Search Results for 'chinese parrot'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 25 Feb 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY MARYELL CLEARY:

EARL DERR BIGGERS – The Chinese Parrot. Charlie Chan #2. Bobbs Merrill, hardcover, 1926. Reprinted many time, both in hardcover and paperback. Film: TCF, 1934, as Charlie Chan’s Courage,

The Charlie Chan stories are classics of detective fiction. However, classics of the past are not always to be read with enjoyment in the present. I reread The Chinese Parrot to see how well it holds its own with modern mysteries. My verdict is that it does so very well.

The many details which are of its own time add to the interest rather than detracting from it: the use of the telegraph, the “flivvers,” the ubiquitous Chinese “boys” as servants. The story is one of murder — surmised rather than known, an atmosphere of something wrong rather than a crime to be unraveled.

It progresses as theory after theory put forth by young Bob Eden is proven wrong by Charlie Chan’s detective work. It is most unbelievable when Bob continues to bend to Charlie’s plea not to hand over the pearl necklace which he is supposed to deliver.

Evidence of anything wrong at the Madden ranch is slim indeed; I have trouble believing that any impatient young man would procrastinate so on only the word of a Hawaiian detective he has never known before.

However, it is necessary to the story that he delay, so delay he does.And delay at last brings the story to a smashing conclusion. Dated? Yes, of course. Outdated? Never.

– Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Volume 4, Number 5/6 (December 1981).

Tue 9 Feb 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

REVIEWED BY MARYELL CLEARY:

EARL DERR BIGGERS – The Chinese Parrot. Charlie Chan #2. Bobbs Merrill, hardcover, 1926. Pocket #168, paperback; 1st printing, July 1942. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and paperback.

The Charlie Chan stories are classics of detective fiction. However, classics of the past are not always to be read with enjoyment in the present. I reread The Chinese Parrot to see how well it holds its own with modern mysteries. My verdict is that it does so very well. The many details which are of its own time add to the interest rather than detracting from it: the use of the telegraph, the “flivvers,” the ubiquitous Chinese “boys” as servants.

The story is one of murder surmised rather than known, an atmosphere of something wrong rather than a crime to be unraveled. It progresses as theory after theory put forth by young Bob Eden is proven wrong by Charlie Chan’s detective work.

It is most unbelievable when Bob continues to bend to Charlie’s plea not to hand over the pearl necklace which he is supposed to deliver. Evidence of anything wrong at the Madden ranch is slim indeed; I have trouble believing that any impatient young man would procrastinate so on only the word of a Hawaiian detective he has never known before. However, it is necessary to the story that he delay, so delay he does.

And delay at last brings the story to a smashing conclusion. Dated? Yes, of course, Outdated? Never.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 4, Number 5/6 (December, 1981). Permission granted by publisher/editor Jeff Meyerson.

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: It has been a while since one of Maryell’s reviews has appeared on this blog. Since that is so, let me reprint the following, which I wrote as a followup note to the first of her reviews here. This is from November 19, 2009:

Maryell Cleary, who died in 2003, was an ordained minister of the Unitarian Universalist Church as well a voluminous reader and collector of detective fiction. I met her once while she was taking a trip by car through New England. She stopped here to look at my collection and to go through my duplicates, and of course we spent a long, wonderful afternoon talking about each of our favorite characters and authors.

Maryell was especially fond of mysteries in the Golden Age tradition. In fact, she had a letter in the same issue of The Poisoned Pen as the one above in which she protested mildly that fans of private eye novels had taken over the pages of recent issues! More coverage, she requested, of authors like Martha Grimes, Ruth Rendell, Patricia Moyes, Charlotte MacLeod, Robert Barnard, Marian Babson, Dorothy Simpson and P. D. James.

To that end she also wrote many reviews and articles herself for the mystery fanzines of 20 and 30 years ago, including the still late lamented Poisoned Pen, published for many years by Jeff Meyerson. I’ve conferred with Jeff, and we both agree that she would have liked her reviews to go on after her. They will appear here on a regular basis for some time to come — she wrote a lot of them!

Sun 16 Jan 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY J. F. NORRIS:

EARL DERR BIGGERS – The Chinese Parrot. Paperback reprint: Pocket #168, 1942. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and soft. Silent film: Jewel, 1927; Charlie Chan: Sojin. Sound film: TCF, 1934, as Charlie Chan’s Courage; Charlie Chan: Warner Oland.

All right let’s get the racist thing out of the way right now. The Chan books are not racist. (The books! I’m talking about, the books!) They are, in fact, ANTI-racist and anyone who reads The Chinese Parrot will clearly see that Biggers has no tolerance for the bigoted treatment of Chinese and the stereotyped depictions of pidgin speaking characters in fiction. Let me give you two examples:

1. When confronted by the ignorance of Captain Bliss, a police officer who wants to charge Chan (in his disguise as Ah Kim, a servant) with a stabbing murder, Chan quickly turns the interrogation around and asks the Captain to produce a motive, fingerprints and the murder weapon, in fact any real evidence, before even thinking about continuing his bullying questions.

2. In one of their many secret meetings Bob Eden asks Chan to deliver a message to Madden, Ah Kim’s boss. Knowing that he will have to use his comic servant pidgin speech Chan replies: “With your kind permission, I will alter that message slightly, losing the word very. In memory of old times, there remains little I would not do […] , but by the bones of my honorable ancestors I will not say ‘velly.’ ”

OK? Enough said. Let’s move on, class.

If Dell’s mapback series had started up much earlier than 1943 or so the editors might have chosen Earl Derr Biggers’ books as some of the first mysteries to release in paperback. The inside blurb page for The Chinese Parrot, the second Charlie Chan novel, might read something like this:

What this book is about…

A $300,000 string of pearls, a parrot that speaks Chinese, a murder without a corpse, a missing antique Colt .45 revolver, an abandoned trolley car with a mysterious occupant, several buried cans, a ghost town in the hills.

This is a vastly entertaining, tightly plotted, and well written book. Instead of Hawaii, the action moves to the mainland. It opens in San Francisco then moves on to a Southern California desert town called El Dorado. Biggers has created some very American characters here and his gift for snappy dialogue makes the book all the more enjoyable.

Chan has a much larger role here and as mentioned above is undercover in the role of a Chinese “boy of all work” called Ah Kim who cooks, tends to fireplaces and even acts as chauffeur. He teams up with the son of a jeweler, Bob Eden, to uncover some obvious criminal doings at the home of P. J. Madden, a millionaire intent on buying the valuable pearl necklace.

The most baffling of the events is an apparent murder without a body. Tony, the African gray parrot of the title, is quite a mimic and in addition to spouting forth Chinese phrases he also squawks out, “Help! Help! Murder! Put down that gun!” Chan is convinced the bird was a witness to a murder.

Discovery of a missing antique gun with two chambers empty, and an attempt to hide a bullet hole in a wall by covering it with a painting, both support the theory of a murder having taken place in Madden’s home. But just who was killed and where did the body go?

Chan may have two white men as his aides in detection in this book, but it is he alone who will unmask the killer in a great finale where we see “his eyes blaze in anger” while covering the villains of the piece with two guns, one in each hand.. Truly, here is an excellent book not only in the series, but in all of early American detective fiction.

Even more striking is that this particular book seems to have been written only a few years ago. There is no sign of that quaint style that often makes a 1920s book unbearable to me. With the exception of only a few topical references tied to the period (the mention of United Cigar Stores, radio as a form of “miracle technology,” a scene where movie actors start dancing the Charleston like maniacs on speed, for example) the story seems to be occurring in the not too distant past rather than the late 1920s.

There is a movie location scout who talks about the motion picture industry as if it were now and not part of the silent era. There is a real estate agent trying his darndest to sell building lots in a developmental desert community called Date City. He spends his time tending to a feebly spurting fountain outside the gates hoping to lure “easy marks, uh rather, good prospects” into believing they’ll have a lovely new home and a rich life in what is now nothing but barren wasteland.

And there is Biggers’ masterful handling of lively dialogue only occasionally peppered with period slang that makes this a thoroughly engaging and surprisingly modern read for something written 85 years ago.

I read The House without a Key, the very first Chan book, last year and was also struck but its modern feel and its compassionate treatment of minority characters. I am now determined to read the remaining four books in the series.

I’ve repeatedly found the Charlie Chan books in my book hunting and buying binges and have owned at least one copy of each title over time. Because I found them to be great sellers in the past I began buying them with the express purpose of making a little cash by reselling them on-line.

Now with relatively affordable reprint editions from Academy Chicago at $14.95 a pop (with nifty period style cover art) I guess no one will want the older editions unless they come with the rare dust jackets. I’m glad to hang on to the four old Charlie Chan Grosset & Dunlap reprints and the one battered first edition I own of The House without a Key. I’m a new Chan fan for life and I’ll treasure the copies I was lucky enough to find.

SIDE NOTE:

For a fascinating read, find a copy of the recently published non-fiction work Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective & His Rendezvous with American History by Yunte Huang.

It’s a combination of a biography, critical essay, and sociological study of the Asian American in popular fiction and movies. Primarily a biography of Chang Apana — a Honolulu policeman who served as the inspiration for Charlie Chan — the book also gives insights into the life of Biggers, all of the Chan books and many of the Chan movies.

The similarities to Chan in the early books and Apana’s real life prior to his being a police officer are uncanny considering that Biggers had only heard mention of Apana and had never met or talked to him until 1930 or so.

Previously on this blog —

The Keeper of the Keys (reviewed by Marv Lachman).

Castle in the Desert (a film review by Dan Stumpf).

Mon 27 Mar 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

EARL DERR BIGGERS – Behind That Curtain. Charlie Chan #3. Bobbs-Merrill, hardcover, 1928. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback. Films: Fox, 1929; Fox, 1932, as Charlie Chan’s Chance.

This one begins almost immediately after the previous book in the series ended (The Chinese Parrot, 1926). It finds Sergeant Chan of the Honolulu Police still in San Francisco after aiding the police there conclude a case they needed his assistance for. Charlie is anxious to get back home again, as he is about to become a father again – for the eleventh time.

But as things happen in detective mysteries such as this one, fate conspires against him, and he finds himself caught up in helping solve the murder of a retired Scotland Yard detective at a dinner party at which both he and Charlie were honored guests. Although retired, as it turns out, the dead man was still working on a case he had never solved – that of a young married woman who had completely and mysteriously disappeared after a picnic party in faraway India many years earlier.

Was he closing in on a solution? Apparently so, and he had also apparently baited a trap for someone whose secret that person did not want revealed.

There is no shortage of suspects, including a world famous explorer, any number of female characters,, one of whom may even be the missing woman, and of course, a butler whose past he has managed to keep hidden until now. That all of these people have connections with Sir Frederic’s case is amazing but not (as it turns out) purely coincidental.

Working against a self-imposed deadline to return home, and confronted by a homicide detective who, quite naturally, resents any kind of assistance or other threat to his authority, Charlie works quietly and efficiently to bring all of the threads of the plot successfully together. Or at least so it appears: the plot is supremely complicated in a most exquisitely excellent fashion.

Add in a female assistant district attorney, almost unheard of at the time, a bit of 1920s romance, and a charming Chinese detective who continually speaks in the way of all the actors who ever played him in the movies did, and what you get is a Grade A novel that’s been the most fun I’ve had all year in reading.

___

NOTE: Biggers wrote only six Charlie Chan novels before his relatively early death. Later on, two other authors have added two more to the total:

Charlie Chan Returns, by Dennis Lynds (1974)

and

Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen, by Michael Avallone (1981)

I’ve owned both over the years, but have not read either. Has anyone?

Tue 17 Nov 2020

REVIEWED BY MIKE TOONEY:

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Summer 2020. Issue #54. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: Unusual Suspects.

The latest issue of OLD-TIME DETECTION (OTD) continues to maintain the high quality it has always enjoyed. Editor Arthur Vidro’s choices of material are, as usual, excellent; the world of classic detective fiction, long neglected, gets a new lease on life with every number.

Indeed, nothing says “classic detective fiction” like commentary from Edward D. Hoch, an expert on the subject as well as a shining example of how to write it. Vidro reproduces two introductions by Hoch to mystery story collections.

Ed Hoch’s fiction output is the envy of many writers, almost always matching quantity with quality. In his review of Crippen & Landru’s latest themed collection of Hoch’s stories, Hoch’s Ladies, Michael Dirda says it well: “His fair-play stories emphasize a clean, uncluttered narrative line, just a handful of characters, and solutions that are logical and satisfying. Each one sparks joy.”

Next we have a valuable history lesson by Dr. John Curran concerning the earliest periods of the genre, “‘landmark’ titles in the development of crime fiction between 1841 and the dawn, eighty years later, of the Golden Age,” especially as reflected in the publications of the Collins Crime Club.

Following Dr. Curran is a collection of perceptive reviews by Charles Shibuk of some pretty obscure crime fiction titles; for instance, have you ever heard of Brian Flynn’s The Orange Axe (“highly readable, steadily engrossing, well-plotted, and very deceptively clued”) or James Ronald’s Murder in the Family (“an absolute pleasure to read from first page to last”)?

Cornell Woolrich was definitely not ignored by Hollywood, as Francis M. Nevins shows us in his continuing series of articles about cinema adaptations. The year 1947 was a rich one for films derived from Woolrich’s works — Fall Guy, The Guilty, and Fear in the Night — but, as Nevins indicates, the quality of these movies is highly variable.

William Brittain is a detective fiction author who has been undeservedly “forgotten” of late, but a reprinting of one his stories (“The Second Sign in the Melon Patch”, EQMM, January 1969) shows why he should be remembered: “She wondered if anyone in Brackton held anything but the highest opinion of her would-be murderer.”

Charles Shibuk returns with concise reviews of (then) recently reprinted books by John Dickson Carr, Agatha Christie, Anthony Dekker, Ngaio Marsh, Ellery Queen, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Josephine Tey.

Dr. John Curran also returns. The world’s leading expert on Agatha Christie tips us off as to developments in Christieworld: a new short story collection, the closure of the long-running play The Mousetrap as well as the cancellation of the in-person Agatha Christie Festival and uncertainty about the release date for Kenneth Branagh’s version of Death on the Nile due to the beerbug, the publication of a new non-fiction book focusing on Hercule Poirot, and a radio play version of a previously unperformed non-criminous production by Dame Agatha dating from nearly a century ago.

This is followed by a collection of smart reviews by Jon L. Breen (The Glass Highway by Loren D. Estleman), Amnon Kabatchnik (The Man in the Shadows by Carroll John Daily), Les Blatt (The Chinese Parrot by Earl Derr Biggers), Ruth Ordivar (The World’s Fair Murders by John Ashenhurst), Arthur Vidro (The Kettle Mill Mystery by Inez Oellrichs), and Thor Dirravu (The Ten Faces of Cornell Woolrich, a collection).

Next we have Martin Edwards’s foreword to Joseph Goodrich’s collection of essays entitled Unusual Suspects (2020), which, Edwards is delighted to relate, “benefits from a quirky unpredictability and from being a mine of intriguing nuggets of information.”

Rounding out this issue are the readers’ reactions and a puzzle page, the latter a snap only if you’re thoroughly familiar with the life and career of Hercule Poirot.

Altogether this is a most satisfying issue of OLD-TIME DETECTION.

—

If you’re interested in subscribing: – Published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S.: $18.00 ($15.00 for Mensans). – One-year overseas: $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros).

Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal.

Mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743.

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net

Wed 26 Jan 2011

Posted by Steve under

General[6] Comments

J. F. “John” Norris, whose several posts and many comments you have seen here on this blog over the past couple of months, has begun his own, as of today, and he’s off to a great start. If you’re interested in classic detective fiction and other similar literature from the musty past, I highly recommend it to you — and even if you aren’t!

Going into more detail about it, he describes his blog as “a foray into the realm of the old-fashioned detective novel, the ghost story and supernatural novel of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, the pulp adventure magazines of the 30s & 40s and similar dusty relics.”

Along these lines John has already posted reviews of —

The Chinese Parrot – Earl Derr Biggers (1926)

The House of Strange Guests – Nicholas Brady (1932)

Murder on Wheels – Stuart Palmer (1932)

The Saltmarsh Murders – Gladys Mitchell (1932)

The Poison Fly Murder – Harriet Rutland (1940)

The Cut Direct – Alice Tilton (1938)

Death Turns the Tables – John Dickson Carr (1941)

…but between you and me, I don’t think he can keep up the pace. (He must have storing these up. That’s all I can think of.)

The full URL is http://prettysinister.blogspot.com/, and you can tell him I sent you.

Thu 26 Oct 2023

Posted by Steve under

General[9] Comments

From A Reader’s Guide to the American Novel of Detection (1993) by Marvin Lachman, and posted previously on the Rara Avis Internet group by Tony Baer:

The Shudders, Anthony Abbot

Charlie Chan Carries On, Earl Derr Biggers

Wilders Walk Away & Hardly a Man is still Alive, Herbert Brean

Triple crown, Jon Breen

The Junkyard Dog, Robert Campbell

Hag’s Nook, 3 coffins, crooked hinge, case of the constant suicides, Patrick butler for the defense, the burning court, John Dickson Carr

Kill Your darlings, Max Allan Collins

The James Joyce Murder & death in a Tenured Position, Amanda Cross

The Hands of Healing Murder, Barbara D’Amato

A Gentle Murderer, Dorothy Salisbury Davis

The Judas Window, The reader is Warned, The Gilded Man, She Died a lady, He wouldn’t Kill Patience & Fear is the same, Carter Dickson

Method in Madness & who Rides a Tiger, Doris miles Disney

Old Bones, Aaron Elkins

The horizontal Man, Helen Eustis

The case of the Howling Dog, …the counterfeit eye, ….lame canary, …perjured parrot, …crooked candle, …black eyed blonde, Erle stanley Gardner

What a Body!, Alan Green

The Leavenworth Case, Anna Katherine Green

The Bellamy trial, Frances Noyes Hart

The Devil in the Bush, Matthew head

The Fly on the Wall, Tony Hillerman

9 times 9, Rocket to the Morgue, H.H. Holmes

A Case of Need, Jeffery Hudson

Friday the Rabbi Slept Late, Saturday the Rabbi Went Hungry, Harry Kemelman

Obelists Fly High, C. Daly King

Emily Dickinson Is Dead, Jane Langton

Banking on Death, Accounting for Murder, Murder Makes the Wheels Go Rounds, Murder Against the Grain, When in Greece, Emma Lathen

The Norths Meet Murder, Murder Out of Turn, The Dishonest Murderer, Frances and Richard lockridge

Through a Glass Darkly, Helen mcCloy

Pick Your Victim, Pat McGerr

Rest You Merry, Charlotte MacLeod

Paperback thriller, Lynn Meyer

The Iron Gates, Ask For Me Tomorrow, vanish in an Instant, beast in View, Margaret Millar

Death in the Past, Richard Moore

Murder for Lunch, Haughton Murphy

The 120 Hour clock, Francis Nevins, Jr.

The body in the Belfrey, katherin Hall Page

The Puzzle of the Blue Banderilla, stuart Palmer

Remember to Kill Me, Hugh Pentecost

Generous Death & No Body, Nancy Pickard

Unorthodox Practices, Marissa Piesman

The roman Hat Mystery, the French Powder Mystery, The Greek Coffin Mystery, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, The Chinese Orange Mystery, Calamity town, Cat of Many Tails, Ellery Queen

Puzzle for Puppets, Parick Quentin

Death from a Top Hat, Clayton Rawson

The Gold gamble, Herbert resnicow

8 Faces at 3, Craig Rice

Strike Three You’re Dead, Richard Rosen

The Tragedy of X, The Tragedy of Y, Barnaby Ross

The Gray Flannel Shroud, Henry Slesar

Reverend Randollph and the wages of Sin, Charles Merrill Smith

Double Exposure, Jim Stinson

Carolina Skeletons, David Stout

Fer de Lance, The rubber band, too many cooks, some buried Caesar, the silent speaker, in the best families, the black mountain, the doorbell rang, a family affair, rex stout

Rim of the Pit, Hake Talbot

The Cut Direct, Alice Tilton

The Greene Murder Case, SS van Dine

Sun 22 May 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY JIM McCAHERY:

TIMOTHY FULLER – Three Thirds of a Ghost. Jupiter Jones #2. Little Brown, hardcover, 1941. Popular Library #81, paperback, [1946].

This is the second of the Jupiter Jones adventures It is somewhat of a relief to see a more mature sleuth than in the earlier Harvard Has a Homicide to which there is a reference in this present work as well as to Jupiter’s having been “an eccentric graduate student” who “interfered with the Cambridge Police.”

The scene this time is Boston. and Jupiter, who is now a recently appointed instructor in Fine Arts at Harvard, cooperates almost fully with the police after witnessing with some two hundred others, the shooting death of Pulitzer Prize author George Newbury during the latter’s talk at Bromfield’s Bookstore on the occasion of its 150th Anniversary.

The book purports to be an intimate and humorous roman a clef in miniature with Newbury representing John P. Marquand, social satirist and creator of a well-known Oriental detective (cf. Newbury’s Chinese detective “Parrot” and Marquand’s Japanese Mr. Moto). On this score, Timothy Fuller himself says in his author’s note: “Some of the characters in this book bear a singular resemblance to persons now living, not dead… Let us say that the resemblances are too close to be “coincidental and hope they are too inaccurate to be libelous.”

When Police Captain Hogan is killed during a sudden basement fire at the bookstore, Jones realizes that he had already found evidence sufficient to incriminate Newbury’s killer. Jupiter’s fiancee Betty Mahon, to whom he proposes in a cab, is naturally on hand throughout the book. The disappearance of the supposed murder weapon is cleverly manipulated as is the cat-and-mouse play between Jones and Newbury’s Oriental secretary, Lin.

It takes a bogus seance and a full ghost in the person of Jupiter Jones to trap the killer in an interesting denouement which, with apologies to Van Dine, is very well handled. The few red herrings were quite enough to distract my attention from the real killer. Lighthearted and unpretentious fun.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 2, Number 5 (Sept-Oct 1979).

Thu 5 Sep 2013

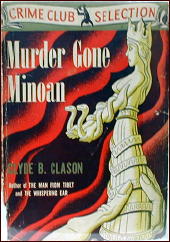

CLYDE B. CLASON – Murder Gone Minoan. Rue Morgue Press, trade paperback, 2003. Original hardcover: Doubleday Crime Club, 1939. Pulp magazine reprint: Two Complete Detective Novels, Winter 1939-1940 (with The Cat Saw Murder, by D. B. Olsen). Hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1940.

Checking on www.abebooks.com just a few minutes ago, I found only one copy of the Crime Club edition for sale: Near Fine in a Near Fine jacket. Price: a mere $250.00. Further searching revealed a few other copies on other venues, one being a former library copy with no jacket. Price: a much more reasonable $35.00.

But if $14.95 is all you want to spend, this handsome trade paperback will do very nicely. This is but one of many classic mystery reprints coming from Tom & Enid Schantz of Rue Morgue Press, and they should be commended for a job well done, and for jobs yet to be done. (At the moment, the only other Clason title they’re published is The Man from Tibet, but perhaps others are on their way. Only sales will tell, I imagine.)

Only one thing is lacking, before I continue, and that is the original cover art, which as I recall was by Boris Artzybasheff. That gentleman no longer being available (or affordable) a fine piece of work by Rob Pudim was used in his stead. To my eye it’s a bit cluttered, but it Does Catch the Eye.

Clason’s series detective is an eminent Roman historian named Theocritus Lucius Westborough — Westborough for short — who also has earned a well-deserved reputation as a private investigator on the side. If this book is an example — which from my point of view it has to be, at least for the moment, since if I ever read an earlier book in the series, it was long ago and long forgotten — Westborough’s adventures are copiously filled with well-researched lore of ancient times, interspersed with mini-lectures on the same.

I’m jumping the gun here, but it’s Westborough’s knowledge of ancient history that helps crack a killer’s alibi — which is not quite fair to the reader not recently tutored in such matters — such as myself, I have to admit — but it’s a sizable step above nabbing a villain who reveals himself because he’s not aware that buildings do not have thirteenth floors, for example.

Just in passing: There is a deliberate misstatement on my part that is not quite correct in the last sentence of the previous paragraph, but if I were to speak more clearly, I would be revealing more of what Clason had up his sleeve than I should.

This, the seventh of ten cases Westborough is on record as having solved, takes place on an isolated island off the southern California shore, where first a valuable artifact is stolen — and Westborough called in — and then murder, when a missing butler is later found dead.

The owner of the island, a rich Greek businessman named Paphlagloss, is fascinated with the ancient Minoan culture, pre-historic Cretans whose civilization arose and fell even before the ancient Greeks, and his mansion is filled with valuable relics, artwork and jewels. Just the right place for skullduggery to be done, and with only a handful of suspects, one of whom is responsible for doing the dugging, it’s a perfect setting for a mystery.

Clason’s strength is in his characters and their dialogue. To my ears, the lengthy reports of letters and verbatim interviews of suspects are close to perfect. Other parts of the tale are excellent, while others, contrarily, are pure fuddle-muddle.

I like the following quote, for some reason, taken from pages 160-161. Paphlagloss’s daughter is having a private conversation with Westborough:

She shivered and drew the wrap closely to her slim body. “Why do things have to be in such a perfect devil of a mess?”

His mild eyes peered distressfully through his gold-rimmed spectacles. “The question, I should conjecture, has been propounded rather frequently during the four thousand years of recorded history. However, I am unable to recall a single instance where it was answered satisfactorily.”

“You are very wise!” she exclaimed.

He shrugged deprecatorily. “My wisdom is confined to a single fact. I have lived long enough to learn that most of my fellow creatures — and myself, as well — must of necessity be a little foolish.”

“What would you advise me to do?”

“I dare not advise you, my dear. The situation is too delicate. As delicate,” he added thoughtfully, “as the ripples of a Chinese nocturne.”

While it’s great to have this small gem of the Golden Age of Mysteries back again in print, I also have to suggest that it didn’t then, and it doesn’t now, have the staying power of one by a Queen, Christie, or a John Dickson Carr. Even so, and within its limitations, it is a gem in its own right, and no, they don’t write them like this anymore.

— January 2004

[UPDATE] 09-05-13. Checking on abebooks again just now, I found nine copies of the Crime Club edition for sale, ranging in price from $25 (bumped and frayed) to $300 (almost fine in jacket). Rue Morgue Press has a long informative profile of Clyde Clason, the author, and seven books in the Westborough series are now available from them. See below.

CLYDE B(urt) CLASON, 1903-1987.

The Death Angel (n.) Doubleday 1936. RM = Rue Morgue Press.

The Fifth Tumbler (n.) Doubleday 1936.

Blind Drifts (n.) Doubleday 1937. RM

The Purple Parrot (n.) Doubleday 1937. RM

The Man from Tibet (n.) Doubleday 1938.

The Whispering Ear (n.) Doubleday 1938.

Dragon’s Cave (n.) Doubleday 1939. RM

Murder Gone Minoan (n.) Doubleday 1939. RM

Poison Jasmine (n.) Doubleday 1940. RM

Green Shiver (n.) Doubleday 1941. RM