Turn this one way up. The neighbors won’t mind.

February 2019

Fri 15 Feb 2019

Music I’m Listening To: TOM JONES & RHIANNON GIDDENS “St. James Infirmary Blues.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[4] Comments

Thu 14 Feb 2019

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: NOTORIOUS (1946).

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance , Reviews[6] Comments

NOTORIOUS. RKO Radio Pictures, 1946. Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains, Louis Calhern. Screenplay: Ben Hecht. Director: Alfred Hitchcock.

A lot of ink has been spilled on interpreting Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, the romantic thriller starring Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman. Some critics have posited that the film is primarily a romance in which love, despite numerous obstacles, ultimately triumphs at the end; others that it belongs in that every amorphous cinematic category known as “film noir.â€

Others have focused less on the film’s plot and more on its signature visual style and the manner by which Hitchcock creates and refines the very language of cinema. The one through which he is able to tell the story through both the placement of inanimate objects and the imposition of meaning to them.

All of the above, I think, are valid ways in which to interpret Notorious. I personally have my doubts whether this particular RKO release should be considered a proper film noir. Yes, it’s on the more cynical side of things and its subject matter – in which the U.S. government through the persona of one of its agents, T. R. Devlin (Cary Grant), essentially prostitutes Alicia, a deeply damaged young woman and the daughter of a convicted Nazi spy (Ingrid Bergman), persuading her to infiltrate a group of Nazis in postwar Brazil – is obviously less pure than many of the morale boosting films put out by the major studios during the Second World War. But it’s a far cry from the cynical and gritty lower budget crime dramas that are now rightly considered films noir.

For me, the film is essentially about losing and winning, both on the personal level (romance) and on the political (thriller). It’s the universalism of this subject matter that makes it compelling to viewers seventy some odd years after it first premiered. The plot, as Hitchcock himself agreed, boils down to a man who is forced to choose between his emotions (his love for Bergman’s character) and his duty to his country.

More significantly, it’s about Devlin’s desire to win at nearly any cost. He wants to win Alicia over his competitor, the Nazi industrialist (Claude Rains) whom she has been spying on for Uncle Sam. He wants his country to win over the Nazis even after the war has ended. There’s rarely a moment in the film in which Devlin ceases to want to win on both a romantic and political level. There is no “dark night of the soul†for Devlin in which he questions his ultimate desires and goals.

If we are to see Alicia as the film’s main character – and I think she is – then the question becomes whether Notorious is fundamentally all that different from other motion pictures about women who want to change their lives. As the film’s title indicates, she’s notorious. She drinks and has numerous love affairs with men. Devlin knows this. Yet he’s deeply conflicted about it, which is why he is alternatively madly in love with her and deeply cruel to her.

By the end, she thinks that she has changed, that she has found her white knight in Devlin who carries her down the stairs and out of harm’s way. But no one realistically thinks that this is a fairy tale ending. Once the mission is complete and Devlin realizes he has won against the Nazi villain in two ways, will he want to stick around to “make things work,†as modern family therapists would say, or will he be poised for the next assignment?

I should note that I recently watched the brand new Criterion Collection blu-ray release of this Hitchcock classic. There are some truly worthwhile supplemental features including an illuminating 2009 documentary about the film in which the political context at the time of the film’s writing and release is discussed by leading film critics and historians.

Of note is the fact that soon after the Nazi concentration camps were liberated, Hitchcock directed a short documentary film about the horrors discovered there. This was one of his main completed projects before working directing Notorious, which of course features Nazi industrialists who have relocated to South America after the war’s end.

In 1946, the Cold War hadn’t yet made West Germany a vital ally to the United States so Nazis, rather than the communists, were still the villains. It’s doubtful whether such a film would have been of as much interest to studio executives had screenwriter Ben Hecht and Hitchcock pitched the film in 1950.

Thu 14 Feb 2019

Music I’m Listening to: MILES DAVIS “My Funny Valentine.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Wed 13 Feb 2019

Archived Mystery Review: M. D. LAKE – Amends for Murder.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews[5] Comments

M. D. LAKE – Amends for Murder. Peggy O’Neill #1. Avon, paperback original, November 1989.

A frustrating book. There aren’t many detectives who are female campus cops, and the idea produces lots of good possibilities, most of which are only hinted at in this book. Peggy O’Neill is her name, and she’s the one who finds the body of a murdered professor of English.

Determined to show the city police a thing or two, Peggy then uncovers some of the dead man’s more unseemly past. What bothered me was the way she knew things before she (and the reader) was told, and the way the killer was caught, by sheer accident.

The Peggy O’Neill series —

1. Amends for Murder (1989)

2. Cold Comfort (1990)

3. Poisoned Ivy (1992)

4. A Gift for Murder (1992)

5. Murder by Mail (1993)

6. Once upon a Crime (1995)

7. Grave Choices (1995)

8. Flirting with Death (1996)

9. Midsummer Malice (1997)

10. Death Calls the Tune (1999)

Tue 12 Feb 2019

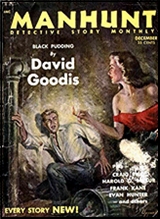

by Jeff Vorzimmer

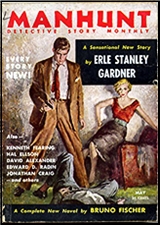

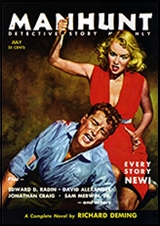

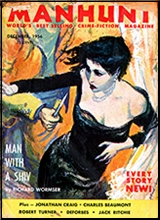

The first issue of Manhunt appeared on newsstands in late 1952 and within two years became the widely acknowledged successor to Black Mask, which had ceased publication the year before. The stories in Manhunt captured the noir of Cold War angst like no other fiction magazine of its time and paved the way for television anthology shows such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

Manhunt can best be described as a joint venture between publisher Archer St. John and literary agent Scott Meredith, both based in New York. In 1952, St. John published comic books and had recently ventured into and, in fact, developed 3D comics and graphic novels. His company, St. John Publishing, produced what is considered the first graphic novel, It Rhymes with Lust, in 1950, which was part crime, part romance, and followed that up later the same year with The Case of the Winking Buddha. Neither book sold very well and the line, dubbed “Pictures Novels,†was discontinued after the second title.

Archer St. John, always an admirer of Black Mask magazine, the premier pulp magazine from the 1920s through the 40s, felt that since that magazine’s demise there was a void in the world of crime-fiction magazines and an opportunity. Of course, comic book publishers don’t usually have big editorial staffs nor do they solicit manuscript submissions. For that, St. John approached Scott Meredith, a literary agent who was beginning to turn the publishing world on its ear with practices such as charging would-be writers reading fees and submitting manuscripts to publishers simultaneously, creating an auction system of competing bids.

For Scott Meredith it was an opportunity to get his stable of writers in print and create another stream of income. St. John served as the front man to avoid any ethical questions or conflict of interest charges that Meredith might otherwise face. St. John would manage the production of the magazine from layout and illustration to the printing and distribution of the magazine while Meredith’s office would supply a steady supply of fiction and editing.

Of course, it was not a very well-kept secret within the publishing business. Those in the business, with even a passing familiarity with the roster of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, would notice a preponderance of his clients on the pages of Manhunt. In fact, all ten of the most prolific contributors to the magazine were Meredith authors who, between them, contributed over one-fifth of all stories that appeared in Manhunt over the course of its fourteen-year run.

Manhunt has often been referred to, then and now, as a closed shop, only available to the Meredith stable of authors, but that’s not entirely true. As often as not, writers not represented by an agent would submit stories directly to Manhunt. These were forwarded to the Meredith office and occasionally published in the magazine, though the authors were not usually signed to a publishing contract on the strength of a single story.

This would sometimes create awkward moments when a producer from a television studio such as Revue, producers of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and M Squad, would call up the agency looking to secure the rights to a story they read in Manhunt. The Meredith agent would stall the producer, scramble to locate and sign the author, then make the deal.

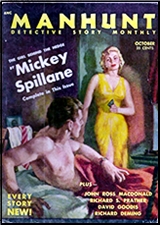

Archer St. John originally wanted to call the magazine Mickey Spillane’s Mystery Magazine to compete with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, albeit with grittier, more hard-boiled stories. Having Spillane’s name on the masthead would have been appealing to both St. John and Meredith in that, by 1952, Spillane’s first six books had combined sales of 20 million copies. His first book, I, The Jury had sold 3.5 million copies by 1953, when it was adapted for the screen.

When Scott Meredith checked Spillane’s contract with his publisher, Dutton, he found a clause that gave the publisher total control of Mickey Spillane’s name in conjunction with any books or periodicals. If they were to use Spillane’s name on the magazine they had to get Dutton’s permission. However, Dutton balked at the idea.

Dutton felt that short stories were a distraction for Spillane, and they wanted him to get back to the business of writing novels. At that point, it had been over a year since Spillane had delivered his last novel to them (and it would be ten years before he delivered his next one). The name of the magazine was changed to Manhunt, a named borrowed from a then-defunct crime comic book.

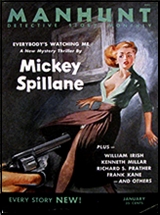

St. John intended to kick off the magazine with a Mickey Spillane story. He had heard that Collier’s Magazine had turned down a novella Spillane had written, “Everybody’s Watching Me,†and offered to serialize the novella in the first four issues of the new magazine and pay Spillane $25,000 (equivalent to $237,000 today). If Spillane’s name could not be on the masthead, it would at least be on the cover of the first four issues.

The print run of the first issue, dated January 1953, was 600,000 copies and sold out in five days. It was digest size (5½”x7½”), 144 pages and priced at 35¢ and $4 for a year’s subscription. In addition to the lead story by Spillane, the issue also included stories by Cornell Woolrich under the name of William Irish; Ross Macdonald, under his real name, Kenneth Millar; and Evan Hunter, later known by the pen name Ed McBain.

It also included a story featuring Richard Prather’s detective Shell Scott, featured in six novels of his own over the previous three years, and, who rivaled Spillane’s Mike Hammer in popularity, and another featuring Frank Kane’s Johnny Liddell. Stories by Floyd Mahannah, Charles Beckman, Jr. and Sam Cobb (Stanley L. Colbert) rounded out the issue.

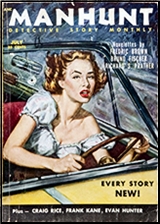

St. John had his favorite artist, Matt Baker, a black man in the predominantly white world of comic book illustration, do the artwork for Manhunt. Baker was the artist who had done the panels for the first of the two graphic novels St. John had published, but brought an entirely new look to the Manhunt illustrations, heavy ink and each highlighted with a different spot color. Each story had one illustration on the first page in a style not unlike Manhunt.

Baker himself would do most of the illustrations for the first nine issues, thereby setting the style used for the entire 15-year run. Up-and-coming young artists such as Robert McGinnis, Walter Popp and Robert Maguire, as well as older, more established artists, such as Frank Uppwall and Willard Downes, painted the covers.

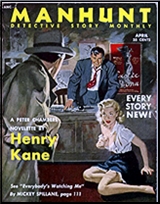

The editorial note on the contents page of the second issue stated that the press run of the first issue probably should have been closer to a million copies. St. John apparently split the difference and ran 800,000 copies of the second issue. In addition to the second installment of “Everybody’s Watching Me,†the lead story was another by Kenneth Millar, a Lew Archer story titled “The Imaginary Blonde†under his new pseudonym John Ross Macdonald.

There were also two more stories by Evan Hunter under the pseudonyms Richard Marsten and Hunt Collins, a Paul Pine story by John Evans, as well as stories by Jonathan Craig (Frank E. Smith), Fletcher Flora, Richard Deming, Eleazar Lipsky and Michael Fessier.

In addition to the contributors of the first two issues, the third issue was notable in that it included stories by older, more established writers such as Leslie Charteris with a Saint story, Craig Rice (Georgiana Craig) with a John J. Malone story, as well as stories by William Lindsay Gresham and Bruno Fischer.

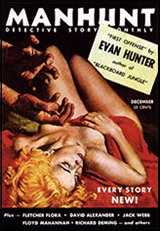

The third issue also contained another two stories by Evan Hunter, one under the pseudonym Richard Marsten. In fact, Evan Hunter contributed 16 stories to the first 9 issues of Manhunt under his own name and various pseudonyms and 48 stories over the entire life of the magazine, making him the most prolific contributor by far. For a magazine that was supposed to be all about Mickey Spillane, it was turning out to be about Evan Hunter.

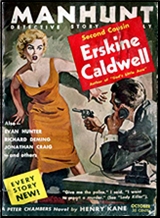

By mid-1953, St. John, with Meredith’s help, started a campaign to lure big name authors to Manhunt. They approached James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, Rex Stout, Erle Stanley Gardner, Nelson Algren and Erskine Caldwell. They offered as much as $5,000 (about $47,000 today) for a 5,000-word story. This was the kind of money writers could expect from the slick magazines, but not from the pulps.

Many writers like Erle Stanley Gardner initially balked at the idea of publishing in Manhunt, but eventually succumbed. Gardner’s first response to his agent was, “I hate to turn down an offer of $5000 for a story, but, confidentially, I don’t like this magazine concept with which Manhunt started out. I think it is a definite menace to legitimate mystery fiction.â€

By the end of the decade all the big-name writers, including Gardner, had agreed to publish stories in Manhunt, though many appeared only once, the last being the only appearance by Raymond Chandler. His story, “Wrong Pigeon,†previously published only in England, appeared in the February 1960 issue.

The year 1953 would be the peak year for St. John Publications. Manhunt was turning out to be one of its biggest-selling titles, spawning spin-off titles Verdict and Menace, and its 3D comics were selling millions of copies. The company had 35 different comic book titles with several lines of romance comics, Mighty Mouse and Three Stooges comic book lines, for a total of 169 issues published that year.

Another of Archer St. John’s projects was a man’s magazine that would include articles of interest to men, photos of women in various stages of undress and quality fiction. However, he was concerned about the post office not allowing the mailing of what they would certainly deem pornographic material to subscribers. After Playboy appeared in December 1953, he was emboldened to move ahead with the project.

In 1954, Archer brought in his 24-year-old son Michael to help run the business, while he focused on the new men’s magazine, Nugget. Again, he turned to his favorite artist, Matt Baker, to do the illustrations in the magazine. Although that year would turn out to be another good year for St. John Publications, there was trouble on the horizon.

In the spring of 1954, there was a backlash against violence in comic books that were clearly aimed at children. The crusade was led by New York psychiatrist Fredric Wertham who published the now-infamous Seduction of the Innocent, a book-length study of the adverse effects of violent comic books on young minds, and led to a Senate investigation, which issued its own Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency Interim Report that included a list of comic book titles it deemed inappropriate for children. There were, of course, some St. John titles on the list.

It was also apparent in early 1954 that 3D comics were just a passing fad. Sales of 3D comics plummeted to the point that, by March of 1954, 3D titles had all but disappeared. The sales of comic books in general were in a slump, brought on in large part by the scare created by politicians and PTA groups after the Wertham study.

Other forces were coming to bear that would have a personal effect on Archer St. John and the fate of St. John Publications. In August of 1954, President Eisenhower signed The Communist Control Act, which outlawed the Communist Party in the United States. Anyone who had ever been a member of the Communist Party could face imprisonment or even the revocation of citizenship.

Archer’s brother, the famous journalist Robert St. John, living a self-imposed exile in Switzerland and doing research for books on South Africa and Israel, was determined by the FBI to have been a member of the Communist Party. On September 24, 1954, Robert St. John was summoned to the American Consulate in Geneva and stripped of his passport. When Robert asked why his passport was being taken from him, the reply from the Consul-General was that it was because of his Communist Party activity.

Robert turned to his brother Archer back in the States for help to get his passport reinstated and the necessary affidavits for the appeal. Over the following months Archer, who was very close to his brother Robert, became increasingly frustrated by the stonewalling he got from the U.S. government on his brother’s case.

Adding to his personal turmoil was the fact Archer was separated from his wife and living at the New York Athletic Club. His employees at St. John Publications also suspected he was addicted to amphetamines in addition to being an alcoholic. By mid-1955 Robert’s case had still not been decided, though he had submitted numerous affidavits from noted citizens that affirmed that he was never a member of the Communist Party.

In August, Archer told family members that he was being blackmailed, but didn’t give anyone any details. His son Michael told him not to give in to the blackmailers. Archer told his son that he was staying at the apartment of a friend but wouldn’t tell Michael where.

On Friday night August 12, 1955, Robert St. John got a call in Switzerland from Archer in New York who told him, “Never in my life have I felt so frustrated. I feel like I’m banging my head against a stone wall. I see no possibility of my getting your passport back. I’ve done everything in my power to help you, but I’ve failed. I’m sick over this.†The next morning Robert got a call telling him that his brother had overdosed on sleeping pills, an apparent suicide. He was 54 years old.

At times, Archer St. John’s life resembled a story from the pages of Manhunt — Al Capone’s gang once kidnapped him when he was young newspaper publisher — and his death was no different. The apartment where Archer had been staying was a duplex penthouse owned by an attractive, redheaded former model and divorcee named Frances Stratford. She had been sleeping in an upstairs bedroom and had found Archer downstairs lying next to the couch, unresponsive, at 11:30 a.m. that Saturday morning.

A couple had been seen leaving the apartment the night before, and the police were investigating. On Monday, the New York Daily News reported, “A couple of shadowy West Side characters, a man and a woman, suspected of feeding dope pills to magazine publisher Archer St. John, were being hunted … by detectives investigating St. John’s mysterious death in the penthouse apartment of a former Powers model.â€

After St. John’s death, his wife, Gertrude-Faye, known as “G-F†or “Geff,†showed up at the offices of St. John Publications and promptly fired the entire staff, including Matt Baker. Apparently, she hadn’t wanted anyone around who knew about her husband’s affairs. The irony was that none of the staff knew anything about St. John’s private love life, not even Baker who was probably as close to him as anybody.

Despite the failure of the previous Manhunt clones, Verdict, which lasted only four issues in late 1953 and Menace, which lasted two issues, the following year, Michael St. John decided to expand his own editorial staff and to introduce yet two more titles, Mantrap and Murder! in 1956. Unfortunately, the new titles suffered from the same lackluster sales of the first two spin-off titles and were discontinued just as quickly.

Undaunted by the failure of four new titles in as many years, Michael kept searching for a formula that would repeat the success of Manhunt. What Michael and his business manager, Richard Decker, came up with was an opposite, more genteel, direction. They approached Alfred Hitchcock with an offer to license his name and image for a mystery digest.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine was an immediate success and, in fact, sales would steadily increase throughout the rest of the decade while those of Manhunt were in steady decline, down to 169,000 by 1957. Its digest size, with two-column layout and heavily inked spot color illustrations, were identical to Manhunt’s.

In an effort to boost sales of both Manhunt and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, St. John and Decker decided to increase the size of both magazines from their current digest size to regular magazine size to get, what they hoped would be, more attention on newsstands. What it got Manhunt was the unwanted attention of the Federal District Attorney.

After only the second issue at the bigger magazine size, Michael St. John, Richard E. Decker, Charles W. Adams (the Art Director) and Flying Eagle Publications (a subsidiary of St. John’s Publications and holding company of Manhunt) were indicted on March 14, 1957, for “mailing or delivery copies of the April, 1957, issue of a publication entitled Manhunt containing obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy or indecent matter†in violation of United States Penal Code 18 U.S.C. §1461.

In District Court in Concord, New Hampshire, St. John’s lawyers moved to have the charges dismissed on the grounds that the complaint didn’t identify what article was specifically being charged in the issue as “obscene, lewd, filthy or indecent.†They argued that “the indictment is so loosely drawn that it would not afford them protection from further prosecution.†District Court Judge Aloysius J. Connor agreed and threw out the indictments on August 7, 1957.

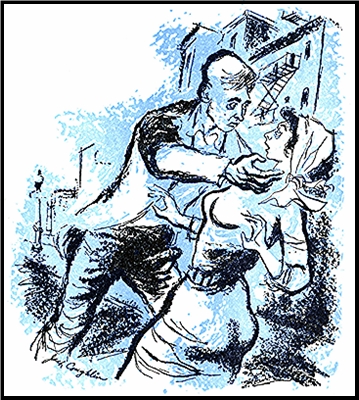

Federal prosecutors promptly refiled charges with specific complaints: “All six of the stories have definitely weird overtones and can certainly be characterized as crude, course, vulgar, and on the whole disgusting. But tested by the reaction of the community as a whole — the average member of society — it seems to us that only the feature novelette, ‘Body on a White Carpet,’ and the illustration appearing on page 25 accompanying the story entitled ‘Object of Desire,’ could be found to fall within the ban of the statute as limited in its application by the important public interest in a free press protected in the First Amendment.†The defendants faced a fine of $5,000 ($43,000 in today’s dollars) and up to five years in prison.

“Object of Desire†on page 25 of the April 1957 issue.

On December 1, 1958, the final verdict of the District Court jury was that Flying Eagle Publications and Michael St. John were guilty and fined $3,000 ($26,000 today). Judge Connor gave St. John a separate fine of $1000, a suspended sentence of six months in jail and two-year probation. Richard E. Decker and Charles W. Adams were acquitted. Michael St. John immediately appealed the verdict and the case went to Federal Appeals Court.

On January 21, 1960, the Federal Appeals Court in Boston set aside the verdict of the District Court and ordered a new trial. Chief Judge Peter Woodbury found that the prosecutors had erred in their instructions to the jury by telling them that two defendants, Decker and Adams, originally listed on the indictment had “been separated from this action†rather than that they were acquitted.

A year later the Court of Appeals upheld the decision of the Circuit Court on January 10, 1961, and Judge Bailey Aldrich upheld the original fine of $5,000. After three years and nine months of litigation, St. John Publishing was financially drained. The circulation of Manhunt had dropped to 100,000, and Richard Decker had split with St. John in the summer of 1960, taking Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine with him to Palm Beach, Florida.

Scott Meredith had always been annoyed with what seemed to be chronic cash-flow problems at St. John, and it only got worse. The magazine limped along for the next six years, and fewer of Meredith’s writers appeared in the magazine. Only 33 stories by the top ten Meredith contributors appeared in the 1960s.

Only three Evan Hunter stories appeared in Manhunt in the 60s, the last story, fittingly, in the last issue of April/May 1967. By then the circulation had dropped to a little over 74,000 copies. Michael St. John decided to get out of the publishing business entirely and sold off all the assets of St John Publishing, including Nugget.

Sources:

Aldrich, Baily, Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals, Flying Eagle Publications v. United States, 285 F.2d 307, January 10, 1961

Ashley, Michael, author, Kemp, Earl and Ortiz, Luiz editors, Cult Magazines A-Z: A Curious Compendium of Culturally Obsessive & Curiously Expressive Publications, 2009, Nonstop Press

Benson, John, Confessions, Romances, Secrets, and Temptations: Archer St. John and the St. John Romance Comics, 2007, Fantagraphics Books

Benson, John, Romance Without Tears, 2003, Fantagraphics Books

Fugate, Francis L. and Roberta B., Secrets of the World’s Best-Selling Writer, 1980, William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Carlson, Michael, “Interview with Mickey Spillane,” Crime Time website, June 29, 2002

Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, July 8, 1925, pg. 16

Collins, Max Allan and Traylor, James L, Spillane (to be published in 2020)

Cook, Michael L., Monthly Murders: A Checklist and Chronological Listing of Fiction in the Digest-Size Mystery Magazines in the United States and England, 1982

Horowitz, Terry Fred, Merchant of Words: The Life of Robert St. John, 2014, Rowman & Littlefield

Meredith, Scott and Meredith, Sidney, The Best From Manhunt, 1958, Perma-Books

Morgan, Hal and Symmes, Dan, Amazing 3-D, 1982, Little, Brown and Company

Morrison, Henry, Literary Agent and former Scott Meredith Literary Agency employee (1957-1964), Interview, January 29, 2019

Nashua Telegraph, Nashua, NH, January 22, 1960, pg. 2

Nashua Telegraph, Nashua, NH, January 11, 1961, pg. 2

New York Daily News, New York, NY, August 15, 1955, pg. C5

N. W. Ayers & Sons Directory of Newspapers and Periodicals, 1954-1967

The Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa, Canada, March 2, 1957, pg. 2

The Portsmouth Herald, Portsmouth, NH, March 15, 1957, pg. 7

The Portsmouth Herald, Portsmouth, NH, December 2, 1958, pg. 8

Quattro, Ken, Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could, 2006, www.comicartville.com

Waller, Drake, It Rhymes with Lust, 1950, 2007, Dark Horse Books

Woodbury, Peter, Chief Judge, United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit, Flying Eagle Publications v. United States, 273 F.2d 799, January 21, 1960

Tue 12 Feb 2019

SF Stories I’m Reading: GORDON EKLUND “Underbelly.”

Posted by Steve under Science Fiction & Fantasy , Stories I'm Reading[4] Comments

LESTER del REY, Editor – Best Science Fiction Stories of the Year: Second Annual Edition. E. P. Dutton, hardcover. 1973. Ace, paperback, December 1975.

#3. GORDON EKLUND “Underbelly.” Short story. First published in Worlds of If, September-October, 1972. First collected in Retro Man: Selected Stories, Volume Two (Ramble House, trade paperback, 2016).

Author Gordon Eklund broke into the the ranks of professional science fiction writers in a big way. From his Wikipedia page:

Between 1971 and 1980 he had some 16 novels published, then except for one novel in 1989, he and his writing virtually disappeared from view. I really shouldn’t speculate in print, but in cases such as this, it is often that contracts dried up and/or he decided to keep his day job.

As for “Underbelly,” it reads like the first chapter of a much longer book. Why Gabriel Solar, living in an vaguely established post-apocalyptic village, is chosen to be the subject of a b experiment designed to enhance the physical powers of living beings conducted by two scientists with two differing approaches, working in a well-guarded compound nearby is only partially referred to.

Even less clear is what will happen to Gabriel once he’s been given the gift of physical perfection. Can he return to his home where he’s now superior to everyone, making the rest of his life a very uncertain one?

Which of course is the point. I’d like to read the rest of the story, though — the part that follows this one. My first reaction was that it could have been a lot more interesting than the snippet we’re given here — but then again perhaps not. Thinking about it later, I decided that just maybe what Eklund gives us in “Underbelly” is all we need, allowing us to fill out the rest of the story on our own.

Conclusion: While not perfect by any means, this is a better story than I thought it was when I first read it.

—

Previously from the del Rey anthology: ROBERT SILVERBERG “When We Went to See the End of the World.â€

Mon 11 Feb 2019

A Book! Movie!! Review by Dan Stumpf: DOROTHY B. HUGHES The Fallen Sparrow / (1943)

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[4] Comments

DOROTHY B. HUGHES – The Fallen Sparrow. Duell, Sloan & Pearce, hardcover, 1942. Paperback editions include: Dell #31, mapback edition, 1943 or 1944; Bantam, 1970/1979; Carroll & Graf, 1988.

THE FALLEN SPARROW. RKO, 1943. John Garfield, Maureen O’Hara, Walter Slezak, Patricia Morison, John Banner, John Miljan, Hugh Beaumont. Screenplay by Warren Duff. Directed by Richard Wallace.

I’ve long been impressed by Dorothy B. Hughes’ ability to put the reader into the head of her protagonists while writing in the third person. In a Lonely Place featured a murderous sociopath; here it’s a paranoid who really is being persecuted, but in both cases we follow a narrative in which we’re not always quite sure of what is actually happening to the central character . Or if we can trust that he’s reading it right

Sparrow opens two years before the story proper starts. Kit McKitrick, young, rich and idealistic, joined the International Brigade to fight Facism in Spain. As things fell apart he snatched some valuable relics from a looter, then spent two year in a prison cell being tortured to give up their whereabouts. His most vivid memory of that time is the periodic visits of a man he never saw… a limping man from Berlin, whose arrival always brought on new and more painful torment.

Then we switch to New York City in Wartime, with Kit returned to his Park Avenue crowd, thanks to an escape engineered (he thinks) by a longtime cop-pal who plunged to his death from a window while Kit was recuperating out West. The papers say it was accident or suicide, Kit knows it was murder.

This forms the springboard for a perfectly crafted tale of murder and subversion among the Smart Set, as Kit’s mission of detection becomes a journey of discovery that uncovers some troubling truths about the people he once called friends – and about himself.

Hughes builds suspense with some clever twists: Kit starts hearing the limping man from Berlin here in New York — or does he? Then he learns that his captors engineered his “escape†from Spain as a ploy to get him to lead them to the relics. Or did they? And suddenly, in his mind (and ours?) he is as much hunter as hunted.

When RKO filmed this the next year they wisely did it in early-noir style, with a few nods to The Maltese Falcon (1941) spiced up with expressionist lighting and oppressive camera angles. This being wartime, there are a couple of patriotic speeches about Why We Fight, but by and large the emphasis is on McKitrcick’s fragile sanity.

Producer Robert Fellows (Hondo, The Screaming Mimi, Ring of Fear, etc.) casts this perfectly, with a trio of femmes fatales that includes Maureen O’Hara (icily coiffed and made up in an Audrey Totter look) Patricia Morision and Martha O’Driscoll. John Banner, Erford Gage and Hugh Beaumont skulk around nicely in the background under the sinister supervision of Walter Slezak as a wheelchair-bound (or is he?) aristocrat with an interest in torture and the Borgias, chewing the scenery with voracious relish.

And best of all, there’s John Garfield, that edgiest of leading men, as the half-crazy hero of the piece. Nobody could convey angst like Garfield, and he sinks into the role wonderfully, veering from manic energy to desperation with a tic of the cheek. He even seems to sweat on cue!

Scenarist Warren Duff (who produced Out of the Past) streamlines Hughes’ book quite well, shortcutting past some of the novel’s digressions and wisely letting the actors convey their characters’ complexities. The result is a film that brings the book to life and makes it pure Cinema — and a fun movie to watch.

Mon 11 Feb 2019

Music I’m Listening To: LONE JUSTICE “You Are the Light.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[6] Comments

Lone Justice was a country rock band formed in 1982 featuring lead singer Maria McKee, who later went on to a solo career. “You Are the Light” is a song on their self-titled debut album, which was released in 1985.

Sun 10 Feb 2019

Books Noted: News from STARK HOUSE PRESS.

Posted by Steve under Books Noted , Publishers[7] Comments

I’ve asked Greg Shepard, publisher and editor-in-chief at Stark House Press, to tell us what’s come out from them recently or what will be showing up soon. He has most graciously agreed:

by Greg Shepard

This year Stark House Press will celebrate being in business for 20 years. Our first book was a hardback collection of fantasy stories by Storm Constantine. We followed that with a few more Constantine projects, then jumped into Algernon Blackwood territory, a supernatural sidestep on our way to crime.

Twenty years in the publishing business has brought us full circle; in January, 2019, we published the definitive biography of Algernon Blackwood by Mike Ashley — The Starlight Man. This is not only the first paperback edition, but also the most complete version, since Ashley added back in all the bits his UK hardback publisher asked him to take out back in 2001, with lots of new pictures as well.

Although our primary focus has mainly been “men’s†hardboiled, noir fiction of the 40s to the 60s — our lead title for January was Lead With Your Left and The Best That Ever Did It by Ed Lacy, two gritty, New York cop mysteries — we recently began adding more of the women’s suspense authors from that era, too. In November of 2018 we issued End of the Line by Bert & Dolores Hitchens as part of our Black Gat series. This is one of five railroad mysteries that Dolores wrote with her rail-detective husband, Bert. But Dolores also wrote a lot of fine standalone mysteries during the 1950s, and we will be bring six of those back over the next couple years, starting with Stairway to an Empty Room and Terror Lurks in the Darkness next fall.

In February, we will be proudly publishing two novels by the incomparable Jean Potts. She won the Edgar Award for one them, Go, Lovely Rose, and was nominated for the other one, The Evil Wish. Both are excellent novels of psychological suspense, the first story dealing with the murder of a woman whom everyone in town hates, the second concerning a murder that is planned but not executed, leaving distrust and suspicion in its wake. Booklist has already labeled these “two masterpieces†and we’re excited to be bringing them back, with more to come.

Stark House will also be reprinting the works of Bernice Carey and Helen Nielsen. Back in November of 2016 we reprinted Woman on the Roof by Nielsen, and in May we have two more of her clever Southern California mysteries to offer: Borrow the Night and The Fifth Caller. Also in May we will be publishing (for the first time in paperback) Carey’s The Man Who Got Away With It and The Three Widows. Carey set her novels in small town California where she lived, often peppering them with her own brand of social justice. As Curtis Evans says in his introduction, “the most significant contribution of Bernice Carey to mid-century crime fiction was her commitment to exploring realistic social conditions in her novels.” She also created some very interesting characters.

Over in the noir camp is one of my personal favorites, Gil Brewer. We published two of his noir thrillers, The Red Scarf and A Killer is Loose, back in October. Brewer was the master of momentum. He’d create a desperate situation for this protagonist—usually involving lots of cash and a young, willing woman — and turn him loose to frantically pursue each with equal amounts of sweat and lust.

This year, we are reprinting Redheads Die Quickly, the definitive collection of Brewer stories edited by David Rachels back in 2012, with five new ones added. And later this year we will be complementing this volume with two new Brewer collections: Death is a Private Eye, set for August, and Die Once — Die Twice, tentatively scheduled for early 2020; each volume edited and introduced by David Rachels.

In March, Stark House is following up its Carter Brown program with three more Al Wheeler mysteries: No Law Against Angels, Doll for the Big House and Chorine Makes a Killing. If you don’t recognize these titles, that’s because No Law was published here as The Body (the very first Brown book to be published in the U.S.) and Doll as The Bombshell.

Back in the late 1950s, when Brown’s Australian publisher started to populate the world with his books, the feeling was that they needed Americanizing. So these first few Wheeler stories were revised for the U.S. audience. I thought it’d be more fun to reprint the original Australian versions, so that’s what we’re doing. In fact, Chorine has never been published in the U.S. at all, so that’s a first for most American readers.

Those are just a few of the highlights. There’s more: Jeff Vorzimmer has edited the mammoth The Best of Manhunt and will be discussing it in a separate post. That’s our big summer title, set for July. I am also working on a second trio of Lion Book noirs, another two-fer of Barry N. Malzberg satires (The Spread and The Social Worker), our final Peter Rabe volume (New Man in the House and Her High School Lover), plus lots of odds and ends over at Black Gat Books, including authors like Noël Calef, Ovid Demaris, Fredric Brown and Louis Malley.

Sun 10 Feb 2019

A Mystery Movie Review: MURDER AT 3 AM (1953).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[2] Comments

MURDER AT 3 AM Renown Pictures, UK, 1953; Ellis Films, US, 1955. Dennis Price (Inspector Peter Lawton), Peggy Evans, Rex Garner, Philip Saville, Leonard Sharp. Director: Francis Searle.

Save for a trickle of recognition for Dennis Price, the leading man in this low budget British semi-thriller, the cast of Murder at 3 am was totally unknown to me. I think you may have had to be there — England in the early 1950s — for any of them to have made a lasting impression on you.

Not that they didn’t do a professional job of ii. The budget may have been small and the story riddled with clichés, but there’s nothing in this film that you can lay any criticism of the cast to.

The last of a series of robberies of well-to-do women, their money and jewelry stolen from them at the doorsteps as they arrive home at night, has ended in the death of one of them, putting a lot of pressure on Scotland Yard in general and Inspector Peter Lawton in particular.

What the robberies have had in common is that they all took place at 3 am, and the women were all coming home alone in cabs from various night clubs in the area. What the new fiancé of the inspector’s sister, a budding mystery writer, discovers, however, is that the first letters of the names of the night clubs spell out P-L-A-Y-…, which suggests where the killer may strike next.

We are traipsing on Agatha Christie and Ellery Queen territory here. Unfortunately additional clues start pointing to the fiancé himself as the one responsible for the crimes. I spoke of clichés up there earlier. The denouement is one of the oldest in the books.

But what can I tell you? I both noted the limitations of the story and then ignored them, and I enjoyed the movie anyway.