by Francis M. Nevins

For my last column I revisited one of the Bertha Cool/Donald Lam novels written by Erle Stanley Gardner as A.A. Fair, and for this one I tackled another. Fools Die on Friday (1947) is more straightforward than Bedrooms Have Windows and the plotting more under Gardner’s control.

The firm is hired to protect a real-estate tycoon from having his food poisoned by his second wife, who married him after his first wife died of, you guessed it, food poisoning. Donald quickly catches on that his new client isn’t who she claims to be. Then he devises a scam to delay the poison plot by posing as PR man for a manufacturer of anchovy paste and offering to put Wife Two in ads for the product.

The realtor is poisoned anyway — with arsenic in the paste Donald left at his house as samples — and so is his wife. He recovers but she doesn’t. Then his secretary is strangled and Donald finds the body. Mixed into the ragout are a devious dentist, a machine that handicaps horse races, and a wandering package of arsenic.

There’s very little detection in this opus, but the pace is furious (as usual with Gardner) and the climax, with one character literally getting away with murder, would never have been allowed in a contemporaneous Perry Mason novel since the Masons were being serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and the Cool/Lam books weren’t.

Among other dividends in Fools Die we get to learn a new word. In Chapter 5 Cool tells Lam she’s trying to get the firm’s client “in a position where she has to pungle up more money.†In Chapter 15 she asks him: “You pungled up a hundred bucks in cold cash on the nose of one pony on the strength of it [i.e. the handicapping machine]?â€

I’ve never seen the word before in my life but Webster’s New International Dictionary assures me that it’s a genuine verb, meaning to pay or contribute. I wonder where Gardner came across it.

Ever hear of Walter Kaufmann? He was born in Germany of Jewish parents in 1922, left his homeland on a scholarship to an American college just before Hitler launched World War II, returned to Germany with Military Intelligence during the war, and eventually was hired by Princeton University as a professor of philosophy. I discovered him in my teens and have been reading him all my life.

Why am I recounting all this here? Because in one of his best-known books, Critique of Religion and Philosophy (1958), he tossed off a comment about our genre that is well worth preserving:

The balance of this sentence is for our purposes (if I may cite a Gardnerism) incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that among Kaufmann’s favorite whodunits were those in which the detective acted as historian, for example Ellery Queen’s The Murderer Is a Fox (1945) and Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time (1952).

We’ll never know for sure. Kaufmann died horribly in 1980 at age 58. Anyone interested in the details can access his brother Felix Kaufmann’s account of his death by googling both men’s names.

Still bogged down as I am in the index for The Art of Detection, I’ll pad out this column to its usual length with the help of that nonpareil, that nonesuch, that Ed Word of the written wood, Michael Avallone.

Over the decades I’ve culled from his 200-odd novels well over a thousand prime specimens of the Avalloneism. Both Bill Pronzini and I as well as some others have offered samples taken from his Ed Noon PI novels, but readers of this column are less likely to have seen those he perpetrated in the dozens of paperback Gothics he wrote under female bylines back in the Sixties.

From The Second Secret, as by Edwina Noone (Belmont pb #B50-686, 1966) I’ve harvested 7½ single-spaced pages of howlers, which I hope to dole out over the next several columns. Page numbers are provided in case anyone wants to quote these in an academic journal. Hold onto your hats and here we go:

He had been gone four long years and Cherry Williams had never stopped loving him. Like the red oak tree, she could not remember a time when she hadn’t loved dark-haired, handsome, surly Adam Freneau. (10)

The sturdy frame of his muscular young body, presaging the manhood that was to come, had engraved itself on her heart. (11)

She had only to say his name to herself or see his face in her fancies and the blood in her body would stir warmly. (13)

Cherry felt her heart stop beating, the lungs in her bosom squeeze unbearably. (14)

For a wild second, she wanted to run.

But her legs refused to heed the random irresolution of her mind. (14)

The tone of the words were worldly weary, yet unmistakably condescending. (16)

A mammoth, all-encompassing scarlet flare of color seemed to paint the world in flaming colors. (19)

(B)oth women could now hear the far off clang and trumpetry of the fire bells strategically placed all over Englishtown and vicinity. (20).

Miraculously, the stone pillars and colonnades had held off the worse that the flames could do. (20).

Of course, any number of Avallone’s Gothics are utterly devoid of such gems. When I find one of these I usually fling it across the room, snarling: “Why did I pungle up good money for this garbage? Someone edited it!†But so many of his immortal works are so lavishly studded with verbal cow pies that I could keep quoting like this till at least my 90th birthday. If there should be one.

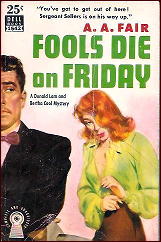

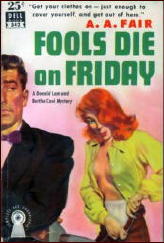

[Editorial Comment.] 11-7-12. By the time Dell got around to reprinting their 1951 edition of Fools Die on Friday (#542), the first cover was considered risque enough that some changes had to be made. See below: