Sun 11 Dec 2011

ADVENTURES IN COLLECTING: Is Completism Fatal?, by Walker Martin.

Posted by Steve under Collecting , Columns , Magazines , Pulp Fiction[21] Comments

Is Completism Fatal?

by Walker Martin

Dear Walker:

My own collection is all but complete — meaning that I’ve almost acquired all of the items on my want list. Of course I’ll always be out there keeping my eye open for serendipitous books and magazines, but I only have a very few more such items that I’m actually looking for. Once I find those I’m essentially done. Then I’ll just give them all away to the Salvation Army thrift store and start over… Your advice, please!

Dear C.P.

You have touched on a dangerous subject that all serious collectors must beware. I’ve seen many collectors fall into the dreaded trap of completing their collection. Usually once the collection is completed then many collectors lose interest and start thinking what next?

This results in the selling off of many collections because the enthusiasm of the chase and the drive to collect is now finished. Collectors that limit themselves to a favorite author or magazine are prone to losing interest once their goal of completion has been achieved.

Since collecting can be so much fun, how do we avoid falling into the abyss and losing interest in our collections after completion? The answer I have found is very simple, you do not allow yourself to complete your collection. You have to keep expanding your interests.

For instance, in your case, if you are close to completing your SF wants, then you have to develop an interest in another genre, another subject, other magazines. Maybe detective fiction or adventure pulps or original art to go along with your SF collection. Something else!

For instance in my own case, I started off in 1956, at the age of 13 collecting SF. This continued for around 10 years until I discovered detective pulps thanks to Ron Goulart’s Hardboiled Dicks anthology. This led me to collecting all sorts of mystery fiction like Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Ross Macdonald. It led me to completing sets of such great magazines like Black Mask and Dime Detective.

But then around 1980, I was faced again with the horrifying realization that I was nearing completion of the detective and mystery wants. I quickly expanded to adventure and western fiction and started to work on extensive sets of Western Story, West, Short Stories, Adventure, All Story, Argosy, Blue Book, Popular, Sea Stories and many others.

As I started to complete these magazines and run out of reading matter, I decided my job was taking up too much of my time and interfering with my reading and collecting activities. So in 2000 I retired to concentrate on building up what may be the world’s largest collection of literary magazines.

I’ve yet to meet another collector that is interested in these artifacts, but I love them, and I can fall into a trance looking and smelling the scent of rows and rows of literary quarterlies like the Hudson Review, The Criterion, Scrutiny, The London Magazine, Kenyon Review, Paris Review, and The Virginia Quarterly. I could go on and on forever but I’m sure you are all disgusted and fatigued reading about someone else’s collecting addictions. Hell, I actually read these things.

But the end may be near, even for me. I’ve mentioned before about almost being crushed by the collapsing of one of my basement bookcases due to overloading. Then a year or so later several bookcases fell on top of me and my son. Then last month a bookcase of literary magazines showered me with more than a hundred issues of the Sewanee Review.

It was heavenly. I just stood there as the magazines rained down on me and I felt at peace. Then I had to go to work picking them up off the floor and stacking them before my wife came to investigate the noise. She’s heard the sound of collapsing shelves and stacks falling, so she never asked me until a couple days later about the crashing noise that she chose to ignore.

Probably, she was hoping that I had tempted fate once too often and had been pounded flat as a pancake by the old magazines that she now hates with a passion. But no, I survived once again, just like some pulp super hero!

So I say to you, C.P., don’t stop collecting. There are unknown fields still to conquer. Don’t spend all your salary on your bills, your family, college fees for your children. You work hard for your money; spend some of it on collecting!

Now I have to go back to a discussion I’ve been having with myself for 50 years. What is the greatest fiction magazine ever? Is it Adventure in the 1920’s, All Story in the teens, Black Mask and Weird Tales in the 1930’s, Astounding and Unknown in the 1940’s, Galaxy in the 1950’s and 1960’s?

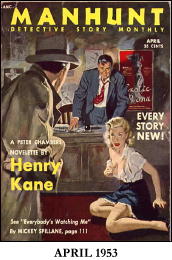

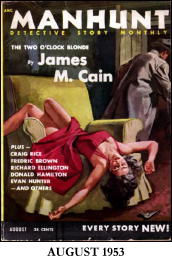

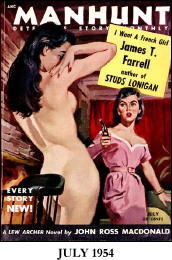

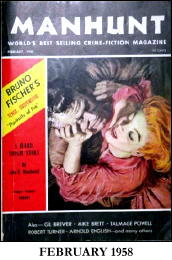

How about The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which has to fit somewhere. How about the SF fiction in Playboy and Omni, or the mystery fiction in Manhunt or EQMM?

Maybe I better fix up these bookcases so they don’t collapse; I need answers to the above questions!

Previously in this series: Collecting Manhunt.