Sat 14 Jan 2012

TV Review: THE FIRM (2012) [and] THE FUTURE OF TELEVISION, by Michael Shonk.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[18] Comments

[and] THE FUTURE OF TELEVISION

by Michael Shonk

THE FIRM. NBC, 08 January 2012. Two-hour pilot for TV series to air Thursday at 10pm (Eastern) beginning 12 January 2012. Based on the John Grisham novel. Cast: Josh Lucas as Mitch McDeere, Molly Parker as Abby McDeere. Created for TV by Lukas Reiter. Written by Lukas Reiter. Directed by David Straiton. Executive Produced by John Grisham, Lukas Reiter, John Morayniss, Noreen Halpern and Michael Rosenberg, Co-Executive Produced by Helen Shaver and Peter Noah.

It is 2012, ten years after the events of the film and novel.

We open with our hero, Mitch being chased. He is running towards the National Mall and the Lincoln Memorial. It is daytime. There is a crowd, yet no uniform security in sight. Our hero runs into a passing tour guide. They fall to the ground. Still no uniform security or police. We notice the large men in suits that are after Mitch. He runs and “They†chase. He runs through the reflecting pool.

I am bored. Hey, endless number of evil henchmen, some advice. Don’t bother trying to catch him when he is in an open space with many witnesses. Follow him until he is stupid enough to go to a place where there is limited ways of escape.

Extras, I know you are playing background, but this is 2012, don’t just ignore people running. No crowd today would let a well-dressed man run across the National Mall reflecting pool without having their cell phone cameras out. This entire chase and the faces of all would have gone viral on YouTube within an hour.

And where are the uniforms? This is post 9/11 in the middle of one of the heaviest trafficked parts of Washington D.C. and this chase, with a person run over, attracts no uniformed cops or security?

Back to the chase, Mitch thinks he has lost “Them.†He uses a pay phone to call his wife’s cell phone and warn her. A pay phone? Do those still exist? I know he does not use his cell phone because “They†can trace where he is through the cell phone. (I watch Person of Interest.) But our hero and wife have a plan, a plan that did not consider disposable untraceable cell phones. (Have they never seen an episode of Burn Notice?)

Next he goes to talk to the one person who knows the truth. Where does Mitch pick as a safe place to meet? In a high-rise hotel room with only two exits, the apartment door and the window leading to the patio several floors above the ground. (Get him now henchmen, get him now.)

The “Person Who Knows the Truth†refuses to share what he knows because “They†will kill him and he doesn’t want to die. Someone knocks on the door. So the “Person Who Knows the Truth†commits suicide by jumping off the room’s patio.

I understand the scene is meant to introduce the characters and action, but flip the settings. Have Mitch running in the hotel hallways and stairways, “They†chase. He escapes. Call wife on disposable cell phone. He meets the “Person Who Knows the Truth†in the National Mall. Terrified, the “Person Who Knows the Truth†is spooked. He runs and is hit and killed by a car. Mindless TV action can be entertaining without insulting your intelligence.

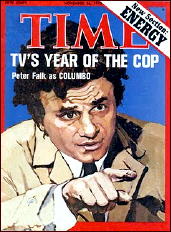

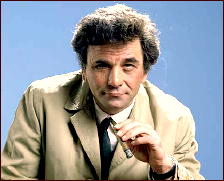

The show has been on for less than five minutes. At this point, I had to make a serious choice… continue and waste two hours of my life I’d never get back or watch something else. I went to my Amazon Video Library and watched They Call It Murder (1971).

This got me to thinking about how the TV show has moved beyond the TV. You don’t need a TV to watch The Firm pilot movie or the weekly series. Visit the official website at http://www.nbc.com/the-firm/.

At any point in the day you can watch a DVD featuring the first PI to appear on network TV (Martin Kane, Private Eye; NBC, 1949), or you can watch on your favorite device that streams or downloads video the very latest TV network PI (The Finder; Fox 2012).

Today we have countless choices on countless platforms all available for us on demand and most are mobile. Any second we feel bored, virtually anywhere, we can pull out our favorite handheld device and watch a TV show.

Will this change how television stories are told? Can you tell a story that visually works as well on a tablet as on a big screen TV? Will viewers care?

Will we watch different types of TV shows on our tablet than at home? Will we continue to sit in front of the TV screen and mindlessly watch whatever is on or will we choose the television show as well as when we mindlessly watch it on our preferred device?

So what began as a review of a badly written TV thriller ends with questions about how will we watch television in the future. Maybe if I had been more patient I would have found The Firm an entertaining thriller.

Who cares, I was bored and had better things to do. With more choices and easier access we have a better chance to find the exact fit for our leisure time needs of the moment. Television will no longer be for the mass audience but instead for each individual viewer. How will television deal with that?