book. That title is The Notting Hill Mystery — a book I remember coming across in a list of noteworthy detective novels reissued back in 1976 by Arno Press as its first US edition, and even so a rather scarce book in the antiquarian trade.

A quick flip through A Catalogue of Crime shows that Jacques Barzun also came across the novel in the same anthology and wrote a laudatory one paragraph blurb. Maurice Richardson’s introduction to the story in Novels of Mystery was like a really good movie trailer — it piqued my interest enough without giving too much away, and I decided then and there to read the thing at long last.

Well, I was utterly surprised by what I found in the pages. It turned out to be a detective novel and a true mystery and much to my delight included the perfect blending of the cerebral and the bizarre. It was — to be blunt — right up my alley!

First a prelude about the author. In this anthology the author is listed as it was in the book’s original published format, as a magazine serial, when its author was “by Anonymous.” [Once a Week: An Illustrated Miscelleny of Literature, Art, Science & Popular Information, circa 1862-1863.]

Since then there has been some scholarly research to determine that the first book format of The Notting Hill Mystery (London: Saunders, Otley, 1865) changes Anonymous to “Compiled by Charles Felix from the papers of the late R. Henderson, Esq.”.

Richardson makes brief mention of Felix in the introduction to the novel and that at the time little else had been uncovered about Felix. That could be because Charles Felix is clearly a pseudonym, since the “papers” and “R. Henderson ” are all fictional.

Hubin lists only three books attributed to Felix. I have been unable to locate any of the other titles. Certainly I’d be interested to see if he was as innovative in the other stories as he is in The Notting Hill Mystery.

[ *** PLOT ALERT *** The remainder of this essay, more than a mere review, may reveal to the discerning reader more details of the plot than you may wish to know. ]

I also learned why Richardson chose to place it in the same volume with Collins’ masterful sensation thriller. It is definitely influenced by The Woman in White, with which it shares the basic plot of a sinister husband attempting to win his wife’s fortune by criminal means.

The title is, however, somewhat of a misnomer. It should more accurately be called The Notting Hill Mysteries for it presents the reader with no fewer than four genuine mysteries and three mysterious deaths.

◠Mystery #1 – What happened to the kidnapped sister?

◠Mystery #2 – How can a woman be poisoned yet no trace of poison remain in her body?

◠Mystery #3 – What can drive a clearly innocent person to commit suicide prior to a murder trial?

◠Mystery #4 – When is murder not really murder? Or this corollary – can murder be committed and yet not ever be classified as such?

The typically involved Victorian plot tells us straight off that a woman has died what follows is an investigation into her questionable accidental death. The culprit’s identity is hinted at the onset.

This may lead the reader to think that story will be something of the inverted variety so masterfully executed in later years by R. Austin Freeman and Francis Iles. Make no mistake — the book indeed will develop into a detective novel of the fair play variety (perhaps teetering on the brink of “fair play” as we know it).

Our narrator begins with the tale of a woman who gave birth to twin girls then died shortly thereafter. We are told that the two girls though not identical in appearance are nonetheless almost of one mind — “in effect psychically linked.”

One girl often managed to feel things that the other was experiencing and vice versa. We follow the story of one of those daughters (Gertrude Bolton) while the other (Catherine Bolton) we eventually learn is abducted by gypsies. Gertrude was a sickly child all her life, and when she marries William Anderton he tries to cure her chronic illnesses. He tries all sorts of remedies and this leads him to experiment with the latest trend -– mesmerism.

Then we are introduced to Baron R** and his assistant Madame R**. Madame R** we learn through various means is actually Charlotte Brown, a former tightrope walker with a traveling circus, who later changed her name to Rosalie when she joined the Baron after he discovered she had clairvoyant powers. [FOOTNOTE]

Perhaps I should mention now that the story takes the form of an epistolary novel with a central narrative written by an insurance investigator who submits supporting documents made up of various sworn testimonies, and letters that further explain the mystery surrounding the multiple deaths.

At this early stage, the reader is presented with mystery number one – what happened to Catherine Bolton, the girl abducted by the gypsies? It is fairly easy to solve although it is not officially announced until much later in the story.

Mystery number two is revealed in the relationship between Madame R** and Gertrude Anderton. Here is the first truly weird or supernatural element: Madame R**/Rosalie’s clairvoyant powers seem to be more of a paranormal empathic relationship with Gertrude, for they feel the same things both emotionally and physically.

Rosalie manages to take on Gertrude’s illness and heal her. Similarly Gertrude begins to feel things that affect Rosalie. And the main plot of the story uses this supernatural aspect to reveal to us that Gertrude is feeling the effects of a slow poisoning that really is being experienced by Rosalie. (Have you perhaps solved mystery #1?)

Then the story shifts focus to the diabolical Baron and how he cares for his now ailing wife Madame R** (aka Charlotte Brown, aka Rosalie, aka you’ve probably guessed.). Along the way circumstances lead the police to fingering Gertrude’s husband as the prime suspect, and that too will lead to tragedy.

There is also the slow reveal of a plot a bit similar to that crafted by Sir Percival in The Woman in White. How the Baron manages to concoct his devilish scheme and carry it out to its terrible conclusion is something one might expect in a modern crime novel than in a story of the Victorian era.

To a modern reader The Notting Hill Mystery may be filled with Victorian contrivances, coincidences and a dash of far-fetched fantasy. I always discount and wholly ignore these picayune criticisms of Victorian era novels. Contemporary readers tend to deny that coincidence has no place in modern literature, when in fact real life abounds with coincidence.

And all fiction is in effect fantasy, therefore I’m always willing to allow for the far-fetched no matter what the genre. Keep in mind that this story was originally published serially in 1862 only a few years after The Woman in White (1860) but earlier than The Moonstone (1868) and decades before books more well known with similar plots.

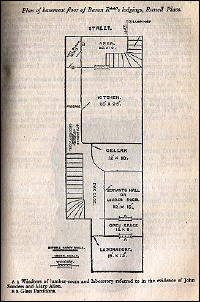

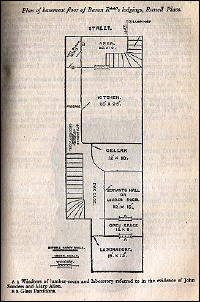

I find the story to be filled with originality –- a brilliant spin on a familiar theme. It must have seemed very new to readers in 1863. Although the epistolary format was common for narrative stories at the time, certainly turning the story into a dossier of sorts with illustrations like floor plans and facsimiles of a letters and marriage certificate was an original idea. Even the means by which each murder is committed (including one which can only be classified as supernatural) are ingenious for genre fiction at the time.

There are quite a few surprises that pile up as the final documents in the case are presented. Perhaps the most stunning surprise comes when the insurance investigator in his summation of the entire sinister affair presents us with Mystery #4 mentioned above and leaves it up to his readers to come to their own conclusion.

FOOTNOTE: The characters really are named Baron R** and Madame R**. That’s not a typo or some Internet glitch. That’s how the names appear in the text throughout the story.

FELIX, CHARLES. Pseudonym of John Retcliff.

-Velvet Lawn (n.) Saunders 1864.

The Notting Hill Mystery (n.) Saunders 1865.

-Ram Dass (n.) Tinsley 1875.

— From the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

[UPDATE] 12-20-10. Jamie Sturgeon emailed me this morning to point out that in Part 38 of the Addenda to the Revised CFIV, Al Hubin has removed John Retcliff as the man behind the Charles Felix pseudonym.

I asked Al for further details, if he had them. Here’s his reply:

“If you google “Charles Felix” “and “John Retcliff” you’ll come across a book dealer’s offering of “Once a Week” by Felix. There’s a long discussion of authorship, and it turns out John Retcliff was a made-up name by Herman(n) Goedsche, 1815-1878, a Prussian secret agent. It’s not clear to me that Goedsche wrote the Felix title, though folks seem to imply that he did. I’ve seen a list of Goesche/Retcliff(e)’s writings, which did not include the Felix titles. So, for me, the authorship of the Felix material is still up in the air.”

Jamie also sent me a copy of Julian Symons’ article in the The Times in which he discusses The Notting Hill Mystery and its place in the history of the early detective novel. It doesn’t appear to be online, but if you’re interested perhaps I can forward the article on to you. Email me offlist, if you would.

Sun 19 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

ARTHUR LYONS – False Pretenses. Jacob Asch #11. Mysterious Press, hardcover, January 1994; reprint paperback, March 1995.

Arthur Lyons has been writing about Jacob Asch for 20 years now, which makes him one of the elder statesman among hardboiled PI writers still writing. Most would grant him a place in the top ten, and some higher.

Asch is feeling middle-aged about it all lately, and has been reduced lately to certifying incompetents for conservatorships, so he welcomes the chance to follow a wife for a man who is suspicious of her. She does nothing off-key, but when he returns to his office he finds the husband dead in the chair behind his desk, his brains splattered all over the wall.

He wasn’t who he said he was and neither was she, Asch finds as he begins to try to sort out what and why. While doing this he meets a statuesque LAPD Lieutenant, and this gives rise (pun intentional) to more complications.

Lyons does the usual competent job of telling his first-person story, with minimum description and terse, no-frills prose. Asch is a bit more active sexually than I remember from past books, but otherwise is the same old lone wolf PI driving LA’s mean streets.

It would have been a good, though not exceptional book but for one thing: the plot. To give it the necessary surprise ending, Lyons has Asch make an intuitive connection that is utterly without foundation, and from there comes up with an explanation that I didn’t believe, and that was built wholly in the last 90 or so pages. It turned an average book into one I disliked. First Valin, now Lyons. [Darn.]

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #10, November 1993.

Previously on this blog:

Death Noted: ARTHUR LYONS (1946-2008). Includes a complete bibliography, with many cover images.

Movie Review – SLOW BURN (1986). Made for Cable TV film based on Castles Burning. (Review by Steve Lewis.)

Editorial Comment: This is the first time I’ve edited one of Barry’s reviews for this blog. The original final sentence seems to have referred to an ongoing apazine discussion of the “death of the PI novel,” but I couldn’t find the exact reference, nor I could I have repeated the entire conversation even if I had. So I replaced it by a single word [in brackets] which I hope expresses Barry’s displeasure at being disappointed by two of his favorite authors.

For what it’s worth, and you can read into this whatever you wish, False Pretenses was the last of eleven books in Arthur Lyons’ Jacob Asch series.

Sat 18 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

JONATHAN VALIN – The Music Lovers. Harry Stoner #10. Delacorte, hardcover, March 1993. Reprint paperback: Dell, April, 1994.

Harry Stoner is going through a bad patch. He’s middle-aged, his lady is out of town, business is slow, and he’s damned near broke. Then a little man about his age comes in and wants him to recover some stolen records; vinyl, collector-type, that is.

And he knows who took them, he says – another collector. Harry, needing money, accepts. Needless to say, it gets a lot more complex than it first seemed, and violent – though far from as violent as a typical Harry Stoner tale.

I really hate to say this, but Music Lovers wasn’t very good at all. Certainly it isn’t the type of book one expects of Valin. He is still a competent prose-smith, and that’s about the best I can find to say.

Though I did enjoy the bits about record collecting, I never believed the story, and I couldn’t believe in the characters (who lacked any edge, and would have been much more at home in another kind, any other kind, of book) or in their relationships.

The interplay between a bigot and a black man was in particular excruciatingly false and unbelievable. In this book Stoner was nothing more than a cookie-cutter PI who did stupid and unrealistic things. including withholding the whereabouts of a wanted murderer from the police for the flimsiest of reasons.

I hope Valin just had one of those days, and hasn’t burned completely out. I’ve heard people who’ve never tried him before say that they enjoyed this; maybe so, but if you’re a Stoner fan already, don’t bother – you’ll be disappointed.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #9, September 1993.

Previously on this blog:

Final Notice (reviewed by Steve Lewis). A complete listing of the Harry Stoner series follows the review. There was only one more to come after The Music Lovers.

Fri 17 Dec 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Crider:

RICHARD DEMING – Anything But Saintly. Permabook M-4286, paperback original; 1st printing, August 1963.

Richard Deming wrote original mysteries and novelizations of numerous TV series, including two books based on Dragnet. The two Dragnet books appeared in 1958 and 1959 and perhaps led to Deming’s writing his own police procedural series in the early 1960s.

Although the series was only two books, it was competently written and entertaining. The setting of both books is the riverside city of St. Cecelia, and the first-person narrator is Sergeant Matt Rudd (real name Mateusz Rudowski), a member of the city’s Vice Squad.

In Anything but Saintly, a businessman visiting the city is rolled by a prostitute and robbed of $500. Rudd and his partner, Carl Lincoln, set out to recover the money, only to find that the girl was murdered shortly after returning to her apartment.

Being a member of the Vice Squad does not keep Rudd from getting involved in the killing, because an attempt is soon made on his own life. What looked at first like a simple case suddenly escalates into something more, with a heavily protected procurer and a big-time politico getting dragged in.

The procedural details, including the peculiar workings of the St. Cecelia Police Department, are well done, and the story is terse and fast, with a good depiction of a racket-ridden city and how it is run.

Matt Rudd appears again in Death of a Pusher (1964). An equally good, but very different, paperback original by Deming is Edge of the Law (1960). He also created a one-armed private detective, Manville Moon, who appears in three novels published in the early 1950s, beginning with The Gallows in My Garden (1952).

Other of his mysteries appeared under the pseudonym Max Franklin, notably Justice Has No Sword (1953).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: Unknown to Bill or anyone else at the time 1001 Midnights was published, Matt Rudd had appeared in one other novel, Vice Cop, published in 1961 by Belmont Books, a small and mostly obscure company known today by only the most dedicated of collectors.

Fri 17 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

RICHARD DEMING – Hit and Run. Pocket #1271, paperback original; 1st printing, February 1960. Expanded from a shorter version that appeared in Manhunt, December 1954.

Richard Deming was a hack, and generally not a very inspired one, but he managed a couple of mildly interesting efforts, including Body for Sale (1962) and Hit and Run (1960.) Other than that, it was mostly bland novelizations, some TV-tie-ins and even ghost-writing for Alfred Hitchcock and Ellery Queen.

Hit and Run starts off with PI Barney Calhoun witnessing (did-you-guess?) a minor hit-and-run accident committed by a pair of illicit and wealthy lovers. But when he approaches them, it’s not for blackmail but for performing the very real service of getting them out of trouble and smoothing things over with the law while hiding their involvement.

As you’d expect in a story like this, things spin very quickly out of control when it develops that the accident was more serious than it looked, and the woman in the case won’t stop at murder to cover her tracks.

This is mostly a very skillfully-worked job, and Deming offers some pleasing chills as Calhoun finds himself getting in deeper and deeper till the only way out is …

Well, I won’t reveal too many twists, but there are several in Hit and Run, and they’re pretty nicely handled till the wrap-up, which strains credulity (mine anyway) entirely too far, with the sort of stretchy coincidence a writer like Woolrich could carry off, but one like Deming fumbles badly. Which I suppose is the difference between a poet and a hack.

Editorial Comment: This is Barney Calhoun’s only case to have seen print.

Next Page »