Sun 31 Mar 2013

A Review by Doug Greene: GERALDINE BONNER – The Castlecourt Diamond Case.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[5] Comments

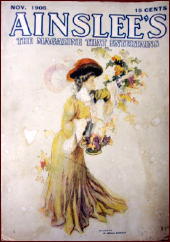

GERALDINE BONNER – The Castlecourt Diamond Case. Funk & Wagnalls, hardcover, 1906. (“Published, December, 1905.â€) First appeared in Ainslee’s Magazine, November 1905. Currently available in several different Print On Demand editions. Online edition: https://archive.org/details/castlecourtdiamond00bonnrich

This is the second version of this review, In the first, employing suitable modesty, I credited myself with the discovery of Geraldine Bonner, an entertaining but (or so I thought) entirely forgotten writer. Having stated that Bonner is unknown, I then belatedly checked my facts … and I found that five years ago Kathi Maio praised another book by Bonner, The Black Eagle Mystery (1916), in Murderess Ink.

Such are the perils of research.

Ms. Maio says that Black Eagle is “a charming mystery” — a phrase that also describes Castlecourt Diamond. The story of the theft of the Marchioness of Castlecourt’s diamonds is told in six “statements.” The first, by the Marchioness’ maid, describes the theft, introduces the main characters, and mentions the two detectives, one official, one private.

The second section is narrated by “Lilly Bingham, known in England as Laura Brice, in the United States as Frances Latimer, to the police of both countries as Laura the Lady.” It’s not much of a surprise that Laura stole the diamonds, though whether she was acting for someone else is not yet clear.

On the whole, however, the mystery is primarily a vehicle for Bonner to produce a comedy of manners, and the interest in the second part is Laura’s successful attempt to plant the diamonds on an unsuspecting American couple, Cassius and Daisy Kennedy. The Kennedys have been courting London society (they already know “a bishop and two lords”) and thus can’t throw out Laura and her henchman when, pretending an invitation, they arrive for dinner.

Two parts of the story are statements by the Kennedys, detailing their schemes to rid themselves of the diamonds and culminating in the theft of the jewels by a seeming sneak-thief. John Burns Gilsey, a private detective engaged by Lord Castlecourt, narrates a section that explains his deductions pointing to the Marchioness as the instigator of the plot, but the book concludes with a statement by the Marchioness showing that Gilsey was only partly correct.

The Castlecourt Diamond Case is indeed charming, and it is made even more so by its brevity — with large type and margins it contains less than 30,000 words, a far cry from many Victorian and Edwardian detective novels, as anyone who has labored through, say, Lawrence Lynch’s novels with their 550 godawful pages will testify.

I can’t claim to be the discoverer of Geraldine Bonner, but I’m happy to join Kathi Maio in recommending her works.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

GERALDINE BONNER (1870-1930). Born in Staten Island, N.Y.

The Castlecourt Diamond Case (n.) Funk 1906.

The Girl at Central (n.) Appleton 1915 [Molly Morganthau (Babbits)]

The Black Eagle Mystery (n.) Appleton 1916 [Molly Morganthau (Babbits).]

Miss Maitland, Private Secretary (n.) Appleton 1919 [Molly Morganthau (Babbits)]

The Leading Lady (n.) Bobbs 1926.

-Taken at the Flood (n.) Bobbs 1927.